Historical Texas environmental information, 1913-2016

![]() This article does not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

This article does not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

The historical environmental information below applies to prior years. For more current information regarding environmental policy in Texas, see this article.

Land ownership

- See also: Federal land policy and Federal land ownership by state

The federal government owned between 635 million and 640 million acres of land in 2012 (about 28 percent) of the 2.27 billion acres of land in the United States. Around 52 percent of federally owned acres were in 12 Western states—including Alaska, 61 percent of which was federally owned. In contrast, the federal government owned 4 percent of land in the other 38 states. Federal land policy is designed to manage minerals, oil and gas resources, timber, wildlife and fish, and other natural resources found on federal land. Land management policies are highly debated for their economic, environmental and social impacts. Additionally, the size of the federal estate and the acquisition of more federal land are major issues.[1][2]

According to the Congressional Research Service, Texas spans 168.2 million acres. Of that total, 1.7 percent, or 2.97 million acres, belonged to the federal government as of 2012. More than 167 million acres in Texas are not owned by the federal government, or 6.34 non-federal acres per capita. From 1990 to 2010, the federal government's land ownership in Texas increased by 326,275 acres.[1]

The table below shows federal land ownership in Texas compared to two neighboring states, New Mexico and Oklahoma. Texas had less federal land than New Mexico but more Oklahoma. More than 40 percent of federal land in Texas was owned by the U.S. Forest Service compared to 1.4 percent in New Mexico and 1.42 percent in Oklahoma. The U.S. National Park Service owned more than 1.2 million acres in Texas compared to 376,849 acres in New Mexico and 10,008 acres in Oklahoma.

| Federal land owned in Texas and neighboring states by federal agency | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | |||||||||||

| Agency | Texas | New Mexico | Oklahoma | ||||||||

| Acres owned | Percentage owned | Acres owned | Percentage owned | Acres owned | Percentage owned | ||||||

| U.S. Forest Service | 755,365 | 25.37% | 9,417,975 | 34.88% | 400,928 | 57.00% | |||||

| U.S. National Park Service | 1,201,670 | 40.35% | 376,849 | 1.40% | 10,008 | 1.42% | |||||

| U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service | 527,418 | 17.71% | 327,264 | 1.21% | 106,594 | 15.16% | |||||

| U.S. Bureau of Land Management | 11,833 | 0.40% | 13,484,405 | 49.94% | 1,975 | 0.28% | |||||

| U.S. Department of Defense | 481,664 | 16.17% | 3,395,090 | 12.57% | 183,831 | 26.14% | |||||

| Total federal land | 2,977,950 | 100% | 27,001,583 | 100% | 703,336 | 100% | |||||

| Source: Congressional Research Service, "Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data" | |||||||||||

Land usage

Recreation

National parks in Texas

Texas has 13 National Park Service units, one national monument, three national forests, six wilderness areas, two national recreation areas, one national historic site, and one national historic trail. A study by the U.S. National Park Service found that 3.4 million peopled visited Texas's national parks and monuments and generated $173.4 million in visitor spending in 2013.[3]

State recreation lands

There are 103 state parks in Texas, which are listed in the table below.[4]

| State parks in Texas | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State park name | ||||||

| Abilene State Park | ||||||

| Atlanta State Park | ||||||

| Balmorhea State Park | ||||||

| Barton Warnock Visitor Center | ||||||

| Bastrop State Park | ||||||

| Battleship Texas State Historic Site | ||||||

| Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park | ||||||

| Big Bend Ranch State Park | ||||||

| Big Spring State Park | ||||||

| Blanco State Park | ||||||

| Bonham State Park | ||||||

| Brazos Bend State Park | ||||||

| Buescher State Park | ||||||

| Caddo Lake State Park | ||||||

| Caprock Canyons State Park | ||||||

| Caprock Canyons Trailway | ||||||

| Cedar Hill State Park | ||||||

| Choke Canyon State Park - Calliham Unit | ||||||

| Choke Canyon State Park - South Shore Unit | ||||||

| Cleburne State Park | ||||||

| Colorado Bend State Park | ||||||

| Cooper Lake State Park - Doctors Creek Unit | ||||||

| Cooper Lake State Park - South Sulphur Unit | ||||||

| Copper Breaks State Park | ||||||

| Daingerfield State Park | ||||||

| Davis Mountains State Park | ||||||

| Devil`s Sinkhole State Natural Area | ||||||

| Devils River State Natural Area | ||||||

| Dinosaur Valley State Park | ||||||

| Eisenhower State Park | ||||||

| Enchanted Rock State Natural Area | ||||||

| Estero Llano Grande State Park | ||||||

| Fairfield Lake State Park | ||||||

| Falcon State Park | ||||||

| Fanthorp Inn State Historic Site | ||||||

| Fort Boggy State Park | ||||||

| Fort Leaton State Historic Site | ||||||

| Fort Parker State Park | ||||||

| Fort Richardson State Park & Historic Site / Lost Creek Reservoir State Trailway | ||||||

| Franklin Mountains State Park | ||||||

| Galveston Island State Park | ||||||

| Garner State Park | ||||||

| Goliad State Park & Historic Site | ||||||

| Goose Island State Park | ||||||

| Government Canyon State Natural Area | ||||||

| Guadalupe River State Park | ||||||

| Hill Country State Natural Area | ||||||

| Honey Creek State Natural Area | ||||||

| Hueco Tanks State Park & Historic Site | ||||||

| Huntsville State Park | ||||||

| Indian Lodge | ||||||

| Inks Lake State Park | ||||||

| Kickapoo Cavern State Park | ||||||

| Lake Arrowhead State Park | ||||||

| Lake Bob Sandlin State Park | ||||||

| Lake Brownwood State Park | ||||||

| Lake Casa Blanca International State Park | ||||||

| Lake Colorado City State Park | ||||||

| Lake Corpus Christi State Park | ||||||

| Lake Livingston State Park | ||||||

| Lake Mineral Wells State Park | ||||||

| Lake Mineral Wells Trailway | ||||||

| Lake Somerville State Park - Birch Creek Unit | ||||||

| Lake Somerville State Park - Nails Creek Unit | ||||||

| Lake Tawakoni State Park | ||||||

| Lake Whitney State Park | ||||||

| Lipantitlan State Historic Site | ||||||

| Lockhart State Park | ||||||

| Longhorn Cavern State Park | ||||||

| Lost Maples State Natural Area | ||||||

| Lyndon B. Johnson State Park & Historic Site | ||||||

| Martin Creek Lake State Park | ||||||

| Martin Dies, Jr. State Park | ||||||

| Mckinney Falls State Park | ||||||

| Meridian State Park | ||||||

| Mission Rosario State Historic Site | ||||||

| Mission Tejas State Park | ||||||

| Monahans Sandhills State Park | ||||||

| Monument Hill & Kreische Brewery State Historic Site | ||||||

| Mother Neff State Park | ||||||

| Mustang Island State Park | ||||||

| Old Tunnel State Park | ||||||

| Palmetto State Park | ||||||

| Palo Duro Canyon State Park | ||||||

| Pedernales Falls State Park | ||||||

| Port Isabel Lighthouse State Historic Site | ||||||

| Possum Kingdom State Park | ||||||

| Purtis Creek State Park | ||||||

| Ray Roberts Lake State Park - Isle du Bois Unit | ||||||

| Ray Roberts Lake State Park - Johnson Branch Unit | ||||||

| Resaca de la Palma State Park | ||||||

| San Angelo State Park | ||||||

| San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site | ||||||

| Sea Rim State Park | ||||||

| Seminole Canyon State Park & Historic Site | ||||||

| Sheldon Lake State Park & Environmental Learning Center | ||||||

| South Llano River State Park | ||||||

| Stephen F. Austin State Park | ||||||

| Tyler State Park | ||||||

| Village Creek State Park | ||||||

| Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site | ||||||

| Wyler Aerial Tramway | ||||||

| Zaragoza Birthplace State Historic Site | ||||||

| Source: Texas Parks and Wildlife, "State Parks" | ||||||

Economic activity on federal lands

Oil and gas activity

- See also: BLM oil and gas leases by state

Private mining companies, including oil and natural gas companies, can apply for leases from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to explore and produce energy on federal land. The company seeking a lease must nominate the land for oil and gas exploration to the BLM, which evaluates and approves the lease. The BLM state offices make leasing decisions based on their land use plans, which contain information on the land's resources and the potential environmental impact of oil or gas exploration. If federal lands are approved for leasing, the BLM requires information about how the company will conduct its drilling and production. Afterward, the BLM will produce an environmental analysis and a list of requirements before work on the land can begin. The agency also inspects the companies' drilling and production on the leased lands.[5]

In 2013, there were 47,427 active leases covering 36.09 million acres of federal land nationwide. Of that total, 683 leases (1.44 percent of all leases), covering 415,181 acres (1.15 percent of all leased land in 2013), were in Texas. In 2013, out of 3,770 new drilling leases approved nationwide by the BLM for oil and gas exploration, 965 leases (25.5 percent) were in Texas.[6][7][8][9][10]

The table below shows how Texas compared to neighboring states in oil and gas permits on BLM-managed lands in 2013. Texas had more active leases than Louisiana but fewer than New Mexico and Oklahoma. Texas had 415,181 acres under lease in 2013, which was more than Louisiana and Oklahoma but fewer than New Mexico.

| Oil and gas leasing on BLM lands by state | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Active permits on BLM lands (FY 2013) | Total acres under lease (FY 2013) | State percentage of total permits | State percentage of total acres |

| Texas | 683 | 415,181 | 1.44% | 1.15% |

| Louisiana | 525 | 297,028 | 1.11% | 0.82% |

| New Mexico | 8,348 | 4,819,205 | 17.60% | 13.35% |

| Oklahoma | 1,284 | 321,757 | 2.71% | 0.89% |

| Total United States | 47,427 permits | 36,092,482 acres | - | - |

| Source: U.S. Bureau of Land Management, "Oil and Gas Statistics" | ||||

Payments in lieu of taxes

- See also: Payments in lieu of taxes

Since local governments cannot collect taxes on federally owned property, the U.S. Department of the Interior issues payments to local governments to replace lost property tax revenue from federal land. The payments, known as "Payments in Lieu of Taxes" (PILTs), are typically used for funding services such as fire departments, police protection, school construction and roads.[11]

The table below shows PILTs for Texas compared to neighboring states between 2011 and 2013. Texas received more PILTs in 2013 than Louisiana and Oklahoma but fewer than New Mexico.

| Total PILTs for Texas and neighboring states | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | FY 2011 | FY 2012 | FY 2013 | State's percentage of 2013 total | ||

| Texas | $4,629,597 | $4,644,653 | $4,803,981 | 1.20% | ||

| Louisiana | $554,343 | $609,979 | $634,317 | 0.16% | ||

| New Mexico | $32,916,396 | $34,805,383 | $34,692,967 | 8.64% | ||

| Oklahoma | $2,639,362 | $2,740,199 | $2,794,607 | 0.70% | ||

| Source: U.S. Department of the Interior, "PILT" | ||||||

Legislation and regulation

Federal laws

Clean Air Act

The federal Clean Air Act requires each state to meet federal standards for air pollution. Under the act, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency oversees national air quality standards aimed at limiting pollutants from chemical plants, steel mills, utilities, and industrial factories. Individual states can enact stricter air standards if they choose, though each state must adhere to the EPA's minimum pollution standards. States implement federal air standards through a state implementation plan (SIP), which must be approved by the EPA.[12]

Clean Water Act

The federal Clean Water Act is meant to address and maintain the physical, chemical, and biological status of the waters of the United States. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates water pollution sources and provides financial assistance to states and municipalities for water quality programs.[13]

According to research done by The New York Times using annual averages from 2004 to 2007, Texas had 2,839 facilities that were regulated annually by the Clean Water Act. An average of 1,982.6 facilities violated the act annually from 2004 to 2007 in Texas, and the EPA enforced the act an average of 151.6 times a year in the state. This information, published by the Times in 2009, was the most recent information on the subject as of October 2014.[14]

The table below shows how Texas compared to neighboring states in The New York Times study, including the number of regulated facilities, facility violations, and the annual average of enforcement actions against regulated facilities between 2004 and 2007.

| The New York Times Clean Water Act study (2004-2007) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | Number of facilities regulated | Facility violations | Annual average enforcement actions |

| Texas | 2,839 | 1,982.6 | 151.6 |

| Louisiana | 1,580.5 | 368.9 | 93.4 |

| New Mexico | 126 | 72.2 | 9.8 |

| Oklahoma | 483.3 | 346.3 | 160.7 |

| Source: The New York Times, "Clean Water Act Violations: The Enforcement Record" | |||

Endangered Species Act

The federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973 provides for the identification, listing, and protection of both threatened and endangered species and their habitats. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the law was designed to prevent the extinction of vulnerable plant and animal species through the development of recovery plans and the protection of critical habitats. ESA administration and enforcement are the responsibility of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service.[15][16]

Federally listed species in Texas

There were 100 endangered and threatened animal and plant species believed to or known to occur in Texas as of July 2015.

The table below lists the 69 endangered and threatened animal species believed to or known to occur in the state. When an animal species has the word "Entire" after its name, that species will be found all throughout the state.[17]

| Endangered animal species in Texas | |

|---|---|

| Status | Species |

| Endangered | Amphipod, diminutive (Gammarus hyalleloides) |

| Endangered | Amphipod, Peck's cave (Stygobromus (=Stygonectes) pecki) |

| Endangered | Amphipod, Pecos (Gammarus pecos) |

| Endangered | Bat, Mexican long-nosed (Leptonycteris nivalis) |

| Threatened | Bear, Louisiana black (Ursus americanus luteolus) |

| Endangered | Beetle, [no common name] (Rhadine exilis) |

| Endangered | Beetle, [no common name] (Rhadine infernalis) |

| Endangered | Beetle, American burying (Nicrophorus americanus) |

| Endangered | Beetle, Coffin Cave mold (Batrisodes texanus) |

| Endangered | Beetle, Comal Springs dryopid (Stygoparnus comalensis) |

| Endangered | Beetle, Comal Springs riffle (Heterelmis comalensis) |

| Endangered | Beetle, Helotes mold (Batrisodes venyivi) |

| Endangered | Beetle, Kretschmarr Cave mold (Texamaurops reddelli) |

| Endangered | Beetle, Tooth Cave ground (Rhadine persephone) |

| Endangered | Crane, whooping (Grus americana) |

| Threatened | Cuckoo, yellow-billed (Coccyzus americanus) |

| Endangered | Curlew, Eskimo (Numenius borealis) |

| Endangered | Darter, fountain (Etheostoma fonticola) |

| Endangered | falcon, northern aplomado (Falco femoralis septentrionalis) |

| Endangered | Flycatcher, southwestern willow (Empidonax traillii extimus) |

| Endangered | Gambusia, Big Bend (Gambusia gaigei) |

| Endangered | Gambusia, Clear Creek (Gambusia heterochir) |

| Endangered | Gambusia, Pecos (Gambusia nobilis) |

| Endangered | Harvestman, Bee Creek Cave (Texella reddelli) |

| Endangered | Harvestman, Bone Cave (Texella reyesi) |

| Endangered | Harvestman, Cokendolpher Cave (Texella cokendolpheri) |

| Endangered | Jaguarundi (Herpailurus (=Felis) yagouaroundi cacomitli) |

| Threatened | Knot, red (Calidris canutus rufa) |

| Endangered | Manatee, West Indian (Trichechus manatus) |

| Endangered | Meshweaver, Braken Bat Cave (Cicurina venii) |

| Endangered | Meshweaver, Government Canyon Bat Cave (Cicurina vespera) |

| Endangered | Meshweaver, Madla's Cave (Cicurina madla) |

| Endangered | Meshweaver, Robber Baron Cave (Cicurina baronia) |

| Threatened | Minnow, Devils River (Dionda diaboli) |

| Endangered | Ocelot (Leopardus (=Felis) pardalis) |

| Threatened | Owl, Mexican spotted (Strix occidentalis lucida) |

| Threatened | Plover, piping except Great Lakes watershed (Charadrius melodus) |

| Endangered | Prairie-chicken, Attwater's greater (Tympanuchus cupido attwateri) |

| Threatened | Prairie-chicken, lesser (Tympanuchus pallidicinctus) |

| Endangered | Pseudoscorpion, Tooth Cave (Tartarocreagris texana) |

| Endangered | Pupfish, Comanche Springs (Cyprinodon elegans) |

| Endangered | Pupfish, Leon Springs (Cyprinodon bovinus) |

| Endangered | Salamander, Austin blind (Eurycea waterlooensis) |

| Endangered | Salamander, Barton Springs (Eurycea sosorum) |

| Threatened | Salamander, Georgetown (Eurycea naufragia) |

| Threatened | Salamander, Jollyville Plateau (Eurycea tonkawae) |

| Threatened | Salamander, Salado (Eurycea chisholmensis) |

| Threatened | Salamander, San Marcos (Eurycea nana) |

| Endangered | Salamander, Texas blind (Typhlomolge rathbuni) |

| Threatened | Sea turtle, green (Chelonia mydas) |

| Endangered | Sea turtle, hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) |

| Endangered | Sea turtle, Kemp's ridley (Lepidochelys kempii) |

| Endangered | Sea turtle, leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) |

| Threatened | Sea turtle, loggerhead (Caretta caretta) |

| Threatened | Shiner, Arkansas River Arkansas R. Basin (Notropis girardi) |

| Endangered | Shiner, sharpnose (Notropis oxyrhynchus) |

| Endangered | Shiner, smalleye (Notropis buccula) |

| Endangered | Snail, Pecos assiminea (Assiminea pecos) |

| Endangered | Spider, Government Canyon Bat Cave (Neoleptoneta microps) |

| Endangered | Spider, Tooth Cave (Leptoneta myopica) |

| Endangered | Springsnail, Phantom (Pyrgulopsis texana) |

| Endangered | Tern, least interior pop. (Sterna antillarum) |

| Endangered | Toad, Houston (Bufo houstonensis) |

| Endangered | Tryonia, Diamond (Pseudotryonia adamantina) |

| Endangered | Tryonia, Gonzales (Tryonia circumstriata (=stocktonensis)) |

| Endangered | Tryonia, Phantom (Tryonia cheatumi) |

| Endangered | Vireo, black-capped (Vireo atricapilla) |

| Endangered | Warbler (=wood), golden-cheeked (Dendroica chrysoparia) |

| Endangered | Woodpecker, red-cockaded (Picoides borealis) |

| Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Endangered and threatened species in Texas" | |

The table below lists the 31 endangered and threatened plant species believed to or known to occur in the state.[17]

| Endangered plant species in Texas | |

|---|---|

| Status | Species |

| Endangered | Ambrosia, south Texas (Ambrosia cheiranthifolia) |

| Endangered | Ayenia, Texas (Ayenia limitaris) |

| Endangered | Bladderpod, white (Lesquerella pallida) |

| Endangered | Bladderpod, Zapata (Lesquerella thamnophila) |

| Endangered | Cactus, black lace (Echinocereus reichenbachii var. albertii) |

| Threatened | Cactus, Chisos Mountain hedgehog (Echinocereus chisoensis var. chisoensis) |

| Threatened | Cactus, Lloyd's Mariposa (Echinomastus mariposensis) |

| Endangered | Cactus, Nellie cory (Coryphantha minima) |

| Endangered | Cactus, Sneed pincushion (Coryphantha sneedii var. sneedii) |

| Endangered | Cactus, star (Astrophytum asterias) |

| Endangered | cactus, Tobusch fishhook (Sclerocactus brevihamatus ssp. tobuschii) |

| Endangered | Cat's-eye, Terlingua Creek (Cryptantha crassipes) |

| Threatened | Cory cactus, bunched (Coryphantha ramillosa) |

| Endangered | Dawn-flower, Texas prairie (Hymenoxys texana) |

| Endangered | Dogweed, ashy (Thymophylla tephroleuca) |

| Endangered | Frankenia, Johnston's (Frankenia johnstonii) |

| Endangered | Gladecress, Texas golden (Leavenworthia texana) |

| Endangered | Ladies'-tresses, Navasota (Spiranthes parksii) |

| Endangered | Manioc, Walker's (Manihot walkerae) |

| Threatened | No common name (Geocarpon minimum) |

| Threatened | Oak, Hinckley (Quercus hinckleyi) |

| Endangered | Phlox, Texas trailing (Phlox nivalis ssp. texensis) |

| Endangered | Pitaya, Davis' green (Echinocereus viridiflorus var. davisii) |

| Endangered | Pondweed, Little Aguja (=Creek) (Potamogeton clystocarpus) |

| Endangered | Poppy-mallow, Texas (Callirhoe scabriuscula) |

| Threatened | Rose-mallow, Neches River (Hibiscus dasycalyx) |

| Endangered | Rush-pea, slender (Hoffmannseggia tenella) |

| Endangered | Sand-verbena, large-fruited (Abronia macrocarpa) |

| Endangered | Snowbells, Texas (Styrax texanus) |

| Threatened | Sunflower, Pecos (=puzzle, =paradox) (Helianthus paradoxus) |

| Endangered | Wild-rice, Texas (Zizania texana) |

| Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Endangered and threatened species in Texas" | |

State-listed species in Texas

Under Texas law, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department manages the state's list of endangered and threatened species. The full list can be found on the department's website.[18]

Enforcement

- See also: Enforcement at the EPA

Texas is part of the EPA's Region 6, which includes Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, and Oklahoma.[19]

The EPA enforces federal standards on air, water and hazardous chemicals. The EPA can engage in its own administrative action against private industries, or it can bring civil and/or criminal lawsuits against them. The goal of environmental law enforcement is usually the collection of penalties and fines for violations of laws like the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act. In 2013, the EPA estimated that 117.1 million pounds of pollution, which includes air pollution, water contaminants, and hazardous chemicals, were "reduced, treated or eliminated" and 61,289 cubic yards of soil and water were cleaned in Region 6. Additionally, 439 enforcement cases were initiated, and 443 enforcement cases were concluded in fiscal year 2013. In fiscal year 2012, the EPA collected $252 million in criminal fines and civil penalties from the private sector nationwide. In fiscal year 2013, the EPA collected $1.1 billion in criminal fines and civil penalties from the private sector nationwide, primarily due to the $1 billion settlement from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill along the Gulf Coast in 2010. The EPA only publishes nationwide data and does not provide state or region-specific information on the amount of fines and penalties it collects during a fiscal year.[20][21][22][23]

Mercury and air toxics standards

- See also: Mercury and air toxics standards

The EPA enforces mercury and air toxics standards (MATS), which are national limits on mercury, chromium, nickel, arsenic and acidic gases from coal- and oil-fired power plants. Power plants are required to have certain technologies to limit these pollutants. In December 2011, the EPA issued greater restrictions on the amount of mercury and other toxic pollutants produced by power plants. As of 2014, approximately 580 power plants, including 1,400 oil- and coal-fired electric-generating units, fell under the federal rule. The EPA has claimed that power plants account for 50 percent of mercury emissions, 75 percent of acidic gases and around 20 to 60 percent of toxic metal emissions in the United States. All coal- and oil-fired power plants with a capacity of 25 megawatts or greater are subject to the standards. The EPA has claimed that the standards will "prevent up to 1,200 premature deaths in Texas while creating up to $9.7 billion in health benefits in 2016."[24][25][26]

In 2014, the EPA released a study examining the economic, environmental, and health impacts of the MATS standards nationwide. Other organizations have released their own analyses about the effects of the MATS standards. Below is a summary of the studies on MATS and their effects as of November 2014.

EPA study

In 2014, the EPA argued that its MATS rule would prevent roughly 11,000 premature deaths and 130,000 asthma attacks nationwide. The agency also anticipated between $37 billion and $90 billion in "improved air quality benefits" annually. For the rule's cost, the EPA estimated that annual compliance fees for coal- and oil-fired power plants would reach $9.6 billion.[27]

NERA study

A 2012 study published by NERA Economic Consulting, a global consultancy group, reported that annual compliance costs in the electricity sector would total $10 billion in 2015 and nearly $100 billion cumulatively up through 2034. The same study found that the net impact of the MATS rule in 2015 would be the income equivalent of 180,000 fewer jobs. This net impact took into account the job gains associated with the building and refitting of power plants with new technology.[28]

Superfund sites

The EPA established the Superfund program as part of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act of 1980.The Superfund program focuses on uncontrolled or abandoned hazardous waste sites nationwide. The EPA inspects waste sites and establishes cleanup plans for them. The federal government can compel the private entities responsible for a waste site to clean the site or face penalties. If the federal government cleans a waste site, it can force the responsible party to reimburse the EPA or other federal agencies for the cleanup's cost. Superfund sites include oil refineries, smelting facilities, mines and other industrial areas. As of October 2014, there were 1,322 Superfund sites nationwide. A total of 91 Superfund sites reside in Region 6, with an average of 18.2 sites per state. There were 50 Superfund sites in Texas as of October 2014.[29][30]

Economic impact

| EPA studies |

|---|

| The Environmental Protection Agency publishes studies to evaluate the impact and benefits of its policies. Other studies may dispute the agency's findings or state the costs of its policies. |

According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), an independent federal agency, the Superfund program received an average of almost $1.2 billion annually in appropriated funds between the years 1981 and 2009, adjusted for inflation. The GAO estimated that the trust fund of the Superfund program decreased from $5 billion in 1997 to $137 million in 2009. The Superfund program received an additional $600 million in federal funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, also known as the stimulus bill.[31]

In March 2011, the EPA claimed that the agency's Superfund program produced economic benefits nationwide. Because Superfund sites are added and removed from a prioritized list on a regular basis, the total number of Superfund sites since the program's inception in 1980 is unknown. Based on a selective study of 373 Superfund sites cleaned up since the program's inception, the EPA estimated these economic benefits include the creation of 2,240 private businesses, $32.6 billion in annual sales from new businesses, 70,144 jobs and $4.9 billion in annual employment income.[32]

Other studies were published detailing the costs associated with the Superfund program. According to the Property and Environment Research Center, a free market-oriented policy group based in Montana, the EPA spent over $35 billion on the Superfund program between 1980 and 2005.[33][34]

Environmental impact

In March 2011, the EPA claimed that the Superfund program resulted in healthier environments surrounding former waste sites. An agency study analyzed the program's health and ecological benefits and focused on former landfills, mining areas, and abandoned dumps that were cleaned up and renovated. As of January 2009, out of the approximately 500 former Superfund sites used for the study, roughly 10 percent became recreational or commercial sites. Other former Superfund sites in the study are now used as wetlands, meadows, streams, scenic trails, parks, and habitats for plants and animals.[35]

Carbon emissions

- See also: Climate change, Greenhouse gas and Greenhouse gas emissions by state

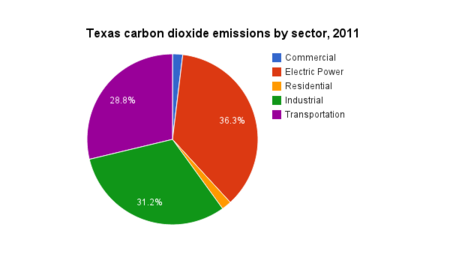

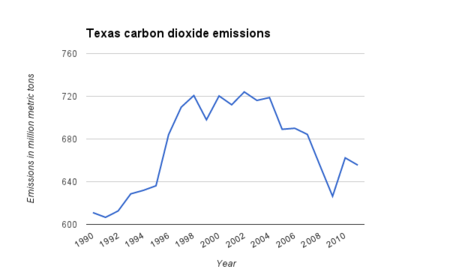

In 2011, Texas ranked 1st nationwide in carbon emissions and emitted more CO2 between 1990 and 2011 than any other state. In 2011, Texas emitted more greenhouse gases than California and Pennsylvania (the second and third ranked states) combined. Emissions rose sharply in Texas between 1995 and 1999 and peaked in 2002 when the state emitted 724 million metric tons of CO2. Since 2002, emissions in the state have declined.[36]

Carbon dioxide emissions in Texas (in million metric tons). Data was compiled by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. |

Pollution from energy use

Pollution from energy use includes three common air pollutants: carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and ozone. These and other pollutants are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) through the National Ambient Air Quality Standards, which are federal standards limiting pollutants that can harm human health in significant concentrations. Carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, is also regulated by the EPA, but it is excluded here since it is not one of the pollutants originally regulated under the Clean Air Act for its harm to human health.

Industries and motor vehicles emit carbon monoxide directly when they use energy. Nitrogen dioxide forms from the emissions of automobiles, power plants and other sources. Ground level ozone (also known as tropospheric ozone) is not emitted but is the product of chemical reactions between nitrogen dioxide and volatile organic chemicals. The EPA tracks these and other pollutants from monitoring sites across the United States. The data below shows nationwide and regional trends for carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and ozone between 2000 and 2014. States with consistent climates and weather patterns were grouped together by the EPA to make up each region.[37][38]

Carbon monoxide (CO)

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colorless, odorless gas produced from combustion processes, e.g., when gasoline reacts rapidly with oxygen and releases exhaust; the majority of national CO emissions come from mobile sources like automobiles. CO can reduce the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and at very high levels can cause death. CO concentrations are measured in parts per million (ppm). Since 1994, federal law prohibits CO concentrations from exceeding 9 ppm during an eight-hour period more than once per year.[39][40]

The chart below compares the annual average concentration of carbon monoxide (CO) in the Southern and Southwestern regions of the United States between 2000 and 2014. Carbon monoxide concentrations are measured in parts per million (ppm). States with consistent climates and weather patterns were grouped together by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which collects these data, to make up each region. Each line represents the annual average of all the data collected from pollution monitoring sites in each region. In the South, there were 18 monitoring sites throughout six states. In the Southwest, there were 24 monitoring sites throughout four states. In 2000, the average concentration of carbon monoxide was 3.84 ppm in the South, compared to 4.05 ppm in the Southwest. In 2014, the average concentration of carbon monoxide was 1.28 ppm in the South, a decrease of 66.6 percent from 2000, compared to 1.63 ppm in the Southwest, a decrease of 59.9 percent from 2000.[41]

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2)

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is one of a group of gasses known as nitrogen oxides (NOx). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) measures NO2 as a representative for the larger group of nitrogen oxides. NO2 forms from the emissions of cars, buses, trucks, power plants, and off-road equipment. It helps form ground-level ozone and fine particle pollution, and has been linked to respiratory problems. Since 1971, federal law prohibits NO2 concentrations from exceeding a daily one-hour average of 100 parts per billion (ppb) and an annual average of 53 parts per billion (ppb).[40][42][40]

The chart below compares the annual one-hour average concentration of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) in the Southern and Southwestern regions of the United States between 2000 and 2014. In the South, there were 34 monitoring sites throughout six states, compared to 10 monitoring sites throughout four states in the Southwest. In 2000, the one-hour daily average concentration of NO2 was 50.24 ppb in the South, compared to 71.5 ppb in the Southwest. In 2014, the one-hour daily average concentration of NO2 was 36.77 ppb in the South, a decrease of 26.8 percent since 2000, compared to 49.35 ppb in the Southwest, a decrease of 30.9 percent since 2000.[43]

Ground-level ozone

Ground-level ozone is created by chemical reactions between nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in sunlight. Major sources of NOx and VOCs include industrial facilities, electric utilities, automobiles, gasoline vapors, and chemical solvents. Ground-level ozone can produce health problems for children, the elderly, and asthmatics. Since 2008, federal law has prohibited ozone concentrations from exceeding a daily eight-hour average of 75 parts per billion (ppb). Beginning in 2025, federal law will prohibit ground-level ozone concentrations from exceeding a daily eight-hour average of 70 ppb.[40][44]

The chart below compares the daily eight-hour average concentration of ground-level ozone in the Southern and Southwestern regions of the United States between 2000 and 2014. In the chart below, ozone concentrations are measured in parts per million (ppm), which can be converted to parts per billion (ppb). In the South, there were 110 monitoring sites throughout six states, compared to 63 monitoring sites throughout four states in the Southeast. In 2000, the daily eight-hour average concentration of ozone was 0.0873 ppm, or 87.3 ppb in the South, compared to 0.0773 ppm, or 77.3 ppb in the Southwest. In 2014, the daily eight-hour average concentration of ozone was 0.0661 ppm, or 66.1 ppb in the South, a decrease of 24.2 percent since 2000, compared to 0.0692 ppm, or 69.2 ppb in the Southwest, a decrease of 10.5 percent since 2000.[45]

State laws

- The Irrigation Act (1913) created the Texas Board of Water Engineers, one of the state's first environmental quality agencies, which had the authority to determine surface water rights.[46]

- The Texas Pollution Control Act (1961) established the Texas Water Pollution Board, the state's first pollution control agency.[46]

- In 1917, Texas passed a constitutional amendment authorizing the conservation and development of the state's natural resources. The amendment allowed individual districts in the state to issue bonds and collect taxes for conservation and natural resource programs.[46][47]

- The Injection Well Act (1961) authorized the Texas Board of Water Engineers to manage waste disposal unrelated to the state's oil and gas industry. The board used injection wells to discharge waste to the surface so it could be removed.[46]

- The Texas Clean Air Act (1965) was passed two years after Congress passed the federal Clean Air Act. The Texas law established the Texas Air Control Board, which was responsible for monitoring and regulating air pollution. The board issued its first air quality standards in 1967.[46]

- The Texas Water Quality Act (1967) was passed five years before the federal Clean Water Act in 1972. The law created the Texas Water Quality Board, which replaced the Texas Water Pollution Control Board.[46]

- The Texas Solid Waste Disposal Act (1969) authorized the Texas Water Quality Board to regulate industrial solid waste and authorized the Texas Department of Health to regulate municipal solid waste.[46]

- The Texas Radiation Control Act (1989) authorized the Texas Department of Health to require licenses for the disposal of radioactive waste.[46]

Enforcement

Texas's Commission on Environmental Quality has the following major divisions:[48]

- The Office of Air regulates and maintains air quality throughout the state.[49]

- The Office of Waste regulates waste products from heavy industrial sources, including petroleum refineries and municipal buildings.[50]

- The Office of Water oversees drinking water quality, natural water sources and wastewater treatment.[51]

- The Office of Compliance and Enforcement monitors private facilities and municipalities for compliance with state environmental policies.[52]

Historical budget information

The table below shows state budget figures for Texas' environmental and natural resource departments compared to neighboring states.

| Total state natural resource expenditures by state | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Departments/Divisions | FY 2013 | FY 2012 | FY 2011 |

| Texas | Commission on Environmental Quality | $340,636,918 | $351,391,149 | $472,774,096 |

| Louisiana | Environmental Quality | $123,424,785 | $127,106,901 | $133,898,870 |

| New Mexico | Environment; Natural Resources | $69,594,000 | $79,682,500 | $74,085,200 |

| Oklahoma | Environmental Quality; Water Resources | $13,057,644 | $13,134,153 | $13,825,424 |

| Sources: Texas Legislative Budget Board, Louisiana Division of Administration, Office of the Governor of New Mexico, Oklahoma Office of Management and Enterprise Services | ||||

Major groups

Below is a list of environmental advocacy organizations in Texas.[53]

- Ecology Action of Texas

- Fort Worth Audubon Society

- Franklin Mountains Wilderness Coalition

- Friends of Anahuac Refuge

- Galveston Bay Foundation

- Native Plant Society of Texas

- Native Prairies Association of Texas

- Nature Conservancy - Texas

- Texas Parks and Wildlife Foundation

- San Marcos River Foundation

- Sierra Club - Lone Star Chapter

- Solar San Antonio

- Texas Campaign for the Environment

- Texas Environmental Center

Ballot measures

| Voting on the Environment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Ballot Measures | ||||

| By state | ||||

| By year | ||||

| Not on ballot | ||||

|

Below is a list of ballot measures relating to environmental issues in Texas.

- Texas Proposition 2, Tax Exemptions for Pollution Control Property Amendment (1993)

- Texas Proposition 2, Conservation and Reclamation District Amendment (1964)

- Texas Proposition 6, Tax Exemptions for Pollution Mitigation Equipment Amendment (1968)

- Texas Proposition 23, Water Development Bonds Amendment (1987)

- Texas Proposition 3, Tax Exemptions for Water Conservation Amendment (1997)

- Texas Proposition 7, Water Development Board Bond Authorizations Amendment (1997)

- Texas Proposition 19, Water Development Bonds Amendment (2001)

- Texas Proposition 1, Irrigation Districts Amendment (August 1897)

- Texas Proposition 1, Irrigation Districts Amendment (1900)

- Texas Proposition 2, Water Development Fund Amendment (1957)

- Texas Proposition 4, Water Storage Facilities Amendment (1962)

- Texas Proposition 11, Texas Water Development Amendment (1966)

- Texas Proposition 2, Water Development Fund Amendment (August 1969)

Denton fracking ban

The City of Denton approved a ballot initiative on November 4, 2014, banning fracking in the city. Denton, which was home to 121,000 residents and featured more than 270 natural gas wells in 2014, became the first major city in Texas to prohibit fracking within its city limits. The measure was never enforced, and by June 17, 2015, the Denton City Council had repealed the initiative. The repeal came after a bill was signed into law by Governor Greg Abbott (R) that prohibited cities from banning fracking.[54][55]

Read more about fate of the fracking ban here.

Recent news

The link below is to the most recent stories in a Google news search for the terms Texas environmental policy. These results are automatically generated from Google. Ballotpedia does not curate or endorse these articles.

See also

- Endangered species in Texas

- Energy policy in Texas

- Federal land ownership by state

- BLM oil and gas leases by state

- Payments in lieu of taxes

External links

- Texas Commission on Environmental Quality

- Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Congressional Research Service, "Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data," accessed September 15, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Congressional Research Service, "Federal Lands and Natural Resources: Overview and Selected Issues for the 113th Congress," December 8, 2014

- ↑ U.S. National Park Service, "2013 National Park Visitor Spending Effects Report," accessed October 14, 2014

- ↑ Texas Parks and Wildlife, "All State Parks," accessed November 19, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of Land Management, "Oil and Gas Lease Sales," accessed October 20, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of Land Management, "Number of Acres Leased During the Fiscal Year," accessed October 20, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of Land Management, "Total Number of Leases in Effect," accessed October 20, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of Land Management, "Summary of Onshore Oil and Gas Statistics," accessed October 20, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of Land Management, "Number of Drilling Permits Approved by Fiscal Year on Federal Lands," accessed October 20, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of Land Management, "Total Number of Acres Under Lease As of the Last Day of the Fiscal Year," accessed October 22, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Department of the Interior, "PILT," accessed October 4, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Understanding the Clean Air Act," accessed September 12, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Clean Water Act (CWA) Overview," accessed September 19, 2014

- ↑ The New York Times, "Clean Water Act Violations: The Enforcement Record," September 13, 2009

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Improving ESA Implementation," accessed May 15, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "ESA Overview," accessed October 1, 2014

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Endangered and threatened species in Texas," accessed July 6, 2015

- ↑ Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, "Nongame and Rare Species Program: Federal and State Listed Species," accessed August 4, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "EPA Region 6 (South Central)," accessed November 13, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Annual EPA Enforcement Results Highlight Focus on Major Environmental Violations," February 7, 2014

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency, "Accomplishments by EPA Region (2013)," May 12, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Enforcement Annual Results for Fiscal Year 2012," accessed October 1, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "EPA Enforcement in 2012 Protects Communities From Harmful Pollution," December 17, 2012

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Basic Information on Mercury and Air Toxics Standards," accessed January 5, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Cleaner Power Plants," accessed January 5, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Mercury and Air Toxics Standards in Texas," accessed September 9, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Benefits and Costs of Cleaning Up Toxic Air Pollution from Power Plants," accessed October 9, 2014

- ↑ NERA Economic Consulting, "An Economic Impact Analysis of EPA's Mercury and Air Toxics Standards Rule," March 1, 2012

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "What is Superfund?" accessed September 9, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "National Priorities List (NPL) of Superfund Sites," accessed October 7, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Government Accountability Office, "EPA's Estimated Costs to Remediate Existing Sites Exceed Current Funding Levels, and More Sites Are Expected to Be Added to the National Priorities List," accessed October 7, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Estimate of National Economic Impacts of Superfund Sites," accessed September 12, 2014

- ↑ Property and Environment Research Center, "Superfund Follies, Part II," accessed October 7, 2014

- ↑ Property and Environment Research Center, "Superfund: The Shortcut That Failed (1996)," accessed October 7, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Beneficial Effects of the Superfund Program," accessed September 12, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Energy Information Administration, "State Profiles and Energy Estimates," accessed October 13, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Air Trends," accessed October 30, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Basic Information - Ozone," accessed January 1, 2016

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Carbon Monoxide," accessed October 26, 2015

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS)," accessed October 26, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Regional Trends in CO Levels," accessed October 23, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Nitrogen dioxide," accessed October 26, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Regional Trends in Nitrogen Dioxide Levels," accessed October 23, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Ground Level Ozone," accessed October 26, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Regional Trends in Ozone Levels ," accessed October 26, 2015

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 46.5 46.6 46.7 Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, "History of the TCEQ and Its Predecessor Agencies," accessed November 14, 2014

- ↑ Texas Legislative Council, "Amendments to the Texas Constitution Since 1876," accessed November 14, 2014

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedEQcom - ↑ Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, "Air Division," accessed November 14, 2014

- ↑ Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, "Office of Waste," accessed November 14, 2014

- ↑ Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, "Office of Water," accessed November 14, 2014

- ↑ Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, "Office of Compliance and Enforcement," accessed November 14, 2014

- ↑ Eco-USA.net, "Texas Environmental Organizations," accessed November 14, 2014

- ↑ Denton Record Chronicle, "Group seeks ban on fracking," February 18, 2014

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedban