Federal environmental regulation in New Mexico

![]() This article does not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

This article does not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

![]() This article does not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

This article does not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

| Public Policy |

|---|

|

Federal environmental regulation involves the implementation of federal environmental laws, such as the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is primarily responsible for enforcing federal air and water quality standards; the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is primarily responsible for managing endangered species. State government agencies will often share enforcement responsibilities with the EPA on issues such as air pollution, water pollution, hazardous waste, and other environmental issues.[1]

Legislation and regulation

Federal laws

Clean Air Act

The federal Clean Air Act requires each state to meet federal standards for air pollution. Under the act, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency oversees national air quality standards aimed at limiting pollutants from chemical plants, steel mills, utilities, and industrial factories. Individual states can enact stricter air standards if they choose, though each state must adhere to the EPA's minimum pollution standards. States implement federal air standards through a state implementation plan (SIP), which must be approved by the EPA.[2]

Clean Water Act

The federal Clean Water Act is meant to address and maintain the physical, chemical, and biological status of the waters of the United States. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates water pollution sources and provides financial assistance to states and municipalities for water quality programs.[3]

According to research done by The New York Times using annual averages from 2004 to 2007, New Mexico had 126 facilities that were regulated annually by the Clean Water Act. An average of 72.2 facilities violated the act annually from 2004 to 2007 in New Mexico, and the EPA enforced the act an average of 9.8 times a year in the state. This information, published by the Times in 2009, was the most recent information on the subject as of October 2014.[4]

The table below shows how New Mexico compared to neighboring states in The New York Times study, including the number of regulated facilities, facility violations, and the annual average of enforcement actions against regulated facilities between 2004 and 2007.

| The New York Times Clean Water Act study (2004-2007) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Number of facilities regulated | Facility violations | Annual average enforcement actions | |

| New Mexico | 126 | 72.2 | 9.8 | |

| Arizona | 158 | 61.1 | 1.2 | |

| Colorado | 351.8 | 232.7 | 6.5 | |

| Utah | 119.80 | 53.50 | 3.30 | |

| Source: The New York Times, "Clean Water Act Violations: The Enforcement Record" | ||||

Endangered Species Act

The federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973 provides for the identification, listing, and protection of both threatened and endangered species and their habitats. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the law was designed to prevent the extinction of vulnerable plant and animal species through the development of recovery plans and the protection of critical habitats. ESA administration and enforcement are the responsibility of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service.[5][6]

Federally listed species in New Mexico

There were 55 endangered and threatened animal and plant species believed to or known to occur in New Mexico as of July 2015.

The table below lists the 42 endangered and threatened animal species believed to or known to occur in the state. When an animal species has the word "Entire" after its name, that species will be found all throughout the state.[7]

| Endangered animal species in New Mexico | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status | Species | ||||||

| Endangered | Amphipod, Noel's (Gammarus desperatus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Bat, lesser long-nosed Entire (Leptonycteris curasoae yerbabuenae) | ||||||

| Endangered | Bat, Mexican long-nosed Entire (Leptonycteris nivalis) | ||||||

| Threatened | Chub, Chihuahua Entire (Gila nigrescens) | ||||||

| Endangered | Chub, Gila Entire (Gila intermedia) | ||||||

| Threatened | Cuckoo, yellow-billed Western U.S. DPS (Coccyzus americanus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Ferret, black-footed entire population, except where EXPN (Mustela nigripes) | ||||||

| Endangered | Flycatcher, southwestern willow Entire (Empidonax traillii extimus) | ||||||

| Threatened | Frog, Chiricahua leopard Entire (Rana chiricahuensis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Gambusia, Pecos Entire (Gambusia nobilis) | ||||||

| Threatened | gartersnake, northern Mexican (Thamnophis eques megalops) | ||||||

| Endangered | Isopod, Socorro Entire (Thermosphaeroma thermophilus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Jaguar U.S.A(AZ,CA,LA,NM,TX),Mexico,Central and South America (Panthera onca) | ||||||

| Threatened | Lynx, Canada (Contiguous U.S. DPS) (Lynx canadensis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Minnow, loach Entire (Tiaroga cobitis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Minnow, Rio Grande Silvery Entire, except where listed as an experimental population (Hybognathus amarus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Mouse, New Mexico meadow jumping (Zapus hudsonius luteus) | ||||||

| Threatened | Owl, Mexican spotted Entire (Strix occidentalis lucida) | ||||||

| Endangered | Pikeminnow (=squawfish), Colorado Entire, except EXPN (Ptychocheilus lucius) | ||||||

| Threatened | Plover, piping except Great Lakes watershed (Charadrius melodus) | ||||||

| Threatened | Prairie-chicken, lesser (Tympanuchus pallidicinctus) | ||||||

| Threatened | Rattlesnake, New Mexican ridge-nosed Entire (Crotalus willardi obscurus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Salamander, Jemez Mountains (Plethodon neomexicanus) | ||||||

| Threatened | Shiner, Arkansas River Arkansas R. Basin (Notropis girardi) | ||||||

| Threatened | Shiner, beautiful Entire (Cyprinella formosa) | ||||||

| Threatened | Shiner, Pecos bluntnose Entire (Notropis simus pecosensis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Snail, Pecos assiminea (Assiminea pecos) | ||||||

| Threatened | Snake, narrow-headed garter (Thamnophis rufipunctatus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Spikedace Entire (Meda fulgida) | ||||||

| Endangered | Springsnail, Alamosa Entire (Tryonia alamosae) | ||||||

| Endangered | Springsnail, Chupadera (Pyrgulopsis chupaderae) | ||||||

| Endangered | Springsnail, Koster's (Juturnia kosteri) | ||||||

| Endangered | Springsnail, Roswell (Pyrgulopsis roswellensis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Springsnail, Socorro Entire (Pyrgulopsis neomexicana) | ||||||

| Endangered | Sucker, razorback Entire (Xyrauchen texanus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Sucker, Zuni bluehead (Catostomus discobolus yarrowi) | ||||||

| Endangered | Tern, least interior pop. (Sterna antillarum) | ||||||

| Endangered | Topminnow, Gila (incl. Yaqui) U.S.A. only (Poeciliopsis occidentalis) | ||||||

| Threatened | Trout, Gila Entire (Oncorhynchus gilae) | ||||||

| Endangered | Wolf, gray | ||||||

| Endangered | Wolf, Mexican gray Entire, except where an experimental population (Canis lupus baileyi) | ||||||

| Endangered | Woundfin Entire, except EXPN (Plagopterus argentissimus) | ||||||

| Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Endangered and threatened species in New Mexico" | |||||||

The table below lists the 13 endangered and threatened plant species believed to or known to occur in the state.[7]

| Endangered plant species in New Mexico | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status | Species | ||||||

| Endangered | Cactus, Knowlton's (Pediocactus knowltonii) | ||||||

| Endangered | Cactus, Kuenzler hedgehog (Echinocereus fendleri var. kuenzleri) | ||||||

| Threatened | Cactus, Lee pincushion (Coryphantha sneedii var. leei) | ||||||

| Threatened | Cactus, Mesa Verde (Sclerocactus mesae-verdae) | ||||||

| Endangered | Cactus, Sneed pincushion (Coryphantha sneedii var. sneedii) | ||||||

| Threatened | Fleabane, Zuni (Erigeron rhizomatus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Ipomopsis, Holy Ghost (Ipomopsis sancti-spiritus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Milk-vetch, Mancos (Astragalus humillimus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Pennyroyal, Todsen's (Hedeoma todsenii) | ||||||

| Endangered | Poppy, Sacramento prickly (Argemone pleiacantha ssp. pinnatisecta) | ||||||

| Threatened | Sunflower, Pecos (=puzzle, =paradox) (Helianthus paradoxus) | ||||||

| Threatened | Thistle, Sacramento Mountains (Cirsium vinaceum) | ||||||

| Threatened | Wild-buckwheat, gypsum (Eriogonum gypsophilum) | ||||||

| Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Endangered and threatened species in New Mexico" | |||||||

State-listed species in New Mexico

Under the New Mexico Wildlife Conservation Act, the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish manages the state's list of endangered and threatened species and manages recovery and conservation efforts for these species. The complete list of endangered and threatened species as of July 2015 can be found here.

Enforcement

- See also: Enforcement at the EPA

New Mexico is part of the EPA's Region 6, which includes Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Arkansas.[8]

The EPA enforces federal standards on air, water and hazardous chemicals. The EPA can engage in its own administrative action against private industries, or it can bring civil and/or criminal lawsuits against them. The goal of environmental law enforcement is usually the collection of penalties and fines for violations of laws like the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act. In 2013, the EPA estimated that 117.1 million pounds of pollution, which includes air pollution, water contaminants, and hazardous chemicals, were "reduced, treated or eliminated" and 61,289 cubic yards of soil and water were cleaned in Region 6. Additionally, 439 enforcement cases were initiated, and 443 enforcement cases were concluded in fiscal year 2013. In fiscal year 2012, the EPA collected $252 million in criminal fines and civil penalties from the private sector nationwide. In fiscal year 2013, the EPA collected $1.1 billion in criminal fines and civil penalties from the private sector nationwide, primarily due to the $1 billion settlement from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill along the Gulf Coast in 2010.[9][10][11][12]

Mercury and air toxics standards

- See also: Mercury and air toxics standards

The EPA enforces mercury and air toxics standards (MATS), which are national limits on mercury, chromium, nickel, arsenic and acidic gases from coal- and oil-fired power plants. Power plants are required to have certain technologies to limit these pollutants. In December 2011, the EPA issued greater restrictions on the amount of mercury and other toxic pollutants produced by power plants. As of 2014, approximately 580 power plants, including 1,400 oil- and coal-fired electric-generating units, fell under the federal rule. The EPA has claimed that power plants account for 50 percent of mercury emissions, 75 percent of acidic gases and around 20 to 60 percent of toxic metal emissions in the United States. All coal- and oil-fired power plants with a capacity of 25 megawatts or greater are subject to the standards. The EPA has claimed that the standards will "prevent up to 24 premature deaths in New Mexico while creating up to $200 million in health benefits in 2016."[13][14][15][13][16]

In 2014, the EPA released a study examining the economic, environmental, and health impacts of the MATS standards nationwide. Other organizations have released their own analyses about the effects of the MATS standards. Below is a summary of the studies on MATS and their effects as of November 2014.

EPA study

In 2014, the EPA argued that its MATS rule would prevent roughly 11,000 premature deaths and 130,000 asthma attacks nationwide. The agency also anticipated between $37 billion and $90 billion in "improved air quality benefits" annually. For the rule's cost, the EPA estimated that annual compliance fees for coal- and oil-fired power plants would reach $9.6 billion.[17]

NERA study

A 2012 study published by NERA Economic Consulting, a global consultancy group, reported that annual compliance costs in the electricity sector would total $10 billion in 2015 and nearly $100 billion cumulatively up through 2034. The same study found that the net impact of the MATS rule in 2015 would be the income equivalent of 180,000 fewer jobs. This net impact took into account the job gains associated with the building and refitting of power plants with new technology.[18]

Superfund sites

The EPA established the Superfund program as part of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act of 1980.The Superfund program focuses on uncontrolled or abandoned hazardous waste sites nationwide. The EPA inspects waste sites and establishes cleanup plans for them. The federal government can compel the private entities responsible for a waste site to clean the site or face penalties. If the federal government cleans a waste site, it can force the responsible party to reimburse the EPA or other federal agencies for the cleanup's cost. Superfund sites include oil refineries, smelting facilities, mines and other industrial areas. As of October 2014, there were 1,322 Superfund sites nationwide. A total of 91 Superfund sites reside in Region 6, with an average of 18.2 sites per state. There were 15 Superfund sites in New Mexico as of October 2014.[19][20]

Economic impact

| EPA studies |

|---|

| The Environmental Protection Agency publishes studies to evaluate the impact and benefits of its policies. Other studies may dispute the agency's findings or state the costs of its policies. |

According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), an independent federal agency, the Superfund program received an average of almost $1.2 billion annually in appropriated funds between the years 1981 and 2009, adjusted for inflation. The GAO estimated that the trust fund of the Superfund program decreased from $5 billion in 1997 to $137 million in 2009. The Superfund program received an additional $600 million in federal funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, also known as the stimulus bill.[21]

In March 2011, the EPA claimed that the agency's Superfund program produced economic benefits nationwide. Because Superfund sites are added and removed from a prioritized list on a regular basis, the total number of Superfund sites since the program's inception in 1980 is unknown. Based on a selective study of 373 Superfund sites cleaned up since the program's inception, the EPA estimated these economic benefits include the creation of 2,240 private businesses, $32.6 billion in annual sales from new businesses, 70,144 jobs and $4.9 billion in annual employment income.[22]

Other studies were published detailing the costs associated with the Superfund program. According to the Property and Environment Research Center, a free market-oriented policy group based in Montana, the EPA spent over $35 billion on the Superfund program between 1980 and 2005.[23][24]

Environmental impact

In March 2011, the EPA claimed that the Superfund program resulted in healthier environments surrounding former waste sites. An agency study analyzed the program's health and ecological benefits and focused on former landfills, mining areas, and abandoned dumps that were cleaned up and renovated. As of January 2009, out of the approximately 500 former Superfund sites used for the study, roughly 10 percent became recreational or commercial sites. Other former Superfund sites in the study are now used as wetlands, meadows, streams, scenic trails, parks, and habitats for plants and animals.[25]

Carbon emissions

- See also: Climate change, Greenhouse gas and Greenhouse gas emissions by state

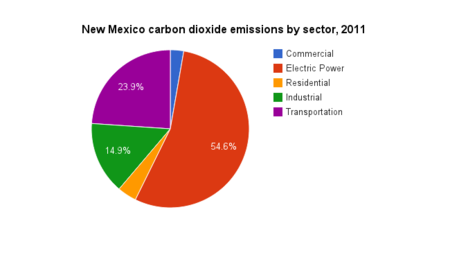

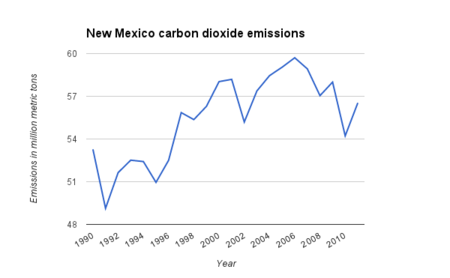

In 2011, New Mexico ranked 35th nationwide in CO2 emissions, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. New Mexico's emissions have fluctuated between 1990 and 2011. Emissions peaked in 2006 at 60 million metric tons of CO2. In 2011, most of the state's emissions came from the electric power sector (54.6 percent) and nearly one-quarter came from the transportation sector. The commercial, residential and industrial sectors accounted for the remainder.[26]

Carbon dioxide emissions in New Mexico (in million metric tons). Data was compiled by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. |

Pollution from energy use

Pollution from energy use includes three common air pollutants: carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and ozone. These and other pollutants are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) through the National Ambient Air Quality Standards, which are federal standards limiting pollutants that can harm human health in significant concentrations. Carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, is also regulated by the EPA, but it is excluded here since it is not one of the pollutants originally regulated under the Clean Air Act for its harm to human health.

Industries and motor vehicles emit carbon monoxide directly when they use energy. Nitrogen dioxide forms from the emissions of automobiles, power plants and other sources. Ground level ozone (also known as tropospheric ozone) is not emitted but is the product of chemical reactions between nitrogen dioxide and volatile organic chemicals. The EPA tracks these and other pollutants from monitoring sites across the United States. The data below shows nationwide and regional trends for carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and ozone between 2000 and 2014. States with consistent climates and weather patterns were grouped together by the EPA to make up each region.[27][28]

Carbon monoxide (CO)

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colorless, odorless gas produced from combustion processes, e.g., when gasoline reacts rapidly with oxygen and releases exhaust; the majority of national CO emissions come from mobile sources like automobiles. CO can reduce the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and at very high levels can cause death. CO concentrations are measured in parts per million (ppm). Since 1994, federal law prohibits CO concentrations from exceeding 9 ppm during an eight-hour period more than once per year.[29][30]

The chart below compares the annual average concentration of carbon monoxide (CO) in the Southern and Southwestern regions of the United States between 2000 and 2014. Carbon monoxide concentrations are measured in parts per million (ppm). States with consistent climates and weather patterns were grouped together by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which collects these data, to make up each region. Each line represents the annual average of all the data collected from pollution monitoring sites in each region. In the South, there were 18 monitoring sites throughout six states. In the Southwest, there were 24 monitoring sites throughout four states. In 2000, the average concentration of carbon monoxide was 3.84 ppm in the South, compared to 4.05 ppm in the Southwest. In 2014, the average concentration of carbon monoxide was 1.28 ppm in the South, a decrease of 66.6 percent from 2000, compared to 1.63 ppm in the Southwest, a decrease of 59.9 percent from 2000.[31]

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2)

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is one of a group of gasses known as nitrogen oxides (NOx). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) measures NO2 as a representative for the larger group of nitrogen oxides. NO2 forms from the emissions of cars, buses, trucks, power plants, and off-road equipment. It helps form ground-level ozone and fine particle pollution, and has been linked to respiratory problems. Since 1971, federal law prohibits NO2 concentrations from exceeding a daily one-hour average of 100 parts per billion (ppb) and an annual average of 53 parts per billion (ppb).[30][32][30]

The chart below compares the annual one-hour average concentration of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) in the Southern and Southwestern regions of the United States between 2000 and 2014. In the South, there were 34 monitoring sites throughout six states, compared to 10 monitoring sites throughout four states in the Southwest. In 2000, the one-hour daily average concentration of NO2 was 50.24 ppb in the South, compared to 71.5 ppb in the Southwest. In 2014, the one-hour daily average concentration of NO2 was 36.77 ppb in the South, a decrease of 26.8 percent since 2000, compared to 49.35 ppb in the Southwest, a decrease of 30.9 percent since 2000.[33]

Ground-level ozone

Ground-level ozone is created by chemical reactions between nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in sunlight. Major sources of NOx and VOCs include industrial facilities, electric utilities, automobiles, gasoline vapors, and chemical solvents. Ground-level ozone can produce health problems for children, the elderly, and asthmatics. Since 2008, federal law has prohibited ozone concentrations from exceeding a daily eight-hour average of 75 parts per billion (ppb). Beginning in 2025, federal law will prohibit ground-level ozone concentrations from exceeding a daily eight-hour average of 70 ppb.[30][34]

The chart below compares the daily eight-hour average concentration of ground-level ozone in the Southern and Southwestern regions of the United States between 2000 and 2014. In the chart below, ozone concentrations are measured in parts per million (ppm), which can be converted to parts per billion (ppb). In the South, there were 110 monitoring sites throughout six states, compared to 63 monitoring sites throughout four states in the Southeast. In 2000, the daily eight-hour average concentration of ozone was 0.0873 ppm, or 87.3 ppb in the South, compared to 0.0773 ppm, or 77.3 ppb in the Southwest. In 2014, the daily eight-hour average concentration of ozone was 0.0661 ppm, or 66.1 ppb in the South, a decrease of 24.2 percent since 2000, compared to 0.0692 ppm, or 69.2 ppb in the Southwest, a decrease of 10.5 percent since 2000.[35]

Environmental policy in the 50 states

Click on a state below to read more about that state's energy policy.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Laws & Regulations," accessed November 25, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Understanding the Clean Air Act," accessed September 12, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Clean Water Act (CWA) Overview," accessed September 19, 2014

- ↑ The New York Times, "Clean Water Act Violations: The Enforcement Record," September 13, 2009

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Improving ESA Implementation," accessed May 15, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "ESA Overview," accessed October 1, 2014

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Endangered and threatened species in STATE," accessed July 6, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "EPA Region 6 (South Central)," accessed November 13, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Annual EPA Enforcement Results Highlight Focus on Major Environmental Violations," February 7, 2014

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency, "Accomplishments by EPA Region (2013)," May 12, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Enforcement Annual Results for Fiscal Year 2012," accessed October 1, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "EPA Enforcement in 2012 Protects Communities From Harmful Pollution," December 17, 2012

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Cleaner Power Plants," accessed January 5, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Basic Information on Mercury and Air Toxics Standards," accessed January 5, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Basic Information on Mercury and Air Toxics Standards," accessed January 5, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Mercury and Air Toxics Standards in New Mexico," accessed September 9, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Benefits and Costs of Cleaning Up Toxic Air Pollution from Power Plants," accessed October 9, 2014

- ↑ NERA Economic Consulting, "An Economic Impact Analysis of EPA's Mercury and Air Toxics Standards Rule," March 1, 2012

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "What is Superfund?" accessed September 9, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "National Priorities List (NPL) of Superfund Sites," accessed October 7, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Government Accountability Office, "EPA's Estimated Costs to Remediate Existing Sites Exceed Current Funding Levels, and More Sites Are Expected to Be Added to the National Priorities List," accessed October 7, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Estimate of National Economic Impacts of Superfund Sites," accessed September 12, 2014

- ↑ Property and Environment Research Center, "Superfund Follies, Part II," accessed October 7, 2014

- ↑ Property and Environment Research Center, "Superfund: The Shortcut That Failed (1996)," accessed October 7, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Beneficial Effects of the Superfund Program," accessed September 12, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Energy Information Administration, "State Profiles and Energy Estimates," accessed October 13, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Air Trends," accessed October 30, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Basic Information - Ozone," accessed January 1, 2016

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Carbon Monoxide," accessed October 26, 2015

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS)," accessed October 26, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Regional Trends in CO Levels," accessed October 23, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Nitrogen dioxide," accessed October 26, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Regional Trends in Nitrogen Dioxide Levels," accessed October 23, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Ground Level Ozone," accessed October 26, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Regional Trends in Ozone Levels ," accessed October 26, 2015