Your feedback ensures we stay focused on the facts that matter to you most—take our survey

United Steelworkers v. Weber

United Steelworkers v. Weber is a case decided by the United States Supreme Court in 1979. It held that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 did not prohibit employers from favoring women and minorities, and that it did not prohibit all forms of affirmative action programs.[1][2]

Background

Brian Weber was employed as a laboratory assistant at a chemical plant owned by Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Corp. Kaiser had, as part of a collective agreement with the United Steelworkers of America, implemented an affirmative action program within their training program; half the positions in the program were reserved for black employees, even though the company had more white employees. Weber, a white employee, applied for the program and was passed over for a position as none were available for him. Weber sued the company in 1974, arguing this was illegal racial discrimination that violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. Kaiser and United Steelworkers argued they were using this affirmative action program to remedy historical discrimination. In 1997, the district court held that the program was in violation of Title VII. United Steelworkers appealed, and the appeals court affirmed the lower court decision in 1978, finding that all employment preferences based upon race violated Title VII's prohibition against racial discrimination in employment. The union appealed to the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case in March, 1979.[1][2][3]

Decision

On June 27, 1979, in a 5-2 decision, the Supreme Court found in favor of the union (two Justices abstained). The court held that the training program did not violate Title VII , because the Civil Rights Act did not prohibit private institutions from taking steps to implement the goals of Title VII. The court found that since the training program sought to eliminate the pattern of racial segregation and discrimination in employment but did not expressly prohibit white employees from advancing in the company, it was consistent with the intent of Title VII. The majority opinion was delivered by Justice William Brennan and joined by Justices Potter Stewart, Byron White, Thurgood Marshall, and Harry Blackmun. [1][2][4]

Justice Brennan wrote the following in the majority opinion:[4]

| “ | We need not today define in detail the line of demarcation between permissible and impermissible affirmative action plans. It suffices to hold that the challenged Kaiser-USWA affirmative action plan falls on the permissible side of the line. The purposes of the plan mirror those of the statute. Both were designed to break down old patterns of racial segregation and hierarchy. Both were structured to "open employment opportunities for Negroes in occupations which have been traditionally closed to them."[5] | ” |

| —Justice William Brennan | ||

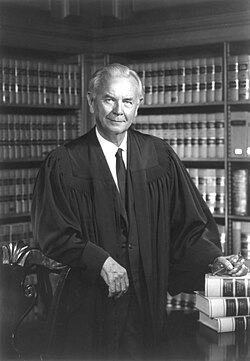

Chief Justice Warren Burger and Justice William Rehnquist dissented. The dissent argued that the program was in violation of the letter of Title VII, and that the court did not have the power to overturn the language of the Civil Rights Act. Justices Lewis Powell and John Paul Stevens did not participate. Burger wrote the following in the dissent:[4]

| “ | The Court reaches a result I would be inclined to vote for were I a Member of Congress considering a proposed amendment of Title VII. I cannot join the Court's judgment, however, because it is contrary to the explicit language of the statute and arrived at by means wholly incompatible with long-established principles of separation of powers.[5] | ” |

| —Chief Justice Warren Burger | ||

See also

External links

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Justia.com, "Steelworkers v. Weber 443 U.S. 193 (1979)," accessed July 17, 2015

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Oyez.org, "UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA v. WEBER," accessed July 17, 2015

- ↑ PBS, "U.S. Steel Workers of America v. Weber (1979)," accessed July 20, 2015

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 law.cornell.edu, "United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO-CLC v. Weber," accessed July 17, 2015

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.