Daily Brew: September 18, 2025

Welcome to the Thursday, Sept. 18, 2025, Brew.

By: Lara Bonatesta

Here’s what’s in store for you as you start your day:

- Missouri voters to decide on 2026 measure to create a first-of-its-kind citizen initiative supermajority requirement

- Trump Administration uses pocket rescission to withhold funds Congress has appropriated

- This week On The Ballot – Senate changes nomination rules

Missouri voters to decide on 2026 measure to create a first-of-its-kind citizen initiative supermajority requirement

In 2026, Missouri voters will decide on a constitutional amendment that would create a new type of supermajority requirement for citizen-initiated constitutional amendments. The measure, which the state Senate approved on Sept. 12, requires initiated amendments to receive simple majority approval in each congressional district, rather than statewide.

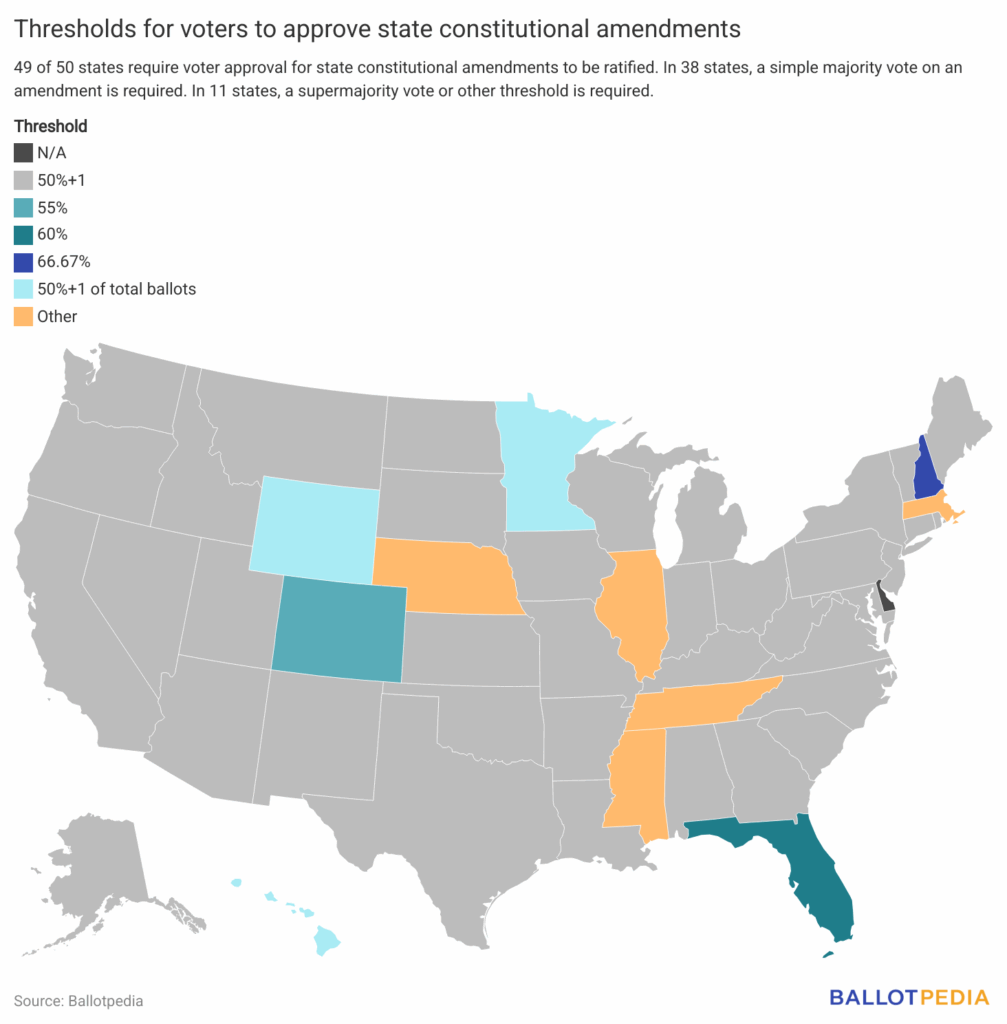

Supermajority requirement ballot measures include those to increase, decrease, or otherwise change the vote threshold to approve certain ballot measure types. Eleven states require supermajority approval for certain ballot measures—for example, a 60% vote to amend the constitution or a higher threshold for tax-related amendments. No state requires voter approval in each congressional district.

Missouri has eight congressional districts. Following the 2024 elections, two districts—District 1 and District 5— have Democratic U.S. representatives, and six districts—Districts 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8—have Republican U.S. representatives. The 2024 winners in all eight districts had double-digit margins of victory. The average margin of victory for Democrats was 40.7 percentage points, and the average margin of victory for Republicans was 37.1 percentage points. Only one representative, Amy Wagner (R), was elected with less than 60% of the vote. Wagner defeated Ray Hartmann (D) 54.5%-42.5% in Missouri’s 2nd Congressional District.

Both chambers of the Missouri General Assembly also voted this month to approve new congressional district boundaries. Click here to learn more about redistricting in Missouri ahead of the 2026 elections.

State Rep. Ed Lewis (R-6) introduced the supermajority amendment as House Joint Resolution 3 (HJR 3) on Sept. 3. On Sept. 9, the House approved HJR 3 98–58. Ninety-eight Republicans voted yes, while 52 Democrats and six Republicans voted no. On Sept. 12, the Senate approved it 21–11. Twenty-one Republicans voted yes, while nine Democrats and two Republicans voted no.

Lewis said, “There are eight congressional districts, and each one of them has exactly the same population. If you can get a majority in each one of those, that is a very broad consensus to just get a majority in each congressional district.”

State Rep. Eric Woods (D), who opposed the amendment said, “We are not applying the same standard here to issues put on the ballot by the legislature is probably the most egregious part of this. You are taking power away from the citizens. You are diluting their votes. It's the same song and dance that we have heard every time, every year that I have been in this chamber.”

The amendment would also prohibit foreign nationals or adversaries of the U.S., as defined in the bill, from contributing to ballot measure campaigns. It would also punish initiative signature fraud as a crime, require public hearings before initiative petitions are placed on the ballot, and make the full text of the initiative available to voters with their ballots. Some of these policies are currently state law, but the proposal would add them to the state constitution with some changes. Nineteen states have laws banning foreign nationals or governments from contributing to ballot measure campaigns, click here to learn more.

Missouri voters will decide on four ballot measures on Nov. 3, 2026. Click here to read more about the supermajority amendment and here to read about what else is on the ballot. Plus, click here to see our comprehensive list of supermajority ballot measures dating back to 1908.

Trump Administration uses pocket rescission to withhold funds Congress has appropriated

A version of this story appeared in the September 2025 edition of Ballotpedia’s Check and Balances newsletter. Click here to sign up.

On Aug. 29, the White House announced that it was canceling $4.9 billion in congressionally appropriated foreign aid through a procedure known as pocket rescission.

Rescission is the process through which the president can request the cancellation of congressionally-appropriated funds. The president can propose rescission of funds in their annual budget request. Additionally, under the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 (ICA), the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) may also send a special message to Congress requesting the rescission of funds.

When Congress receives either type of rescission request, it has 45 days of continuous session to vote to approve, disapprove, or amend the request. Under the ICA, if Congress does not approve the request within 45 days, the OMB must release the funds.

A pocket rescission is when the president requests to rescind unspent funds fewer than 45 days before the funds are scheduled to expire (usually Sept. 30, the end of the federal fiscal year). The OMB may withhold funds proposed for rescission for up to 45 days while Congress considers the request. If Congress does not vote against the rescission before the funds expire, they will lapse unspent, meaning the president effectively cancelled them without needing congressional approval.

No president has used a pocket rescission since the 1970s. In 1975, President Gerald Ford (R) sent a rescission request to Congress for two accounts that were set to expire within the 45-day window. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter (D) submitted rescission requests for two accounts that were set to expire. In both cases, Congress voted on the rescissions after the funds expired, rejecting the 1975 rescissions and approving the 1977 ones. In the 1975 case, Congress also later voted to extend the lapsed appropriations for another fiscal year, overriding a presidential veto.

What are the arguments?

Legislative and executive branch institutions disagree on the legality of pocket rescissions. In 2018, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), a nonpartisan independent agency within the legislative branch, issued an opinion saying that the ICA does not allow pocket rescission. The executive branch Office of Management and Budget disputed this opinion in a 2018 letter to the GAO, saying that pocket rescission is permissible under the ICA and that the GAO had not disputed the validity of pocket rescissions when they were used in the 1970s.

On Aug. 6, the GAO published a blog post saying that pocket rescissions are invalid under the ICA. On Aug. 7, OMB General Council Mark Paoletta responded on X, saying “GAO is wrong on pocket rescissions (the Impoundment Control Act text specifically allows for them).”

The Aug. 29 announcement came after the DC Circuit Court of Appeals lifted an injunction that had blocked the Trump administration from freezing foreign aid funds, including the $4.9 billion. On Sept. 3, a U.S. federal district court judge issued an injunction requiring the Trump administration to spend $11.5 billion in appropriated foreign aid, including the $4.9 billion, before the end of the fiscal year. The U.S. Supreme Court temporarily lifted this injunction on Sept. 9.

Background

Before Congress passed the ICA in 1974, presidents commonly practiced impoundment and refrained from spending appropriated funds. The ICA effectively banned impoundment, requiring the OMB to release funds at the end of the 45-day congressional review window if Congress does not approve a rescission request.

Earlier this year, Trump submitted a package of rescission requests to Congress. The House of Representatives approved it 216-213, and the Senate approved it 51-48. Trump signed the package into law on July 24. The package rescinded approximately $8 billion in appropriated foreign aid funding and $1 billion appropriated for public broadcasting.

Click here to learn more about the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974.

This week On The Ballot – Senate changes nomination rules

In this week's new episode of On the Ballot, host Norm Leahy and Roll Call’s Ryan Tarinelli discuss the U.S. Senate’s Sept. 11 vote to change the chamber’s rules on the confirmation process for certain presidential nominees.

ICYMI, the change allows Senators to confirm multiple nominees at once with a simple majority vote, instead of voting on each one separately. This applies to ambassador and executive agency nominees. Cabinet-level and judicial nominees still require individual votes. The vote was 53-45, along party lines.

Tarinelli breaks down the change, why it happened, and what it might mean for the nomination process, congressional oversight, and Senate comity in the future.

As we mentioned in our Sept. 15 edition of the Daily Brew, when a majority party changes a Senate rule or precedent with a simple majority vote, it’s often called the “nuclear option” or “constitutional option.” To learn more about previous uses of the nuclear option, click here.

Subscribe to On The Ballot on YouTube or your preferred podcast app, or click here to listen.