Medicaid spending in Kentucky

This page covering Medicaid spending by state last received a comprehensive update in 2017. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia. Please contact us with any updates.

![]() This article does not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

This article does not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

| Medicaid spending in Kentucky | ||||||

| Overview | ||||||

| Number of enrollees: 1,246,3491 | ||||||

| Total spending: $9.66 billion3 | ||||||

| Spending per enrollee: $7,2794 | ||||||

| Percent of state budget: 30.9%4 | ||||||

| Medicaid eligibility limit: 195% FPL3 | ||||||

| Expansion?: Yes2 | ||||||

| CHIP spending: $222 million4 | ||||||

| CHIP eligibility limit: 218% FPL2 | ||||||

Data years

| ||||||

| Medicaid spending in the U.S. • Medicare • Medicaid • Obamacare overview | ||||||

Kentucky's Medicaid program provides medical insurance to groups of low-income people and individuals with disabilities. Medicaid is a nationwide program jointly funded by the federal government and the states. Medicaid eligibility, benefits, and administration are managed by the states within federal guidelines. A program related to Medicaid is the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which covers low-income children above the poverty line and is sometimes operated in conjunction with a state's Medicaid program. Medicaid is a separate program from Medicare, which provides health coverage for the elderly.

This page provides information about Medicaid in Kentucky, including eligibility limits, total spending and spending details, and CHIP. Each section provides a general overview before detailing the state-specific data.

Background

Established in 1965, Medicaid is the primary source of health insurance coverage for low-income and disabled individuals and the largest source of financing for the healthcare services they need. In 2014, about 80 million individuals were enrolled in Medicaid, or 25.9 percent of the total United States population. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid accounted for one-sixth of healthcare spending in the United States during that year.[5][6][7]

The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) monitors state Medicaid programs and establishes requirements for service delivery, quality, funding, and eligibility standards. Medicaid does not provide healthcare directly. Instead, it pays hospitals, physicians, nursing homes, health plans, and other healthcare providers for covered services that they deliver to eligible patients.[7][8]

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, also known as Obamacare, provided for the expansion of Medicaid to cover all individuals earning incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, which amounted to $16,643 for individuals and $33,948 for a family of four in 2017. A 2012 United States Supreme Court decision made the Medicaid expansion voluntary on the part of the states.[9][10]

Eligibility

Eligibility for each state's Medicaid program is subject to minimum federal standards, both in the population groups states must cover and the maximum amount of income enrollees can make. States are required to cover the following population groups and income levels:[10][11]

- states must cover pregnant women up to at least 138 percent of the federal poverty level ($16,643 for an individual, $33,948 for a family of four in 2017)

- states must cover preschool-age children up to at least 138 percent of the federal poverty level ($16,643 for an individual, $33,948 for a family of four in 2017)

- states must cover school-age children up to at least 100 percent of the federal poverty level ($12,060 for an individual, $24,600 for a family of four in 2017)

- states must cover elderly and disabled individuals up to at least 75 percent of the federal poverty level ($9,045 for an individual, $18,450 for a family of four in 2017)

- states must cover working parents up to at least 28 percent of the federal poverty level ($3,376 for an individual, $6,888 for a family of four in 2017)

The Affordable Care Act authorized states to expand their Medicaid programs to offer coverage to childless adults up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, though they were not required to do so. As of November 2018, a total of 36 states and Washington, D.C., had expanded or voted to expand their Medicaid programs.Kentucky opted to fully expand its Medicaid program, covering childless adults earning incomes up to 138 percent FPL. Full details on Medicaid eligibility for Kentucky and three of its neighboring states are provided in the table below.[12]

| Medicaid eligibility by population category, 2016 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Children | Pregnant women | Adults | ||||||||

| Medicaid ages 0-1 | Medicaid ages 1-5 | Medicaid ages 6-18 | Separate CHIP | Medicaid | CHIP | Parent | Childless adults | ||||

| Kentucky | 195% | 159% | 159% | 213% | 195% | N/A | 23% | 138% | |||

| Tennessee | 195% | 142% | 133% | 250% | 195% | N/A | 103% | No | |||

| Virginia | 143% | 143% | 143% | 200% | 143% | 200% | 49% | No | |||

| West Virginia | 158% | 141% | 133% | 300% | 158% | N/A | 19% | 138% | |||

| Note: Figures represent household income as a percentage of the federal poverty level. | |||||||||||

Expansion under the Affordable Care Act

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provided for the expansion of Medicaid to cover childless adults whose income is 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) or below. The provision for expanding Medicaid went into effect nationwide in 2014. As of November 2018, a total of 36 states and Washington, D.C., had expanded or voted to expand Medicaid.

Kentucky expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act in 2013. Then-Governor Steve Beshear (D) supported the expansion, stating in 2013 that it was "the single-most important decision in our lifetime for improving the health of Kentuckians." As a candidate, Governor Matt Bevin (R) criticized the Medicaid expansion, saying, "We cannot afford to keep enrolling people at 138 percent." In August 2016, Bevin asked the federal government to approve changes to the program, including requiring premiums, co-pays, and community involvement for enrollees. On January 12, 2018, the federal government approved Kentucky's request for a waiver, allowing it to implement changes to the Medicaid program, including community involvement rules requiring that enrollees spend 80 hours per month working, volunteering, or in job training. This made Kentucky the first state in the nation impose such requirements. On January 24, 2018, 15 Kentucky residents filed a class action lawsuit against the federal government. In their complaint, filed in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, attorneys for the plaintiffs wrote the following:[1][2][3][4][13][14]

| “ | This case challenges the efforts of the Executive Branch to bypass the legislative process and act unilaterally to 'comprehensively transform' Medicaid, the cornerstone of the social safety net. Purporting to invoke a narrow statutory waiver authority that allows experimental projects 'likely to assist in promoting the objectives' of Medicaid, the Executive Branch has instead effectively rewritten the statute, bypassing congressional restrictions, overturning a half century of administrative practice, and threatening irreparable harm to the health and welfare of the poorest and most vulnerable in our country.[15] | ” |

On January 25, Bevin released the following statement in response to the lawsuit:[16]

| “ | We expected this legal challenge because this is what liberals do. They run to the courts in their perverse efforts to keep good people dependent on government programs. The people of Kentucky deserve better than to be financially enslaved by such dependence, and I have absolute confidence that the waiver will prevail against this baseless challenge. Many months of diligent collaboration between our team, CMS, HHS and the Trump Administration have resulted in a rock solid demonstration waiver. We know that we stand on a strong legal foundation. Kentucky now has an opportunity to prove to our citizens and to those in other states that the waiver will work and that all of Kentucky and America will be better for it.[15] | ” |

Support

Arguing in support of the expansion of Medicaid eligibility, the Center for American Progress states that the expansion helps increase the number of people with health insurance and benefits states economically. The organization argues that by providing health insurance to those who would otherwise be uninsured, Medicaid expansion allows low-income families to spend more money on food and housing:[17]

| “ | Medicaid coverage translates into financial flexibility for families and individuals, allowing limited dollars to be spent on basic needs, including breakfast for the majority of the month or a new pair of shoes for a job interview.[15] | ” |

| —Center for American Progress | ||

Regarding financial costs for states, the organization argues that "states that expand their Medicaid coverage will not incur unsustainable costs," citing a Congressional Budget Office report that estimated an increase in spending of 2.8 percent. The organization also argues that states will offset these costs with increased revenues and other financial gains:

| “ | Sources of increased revenues include state sales taxes, insurance taxes, and prescription-drug rebates. States will also incur savings, as the federal government will be paying a much higher share of the cost for populations that were previously ineligible and therefore solely paid for by states. This will free up billions of dollars from state budgets.[15] | ” |

| —Center for American Progress | ||

Marilyn Tavenner, President and CEO of the health insurance trade association America's Health Insurance Plans, also spoke in support of Medicaid expansion in September 2016, saying she would like to see all states expand the program. "Medicaid is going to become the bigger issue [from the] affordability perspective," Tavenner said, arguing that Medicaid expansion would pressure the country to address rising health costs.[18]

Opposition

Arguing against Medicaid expansion in a February 2014 article, Michael Tanner, a fellow at the Cato Institute, states that Medicaid expansion is costly for states and does not provide better access to healthcare for low income individuals. Tanner argues that although states are required to pay at most 10 percent of costs for enrollees who became eligible under expanded programs, this still represents a significant cost increase for states. Tanner also argues that states will see greater costs than predicted as previously unenrolled individuals discover they are eligible under the traditional eligibility limits.[19]

Regarding healthcare access, Tanner cites a study from the Oregon Health Insurance Exchange, which "concluded that 'Medicaid coverage generated no significant improvements in measured physical-health outcomes.'" Tanner also states that "Other studies show that, in some cases, Medicaid patients actually wait longer and receive worse care than the uninsured." Tanner argues that this is due to Medicaid's level of reimbursement to doctors:[19]

| “ | While Medicaid costs taxpayers a lot of money, it pays doctors little. On average, Medicaid reimburses doctors only 72 cents out of each dollar of costs. As a result, many doctors limit the number of Medicaid patients they serve or refuse to take them at all.[15] | ” |

| —Michael Tanner | ||

The National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) also advocated against Medicaid expansion in February 2017, arguing that the federal government may not always agree to cover 90 percent of the costs:[20]

| “ | Our small business members have looked at this issue from every perspective and believe expanding an underfunded, cumbersome, and poorly administered program like Medicaid would be irresponsible. The bottom line is this: Does anyone really believe that Washington will continue to pick up 90 percent of new costs after 2020?[15] | ” |

| —Gregg Thompson, state director of the North Carolina NFIB chapter | ||

Benefits

In large part, the states "determine the type, amount, duration, and scope" of benefits offered to individuals enrolled in Medicaid, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. However, benefits are subject to federal minimum standards. The federal government has outlined 16 benefits that are required of all Medicaid programs:[21][22][23]

- Hospital services for inpatients

- Hospital services for outpatients

- Health screenings for individuals and children under age 21

- Nursing facility care

- Home healthcare

- Physician checkups and other services

- Rural health clinic visits

- Visits to federally qualified health centers

- Laboratory tests and X-rays

- Family planning

- Nurse midwife care

- Maternity and newborn care

- Visits to pediatric and family nurse practitioners

- Visits to licensed freestanding birth centers

- Emergency and non-emergency medical transportation

- Tobacco cessation programs for pregnant women

In addition, the Affordable Care Act required that all Medicaid enrollees who became eligible under expanded programs receive coverage for prescription drugs, substance abuse treatment, and mental health treatment. Beyond the required benefits, there are several other optional benefits states may choose to offer enrollees, such as dental care and physical therapy. Other services may be offered with approval from the secretary of the United States Department of Health and Human Services. Benefits offered may not differ from person to person due to diagnoses or condition of health.[21][23][24]

Optional benefits offered in Kentucky

According to the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, as of 2017, the optional benefits included in the bulleted list below were offered in Kentucky. Note that other, less common specialized services may also be offered, such as nutrition services and acupuncture. For more complete information on Medicaid benefits, links to state Medicaid offices can be found here.[23][25]

- Freestanding ambulatory surgery centers

- Public and mental health clinics

- Mental health and substance abuse treatment

- Certified registered nurse anesthetists

- Chiropractic care

- Dental care

- Dental surgery

- Optometrists

- Podiatrists

- Prescription drugs

- Home medical equipment

- Prosthetics

- Adult health screenings

- Case management

- Home and community-based services

- Hospice care

- Inpatient psychiatric care for individuals under age 21

- Inpatient care for mental diseases for individuals age 65+

- Intermediate care for intellectual disabilities

State and federal spending

Total spending

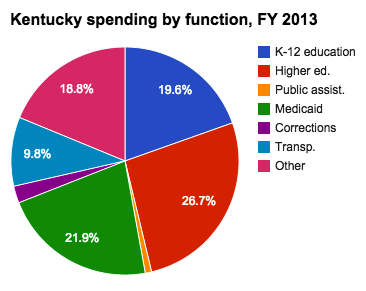

During fiscal year 2016, Medicaid spending nationwide amounted to nearly $553.5 billion. Spending per enrollee amounted to $7,067 in fiscal year 2013, the most recent year for which per-enrollee figures were available as of June 2017. Total Medicaid spending grew by 33 percent between fiscal years 2012 and 2016. The Medicaid program is jointly funded by the federal and state governments, and at least 50 percent of each state's Medicaid funding is matched by the federal government, although the exact percentage varies by state. Medicaid is the largest source of federal funding that states receive. Changes in Medicaid enrollment and the cost of healthcare can impact state budgets. For instance, in Kentucky, the percentage of the state's budget dedicated to Medicaid rose from 21.9 percent in 2010 to 30.9 percent in 2015. However, state cuts to Medicaid funding can also mean fewer federal dollars received by the state.[26][27][28]

During fiscal year 2016, combined federal and state spending for Medicaid in Kentucky totaled about $9.66 billion. Spending on Kentucky's Medicaid program increased by about 69.5 percent between fiscal years 2012 and 2016. Hover over the points on the line graph below to view Medicaid spending figures for Kentucky. Click [show] on the red bar below the graph to view these figures as compared with three of Kentucky's neighboring states.[29][30][31][32][33]

| Total Medicaid spending, fiscal years 2012 - 2016 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Percentage change |

| Kentucky | $5,701,684,085 | $5,822,414,805 | $7,907,494,806 | $9,423,467,372 | $9,664,001,530 | 69.49% |

| Tennessee | $8,797,895,567 | $8,716,487,022 | $9,263,093,195 | $9,094,051,961 | $9,517,026,811 | 8.17% |

| Virginia | $6,906,432,609 | $7,291,109,038 | $7,611,531,956 | $8,032,760,161 | $8,564,487,079 | 24.01% |

| West Virginia | $2,789,587,443 | $3,024,226,160 | $3,349,005,677 | $3,646,548,197 | $3,693,853,210 | 32.42% |

| United States | $415,154,234,831 | $438,233,172,298 | $475,910,000,000 | $523,709,237,879 | $553,453,647,756 | 33.31% |

| Note: Expenditures include both state and federal expenditures. Expenditures do not include administrative costs. Percentages calculated by Ballotpedia. | ||||||

Spending details

In 2013, the most recent year per enrollee spending figures were available as of June 2017, spending per enrollee in Kentucky amounted to $7,279. Total enrollment in 2017 amounted to 1.25 million individuals. Total federal and state Medicaid spending for Kentucky during 2016 amounted to about $9.66 billion. The federal government paid 65.6 percent of these costs, while the state paid the remaining 34.4 percent. Medicaid accounted for 30.9 percent of Kentucky's budget in 2015.[34][35][36][37][38]

| Medicaid spending details | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Total spending (2016) | Enrollment (March 2017) | Per enrollee spending (2013) | FMAP percentage (2018)* | Federal share (2016) | State share (2016) | Percent of state budget (2015) |

| Kentucky | $9,664,001,530 | 1,246,349 | $7,279 | 71.17% | 78.7% | 21.3% | 30.9% |

| Tennessee | $9,517,026,811 | 1,552,167 | $5,771 | 65.82% | 65.6% | 34.4% | 32.6% |

| Virginia | $8,564,487,079 | 991,571 | $7,603 | 50.00% | 50.2% | 49.8% | 17.5% |

| West Virginia | $3,693,853,210 | 564,408 | $8,332 | 73.24% | 77.7% | 22.3% | 22.1% |

| United States | $553,453,647,756 | 74,600,261 | $7,067 | 50.00% | 63.0% | 37.0% | 28.2% |

| Note: FMAP stands for Federal Medical Assistance Percentage and represents the percentage of state Medicaid spending that is eligible for federal matching funds. | |||||||

Medicaid spending can generally be broken up into the following categories:

- Acute care services are those that are typically provided within a short time frame, such as inpatient hospital stays, lab tests, and prescription drugs.

- Long-term care services are those provided over a long period of time, such as home care and mental health treatment.

- Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments are funds given to hospitals that tend to serve more low-income and uninsured patients than other hospitals.

- Payments to Medicare include covering Medicare premiums for individuals who are dually eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare.

- FFS refers to fee-for-service payments, in which doctors are reimbursed for each test and service performed.

- Managed care is the practice of paying private health plans with Medicaid funds to cover enrollees.

The largest portion—65 percent—of Medicaid spending in Kentucky in 2016 went to managed care. The next-largest portion of Medicaid spending in Kentucky went to FFS long-term care, which comprised about 20 percent of spending. About 3 percent of Medicaid spending in Kentucky was used for payments to Medicare. Hover over the sections in the column chart below to view more data points for Kentucky and three of its neighboring states.[39]

| Back to top↑ |

Children's Health Insurance Program

The Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) is a public healthcare program for low-income children who are ineligible for Medicaid. CHIP and Medicaid are related programs, and the former builds on Medicaid's coverage of children. States may run CHIP as an extension of Medicaid, as a separate program, or as a combination of both. Like Medicaid, CHIP is financed by both the states and the federal government, and states retain general flexibility in the administration of its benefits.[40]

CHIP is available specifically for children whose families make too much to qualify for Medicaid, meaning they must earn incomes above 138 percent of the federal poverty level, or $33,948 for a family of four in 2017. Upper income limits for eligibility for CHIP vary by state, from 175 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) in North Dakota to 405 percent of the FPL in New York. States have greater flexibility in designing their CHIP programs than with Medicaid. For instance, fewer benefits are required to be covered under CHIP. States can also charge a monthly premium and require cost sharing, such as copayments, for some services; the total cost of premiums and cost sharing may be no more than 5 percent of a family's annual income. As of January 2017, 14 states charged only premiums to CHIP enrollees, while nine states required only cost sharing. Sixteen states required both premiums and cost sharing. Eleven states did not require either premiums or cost sharing.[10][40][41][42][43]

As of 2017, Kentucky served CHIP enrollees through a combination of Medicaid and a separate program. Its upper eligibility limit was 218 percent of the FPL, meaning a family of four had to make less than $53,628 per year to qualify. The state imposed cost sharing beginning at 143 percent of the FPL. Below is a table with some general information about CHIP in Kentucky, including spending figures, the state's federal match percentage, and enrollment in the program. These data points are compared with those of its neighboring states.[44][45][46][47][48]

| General CHIP information for Kentucky | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Total CHIP expenditures, 2015 (millions) | Enhanced FMAP, 2017* | CHIP enrollment, 2014 | Program type | |||

| Federal | State | Total | |||||

| Kentucky | $174.80 | $47.20 | $222.00 | 100.00% | 61,473 | Combination | |

| Tennessee | $155.10 | $50.40 | $205.50 | 98.47% | 112,826 | Combination | |

| Virginia | $187.00 | $100.70 | $287.70 | 88.00% | 186,513 | Combination | |

| West Virginia | $49.70 | $12.50 | $62.10 | 100.00% | 40,864 | Separate CHIP | |

| United States | $9,528.00 | $3,933.40 | $13,461.40 | 88.00% | 8,129,426 | N/A | |

| * FMAP stands for Federal Medical Assistance Percentage and reflects the percentage of state dollars spent on CHIP that are eligible for matching funds from the federal government. | |||||||

| Back to top↑ |

Historical data

Enrollment

To view detailed historical data on Medicaid enrollment in Kentucky for 2010, click "Show more" below to expand the section.

According to a July 2014 report from the Pew Charitable Trusts, in 2010 there were 919,864 Kentucky residents enrolled in Medicaid. The majority of spending, 63 percent, was on the elderly and disabled, who made up 36 percent of Medicaid enrollees. This was typical of most states, since this group of enrollees is "more likely to have complex health care needs that require costly acute and long-term care services," according to the Pew Charitable Trusts. The portion of Medicaid enrollees who are elderly and disabled is a factor taken under significant consideration when state lawmakers make appropriations for the program each year.[49]

| Distribution of Medicaid enrollment and payments, 2010 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Enrollment rates | Payment for services | ||||

| Total | Elderly and disabled individuals | Parents and children | Total (in billions) | Elderly and disabled individuals | Parents and children | |

| Kentucky | 919,864 | 36% | 64% | $5.5 | 63% | 37% |

| Tennessee | 1,509,354 | 28% | 72% | $8.4 | 53% | 47% |

| Virginia | 1,027,075 | 28% | 72% | $6.1 | 64% | 36% |

| West Virginia | 416,858 | 38% | 62% | $2.5 | 72% | 28% |

| United States | 66,390,642 | 24% | 76% | $369.3 | 64% | 36% |

| Source: The Pew Charitable Trusts, "State Health Care Spending on Medicaid" | ||||||

Dual eligibility

- See also: Medicaid and Medicare dual eligibility

To view detailed historical data on dual eligibility for Medicaid and Medicare in Kentucky for 2011, click "Show more" below to expand the section.

Enrollment

Some individuals, such as low-income seniors, are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid; these individuals are known as dual-eligible beneficiaries. For those enrolled in Medicare who are eligible, enrolling in Medicaid may provide some benefits not covered by Medicare, such as stays longer than 100 days at nursing facilities, prescription drugs, eyeglasses, and hearing aids. Medicaid may also be used to help pay for Medicare premiums. According to the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, in 2011 there were 194,100 dual eligibles in Kentucky, or 20 percent of Medicaid enrollees. While average Medicaid spending per enrollee was $5,937, spending per dual eligible was $10,770.[50][51][52][53][54]

| Dual eligible enrollment, fiscal year 2011 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Total Medicaid enrollment* | Medicaid spending per enrollee | Number of dual eligibles | Dual eligibles as a percent of Medicaid enrollees | Medicaid spending per dual eligible | ||

| Kentucky | 796,500 | $5,937 | 194,100 | 20% | $10,770 | ||

| Tennessee | 1,324,700 | $5,155 | 279,100 | 18% | $10,600 | ||

| Virginia | 820,700 | $6,224 | 191,700 | 18% | $13,938 | ||

| West Virginia | 335,600 | $6,315 | 87,200 | 20% | $13,796 | ||

| United States | 53,535,000 | $5,790 | 9,972,300 | 15% | $16,904 | ||

| * Data on Medicaid enrollment figures may differ depending on the source of data and the computational methods used, such as "point-in-time" figures versus "ever-enrolled" figures. Source: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "State Health Facts" | |||||||

Spending

Total Medicaid spending for dual eligibles in Kentucky amounted to $1.8 billion in 2011. Most payments were made toward long-term care.[55]

| Medicaid spending for dual eligibles by service, fiscal year 2011 (in millions) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Medicare premiums | Acute care | Prescribed drugs | Long-term care | Total | |

| Kentucky | $212 | $325 | $40 | $1,241 | $1,817 | |

| Tennessee | $335 | $1,565 | $18 | $663 | $2,582 | |

| Virginia | $223 | $387 | $16 | $1,700 | $2,325 | |

| West Virginia | $107 | $107 | $12 | $812 | $1,037 | |

| United States | $13,489 | $40,190 | $1,462 | $91,765 | $146,906 | |

| Source: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "State Health Facts" | ||||||

| Back to top↑ |

Noteworthy events

2018

On June 29, 2018, a federal judge barred implementation of a series of changes to Kentucky's Medicaid program, including the imposition of work or community engagement requirements for Medicaid recipients.[56] Judge James Boasberg, of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, found that the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) had failed to consider whether the changes (referred to as the Kentucky HEALTH plan) "would in fact help the state furnish medical assistance to its citizens, the central objective of Medicaid." Boasberg rescinded approval of the program, which had been granted by HHS on January 12, 2018, and ordered the department to review the matter further.[57]

Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, issued the following statement in response to the ruling: "Today’s decision is disappointing. States are the laboratories of democracy and numerous administrations have looked to them to develop and test reforms that have advanced the objectives of the Medicaid program. The Trump Administration is no different. We are conferring with the Department of Justice to chart a path forward."[58]

Elizabeth Lower-Basch, director of income and work supports at the Center for Law and Social Policy, praised the ruling: "The court made the right decision. It found that HHS did not even consider the basic question of whether [Kentucky's program] would harm the core Medicaid goal of providing health coverage, and it prohibits Kentucky from implementing it until HHS makes such an assessment."[59]

On July 1, 2018, the administration of Governor Matt Bevin (R) announced via email that dental and vision benefits for approximately 460,000 Medicaid recipients would end effective July 1. "When Kentucky HEALTH was struck down by the court, the 'My Rewards Account' program [i.e., the program, established by the Kentucky HEALTH plan, under which Medicaid expansion recipients paid for dental and vision coverage] was invalidated, meaning there is no longer a legal mechanism in place to pay for dental and vision coverage for about 460,000 beneficiaries [covered under Medicaid expansion] ... As such, they no longer have access to dental and vision coverage as a result of the court's ruling." This did not apply to traditional Medicaid recipients, such as pregnant women, children, and the disabled. Rep. John Yarmuth (D-Ky.) criticized the action and announced that his office was seeking an opinion from the Centers for Medicaid and Medicaid Services (CMS) on its legality: "We don't think [Bevin] can do that. We checked with CMS — they said they don't know if he can do that."[60]

On March 27, 2019, Boasberg]] again blocked implementation of Kentucky's community engagement requirements, finding that changes made to the program since he first ruled on it in 2018 were not sufficient to remedy the issues outlined in the case.[61]

Recent news

The link below is to the most recent stories in a Google news search for the terms Medicaid Kentucky. These results are automatically generated from Google. Ballotpedia does not curate or endorse these articles.

See also

Medicaid in the 50 states

Click on a state below to read more about the Medicaid program in that state.

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 National Academy for State Health Policy, "Where States Stand on Medicaid Expansion Decisions," accessed June 28, 2017

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Commonwealth of Kentucky, "Governor Steve Beshear's Communications Office," May 9, 2013

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Louisville Business First, "Bevin: Big changes could be coming to Medicaid in 2017," December 30, 2015

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lexington Herald-Leader, "Gov. Bevin submits Medicaid overhaul plan to Feds, with some changes," August 24, 2016

- ↑ The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, "Medicaid Enrollment in 50 States," February 2010 (Note 1)

- ↑ Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, "Policy Basics: Introduction to Medicaid," June 19, 2015

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Medicaid Financing: How Does it Work and What are the Implications?" May 20, 2015

- ↑ Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- ↑ Kaiser Health News, "Consumer’s Guide to Health Reform," April 13, 2010

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Office of The Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, "Poverty Guidelines," accessed June 9, 2017

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Federal Core Requirements and State Policy Options in medicaid: Current Policies and Key Issues," accessed May 13, 2017

- ↑ Medicaid.gov, "Medicaid & CHIP in Kentucky," accessed May 13, 2017

- ↑ United States District Court for the District of Columbia, "Stewart v: Hargan: Class Action Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief," January 24, 2018

- ↑ The Washington Post, "Kentucky becomes the first state allowed to impose Medicaid work requirement," January 12, 2018

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ The Courier-Journal, "Trump lacks the authority to change Kentucky's Medicaid law, lawsuit says," January 26, 2018

- ↑ Center for American Progress, "10 Frequently Asked Questions About Medicaid Expansion," April 2, 2013

- ↑ Bloomberg BMA, "Medicaid Expansion Will Drive Affordability, Insurance Leader Says," September 29, 2016

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Cato Institute, "No Miracle in Medicaid Expansion," February 4, 2014

- ↑ National Federation of Independent Business, "NFIB Calls for Halt on Last-Minute Medicaid Expansion Attempt," February 1, 2017

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Medicaid.gov, "Benefits," accessed June 8, 2017

- ↑ The Commonwealth Fund, "Medicaid Benefit Designs for Newly Eligible Adults: State Approaches," May 11, 2015

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "KCMU Medicaid Benefits Database: General Benefits and Cost-Sharing Notes," January 2014

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Medicaid Benefits Data Collection," accessed September 24, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Medicaid Benefits Data Collection," accessed September 24, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Total Medicaid Spending," accessed July 17, 2015

- ↑ Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, "Medicaid Benefit Spending per Full-Year Equivalent Enrollee by State and Eligibility Group, FY 2012," accessed September 14, 2015

- ↑ The Pew Charitable Trusts, "State Health Care Spending on Medicaid: Table B.1," accessed July 17, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Total Medicaid Spending - 2012," accessed July 17, 2015

- ↑ Kaiser Family Foundation, "Total Medicaid Spending - 2013," accessed May 31, 2017

- ↑ Kaiser Family Foundation, "Total Medicaid Spending - 2014," accessed May 31, 2017

- ↑ MACPAC, "Medicaid Spending by State, Category, and Source of Funds," accessed May 31, 2017

- ↑ Kaiser Family Foundation, "Total Medicaid Spending - 2016," accessed May 31, 2017

- ↑ MACPAC, "Medicaid Benefit Spending Per Full-Year Equivalent (FYE) Enrollee by State and Eligibility Group," accessed May 26, 2017

- ↑ MACPAC, "Medicaid as a Share of State Budgets Including and Excluding Federal Funds by State," accessed May 26, 2017

- ↑ Kaiser Family Foundation, "Federal and State Share of Medicaid Spending," accessed May 26, 2017

- ↑ Kaiser Family Foundation, "Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid and Multiplier," accessed May 26, 2017

- ↑ Medicaid.gov, "March 2017 Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights," accessed May 26, 2017

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Distribution of Medicaid Spending by Service," accessed May 31, 2017

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Children’s Health Coverage: Medicaid, CHIP and the ACA," March 26, 2014

- ↑ Healthcare.gov, "The Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP)," accessed March 24, 2016

- ↑ National Health Law Program, "Q & A: The Supreme Court's Decision on the ACA's Medicaid Expansion," July 23, 2016

- ↑ Kaiser Family Foundation, "Premium, Enrollment Fee, and Cost Sharing Requirements for Children, January 2017," accessed June 9, 2017

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2017: Findings from a 50-State Survey," accessed May 31, 2017

- ↑ Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, "CHIP Spending by State," accessed May 26, 2016

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for CHIP," accessed May 26, 2016

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "CHIP Program Name and Type," accessed May 26, 2016

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Total Number of Children Ever Enrolled in CHIP Annually," accessed May 26, 2017

- ↑ The Pew Charitable Trusts, "State Health Care Spending on Medicaid," July 2014

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Monthly Medicaid Enrollment (in thousands)," accessed September 4, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Medicaid Spending per Enrollee (Full or Partial Benefit)," accessed September 4, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Number of Dual Eligible Beneficiaries," accessed September 4, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Dual Eligibles as a Percent of Total Medicaid Beneficiaries," accessed September 4, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Medicaid Spending per Dual Eligible per Year," accessed September 4, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Distribution of Medicaid Spending for Dual Eligibles by Service (in Millions)," accessed July 17, 2015

- ↑ Under the program, recipients would be required to complete at least 80 hours per month of work, job training, or qualified community service.

- ↑ United States District Court for the District of Columbia, "Stewart v. Azar: Memorandum Opinion," June 29, 2018

- ↑ Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, "Administrator Verma Statement: Federal District Court Decision on Kentucky Medicaid Program," June 29, 2018

- ↑ NPR, "Federal Judge Blocks Medicaid Work Requirements In Kentucky," June 29, 2018

- ↑ Louisville Courier Journal, "Bevin cuts dental, vision benefits to nearly 500K Medicaid recipients," July 2, 2018

- ↑ United States District Court for the District of Columbia, "Gresham v. Azar: Memorandum Opinion," March 27, 2019