Injection well

This article does not receive scheduled updates. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia. Contact our team to suggest an update.

| Energy in the 50 states |

|---|

Injection wells are shafts in the ground that are used to store fluid or other substances such as carbon dioxide (CO2). There are a variety of injection wells, some of which are shallow and used to store water and non-hazardous liquids. Other wells are deep underground and used to store wastewater, salt water (brine), or a mixture of water and chemicals (this page focuses on these deeper wells). Injection wells have been used since at least 300 A.D. by the Chinese for the extraction of salt under the earth's surface. The widespread use of injection wells to dispose of waste from the extraction of oil and natural gas began in the 1930s in Texas.[1][2][3]

In 1974 Congress passed the Safe Drinking Water Act, which gave the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) the authority to regulate underground injection wells. The EPA classified injection wells into six different types (Class I through Class VI). A table explaining the types of wells is available below. This page focuses on Class II wells, which are part of the oil and natural gas extraction process.[1][2][3]

The EPA defines an injection well as

| “ | a device that places fluid deep underground into porous rock formations, such as sandstone or limestone, or into or below the shallow soil layer. These fluids may be water, wastewater, brine (salt water), or water mixed with chemicals.[4] | ” |

| —U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Basic Information about Injection Wells" | ||

| Types of injection wells | ||

|---|---|---|

| Well class | Type | Number of wells (2012) |

| Class I | "hazardous wastes, industrial non-hazardous liquids, or municipal wastewater" | 650 wells |

| Class II | "brines and other fluids associated with oil and gas production, and hydrocarbons" | 172,068 wells |

| Class III | remaining mining solutions | 22,131 wells |

| Class IV | "hazardous or radioactive wastes ... These wells are banned unless authorized under a federal or state ground water remediation project." | 33 sites |

| Class V | "non-hazardous fluids" | 400,000 wells to 650,000 wells |

| Class VI | carbon dioxide (CO2) | 6 wells to 10 wells expected by 2016 |

| Source:U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Classes of Wells" | ||

Implementation

How an injection well is constructed depends on the well class, the type of liquid that will be injected and the depth to which the well will extend. Injection wells that store only drinking water and other non-hazardous fluids are usually very shallow. Injection wells that house hazardous liquids and carbon dioxide are located deep underground, and are encased in cement and steel casing. The type of cement, type of casing and other factors are regulated by the EPA.

Regulation

- See also: The Safe Drinking Water Act and fracking

Injection wells are regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), which was passed in 1974. The SDWA required the EPA to assess waste disposal practices, develop requirements for these wells and prevent underground sources of drinking water from becoming contaminated. Underground sources of drinking water are aquifers that currently or one day could supply drinking water. These regulations are enforced by the EPA's regional office, state environmental protection agencies or tribal authorities. The "EPA has delegated primacy for all well classes to 33 states and 3 territories; it shares responsibility in 7 states, and implements a program for all well classes in 10 states, 2 territories, the District of Columbia, and most Tribes."[1][2][3] Read more about the EPA's regulations here.

Injection wells and fracking

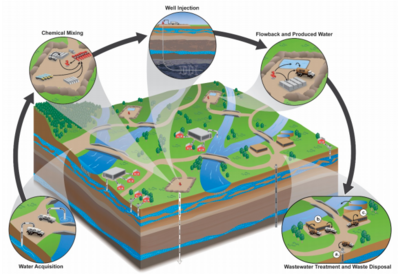

Injection wells have received increased attention for the role they play in hydraulic fracturing—fracking—process. Fracking is a process to stimulate oil production from wells in oil reservoirs. Fluid is injected into the ground at a high pressure in order to fracture shale rocks for hydrocarbons, including natural gas, inside. Fracking can also release trapped oil and water, known as produced water. More than 90 percent of new oil and gas wells utilize fracking.[5][6]

The wastewater produced after fracking a well is often stored in a deep injections wells. Injection wells are generally considered the safest and most cost-effective place for wastewater to be stored. According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), "of more than 150,000 Class II injection wells in the United States, roughly 40,000 are waste fluid disposal wells for oil and gas operations. Only a small fraction of these disposal wells have induced earthquakes that are large enough to be of concern to the public."[7][8][9][10]

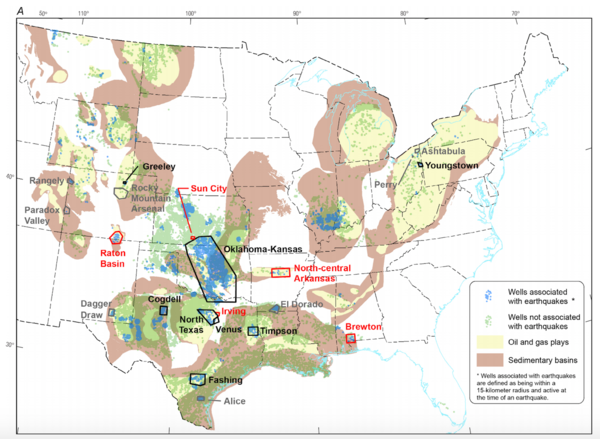

There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that this growth in the number of earthquakes has been caused by the increased use of injection wells to dispose of fracking wastewater. While fracking has been rarely known to cause earthquakes, there is an established scientific link between earthquakes and the disposal of fluids in deep, underground injection wells. The map below shows earthquakes that have occurred in the last 50 years that the USGS believes were caused by "induced seismology," or man-made earthquakes, due to the disposal of fracking wastewater or oil and natural gas extraction.[10]

Concerns

Even though scientists at the USGS have been able to cause earthquakes intentionally by carefully injecting liquid into the earth, the link between injection wells and earthquakes is not fully understood. One of the largest concerns for scientists and regulators is that they do not have the tools to predict whether wastewater will cause seismic activity. These concerns are compounded by the lack of knowledge about where faults are located across the central and eastern United States. The USGS is beginning to map these areas in more detail in order to understand the seismic risks. As of June 2014, these earthquakes had typically been small, two or three in magnitude on the Richter scale, but at least one scientist has raised concerns that earthquakes could grow in intensity if old injection wells continue to be used for wastewater storage.[8][11]

Energy in the 50 states

Click on a state below to read more about that state's energy policy.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "History of the UIC Program - Injection Well Time Line," May , 2012

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Basic Information about Injection Wells," May 4, 2012

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Classes of Wells," August 2, 2012

- ↑ Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ Frack Wire, “What is Fracking,” accessed January 28, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Congressional Research Service, "Hydraulic Fracturing and Safe Drinking Water Act Regulatory Issues," January 10, 2013

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey, "USGS FAQs," March 18, 2015

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 U.S. Geological Survey, "Man-Made Earthquakes Update," January 17, 2014, accessed March 10, 2014

- ↑ National Public Radio, "How Oil and Gas Disposal Wells Can Cause Earthquakes," accessed June 2, 2014

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 United States Geological Survey, "Incorporating Induced Seismicity in the 2014 United States National Seismic Hazard Model—Results of 2014 Workshop and Sensitivity Studies," 2015

- ↑ National Geographic, "Scientists Warn of Quake Risk From Fracking Operations," May 2, 2014