Daily Brew: September 8, 2025

Welcome to the Monday, Sept. 8, 2025, Brew.

By: Lara Bonatesta

Here’s what’s in store for you as you start your day:

- An early look at the open race for Wisconsin Supreme Court

- This week in 1859, voters in southern California approved a measure to separate from the state and form a new territory. It never happened.

- 23% of August’s elections were uncontested

An early look at the open race for Wisconsin Supreme Court

On Aug. 29, Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Rebecca Bradley announced she would not seek another term in 2026, setting the stage for the third consecutive open race for the court since 2020.

The seat is up for election on April 7, 2026. The primary is scheduled for Feb. 17, 2026. Although the elections are officially nonpartisan, candidates often take stances on specific issues and receive backing from the state's major political parties during their campaigns. For example, Bradley is a member of the court’s three-member conservative block. The court has seven members.

Liberals will have a majority on the court until at least 2028. If a liberal candidate wins in 2026, the liberal majority would increase from 4-3 to 5-2. If a conservative candidate wins, the court would maintain its 4-3 liberal majority.

As of Sept. 4, one candidate, Chris Taylor, has filed to run. Taylor has served as a judge for District IV of the Wisconsin Court of Appeals since she was elected in 2023. Before that, Gov. Tony Evers (D) appointed her as a judge on the Dane County Circuit Court. She was a Democratic member of the Wisconsin state Assembly from 2011 to 2020.

According to the Associated Press' Scott Bauer, "The open race comes as several high-profile issues could make their way to the Wisconsin Supreme Court in the coming months, including abortion, collective bargaining rights, congressional redistricting and election rules."

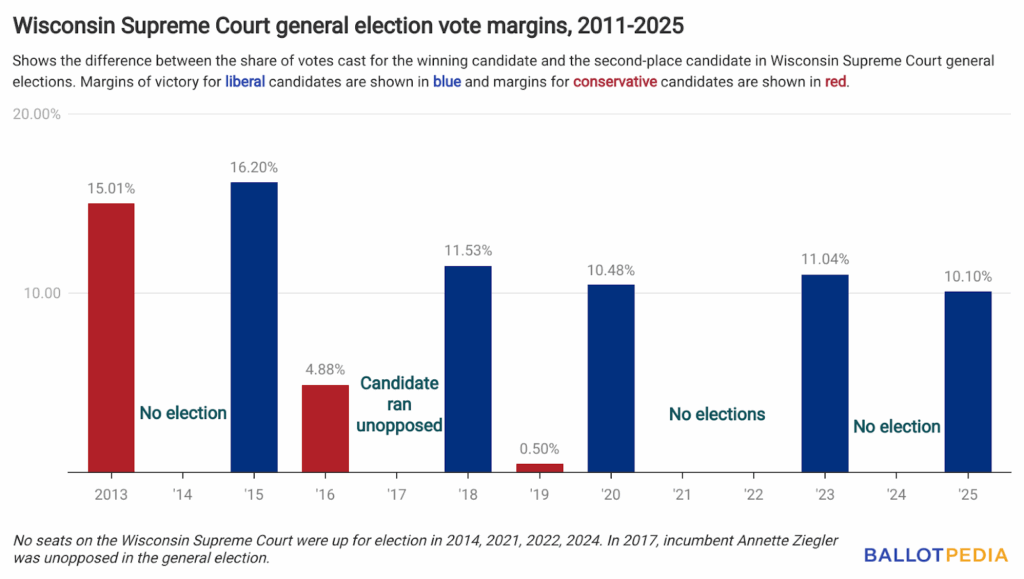

Liberals first won a 4-3 majority in the April 2023 election, when Judge Janet Protasiewicz won an open seat, defeating Daniel Kelly 55.4% to 44.4% and shifting ideological control of the court for the first time in 15 years. In April 2025, liberals retained their 4-3 majority when Susan Crawford defeated Brad Schimel 55.0% to 44.9%.

Both the 2023 and the 2025 races broke records as the most expensive judicial races in U.S. history. According to WisPolitics, the candidates and satellite groups spent more than $100 million in the 2025 election and more than $56 million in the 2023 election.

The last time conservatives won an election for the Wisconsin Supreme Court was in 2019, when Brian Hagedorn defeated Lisa Neubauer 50.2%-49.7%.

The 2025 election also had the record voter turnout for a nonpartisan election at 50%. The previous record was in 2023, when turnout was 39.7%. Turnout in Wisconsin’s November 2024 general election was 73% and turnout in November 2022 was 57.2%.

Wisconsin holds nonpartisan elections for judicial, educational, and municipal offices in its spring general election on the first Tuesday in April. The state holds elections for partisan offices in November.

In addition to the race for state supreme court, Wisconsin is also holding elections for three intermediate appellate court judges in April 2026. In November 2026, the state will hold elections for U.S. House and governor, as well as various other state executive and state legislative offices.

Click here to learn more about the 2026 Wisconsin Supreme Court elections and here to learn more about all of Wisconsin’s 2026 elections.

This week in 1859, voters in southern California approved a measure to separate from the state and form a new territory. It never happened.

On Aug. 26, California Assembly Minority Leader James Gallagher (R-3) introduced Assembly Joint Resolution 23 (AJR 23). The resolution would “express the consent of the Legislature for specified counties to form a new state from within the current boundaries of the State of California, and would urge Congress to accept and embrace that consent.”

Gallagher said the proposal was a response to the Legislature’s approval of Proposition 50 for the Nov. 4, 2025, ballot. Proposition 50 is a constitutional amendment that would allow the state to use a new, legislature-drawn congressional district map for 2026 through 2030. Here’s a brief history of past attempts to divide California into two or more states.

The Pico Act and a history of attempts to divide California

According to the California State Library, at least 220 attempts have been made to divide California since it became a state in 1850. None have been successful.

The Legislature referred one measure to the ballot: the Southern California Creation of Colorado Territory Measure, also known as the Pico Act of 1859. The California Legislature approved Assembly Bill 223 to place the question on the ballot in six counties—Los Angeles, San Bernardino, San Diego, San Luis Obispo, and Tulare. Gov. John B. Weller (D) signed the bill on April 18, 1859, putting the measure on the ballot.

On Sept. 7, 1859, voters approved the Pico Act 74.7%-25.3%. The Pico Act granted consent for the southern counties to establish a separate government with the proposed name Territory of Colorado. The legislation stipulated that a two-thirds vote was needed to approve the measure.

The legislation was named for state Assembly member Andrés Pico (D) of Los Angeles County. According to historian William Henry Ellison, Pico viewed California as "too large and diversified for one state" and that "uniform legislation was unjust and ruinous to the south."

U.S. Sen. Milton Latham (D), writing to Congress on Jan. 12, 1860, said, "They [southern Californians] are an agricultural people, thinly scattered over a large extent of country. They complain that the taxes upon their land and cattle are ruinous—entirely disproportioned to the taxes collected in the mining regions; that the policy of the State, hitherto, having been to exempt mining claims from taxation, and the mining population being migratory in its character, and hence contributing but little to the State revenue in proportion to their population, they are unjustly burdened.”

Creating a new state from an existing state requires more than a bill, resolution, or ballot measure. Article IV, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution requires the state legislature's and Congress's consent. The president must also sign the legislation to create a new state. West Virginia is the most recent state formed from an existing state, separating from Virginia in 1863 during the Civil War.

According to the California State Library, Congress did not take action on the Pico Act due to the Civil War. Patt Morrison, a columnist for the Los Angeles Times, said, "More than a few civic leaders and military men were pro-Dixie, like L.A.'s Civil War-era mayor Damien Marchesseault, who wanted southern California to follow the Confederacy into secession."

Click the following links to learn about more recent ballot measure efforts: State of Jefferson (2016), Six Californias (2016), Cal 3 (2018).

Click here to learn more about the Pico Act and here to learn more about Proposition 50.

23% of August’s elections were uncontested

Ballotpedia will cover more than 32,000 elections this year. Most are for local offices such as city councils, mayors, and school board members – the ones closest to the people. One thing we’ve discovered in our coverage of these races is how many are uncontested, with just one candidate on the ballot (not counting write-in candidates)

Our most recent data from August shows that 23% of the 457 elections we covered in 17 states were uncontested. In July, we covered 31 elections, 29% of which were uncontested.