Review of ballot measure law changes in 2015: Four states remove local authority over contentious issues

December 30, 2015

By Josh Altic

As of December 27, 2015, Ballotpedia was covering 153 bills concerning initiatives, veto referendums and recalls that were proposed or reconsidered during the 2015 legislative sessions of 41 states. Of the total, 26 were approved, 57 were defeated or abandoned, and 70 were carried over to 2016. Most of the bills—147—were introduced this year, and the other six were carried over from the 2014 legislative session in New Jersey. These laws concerned everything from campaign finance reform and signature gatherer restrictions to signature requirements and subject restrictions.

Twenty-six states offer their residents some form of the power of statewide initiative or veto referendum. Non-I&R states that featured bills proposing to establish the powers of initiative and referendum at the statewide level this year included Alabama, Louisiana, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, West Virginia and Virginia. Moreover, a proposed legislatively referred constitutional amendment in Illinois was designed to remove a severe subject restriction on state initiatives; it would have changed the process from a largely unused power with a narrow scope to a potentially important and influential facet of Illinois politics. None of these bills were enacted, however.

Of the bills that were approved, 10 imposed additional restrictions on the petition process, and two lifted previously enacted restrictions. Some of the other 14 bills may have made signature petition processes easier or harder indirectly. For information on all the bills covered by Ballotpedia, see this page.

The charts below show outcome statistics for ballot law bills in 2015 and a breakdown of the laws that were approved.

|

|

|

Four states restrict scope of local ballot measures

Many activists have turned to local ballot measures to push agendas such as bans on genetically modified organisms (GMOs), higher minimum wages, LGBT anti-discrimination ordinances, marijuana legalization and anti-fracking restrictions. In some states, opposition to local ballot measures concerning these issues has been shown by officials at the state level, and conflict between the authority of local government entities and state governments has become an important narrative in U.S. politics. This narrative was brought into sharp relief in Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas and Arkansas this year, as state lawmakers in these states made explicit prohibitions against local laws concerning contentious issues.

Ban on minimum wage increases - Missouri

- See also: Missouri House Bill 722 (2015)

Missouri House Bill 722 prohibited any local law imposing a minimum wage higher than the state-set minimum wage. This law was an important element behind the Kansas City attorney removing two minimum wage-related ballot items from the Kansas City ballot for the election on November 3, 2015.

Ban on LGBT anti-discrimination ordinances - Arkansas

- See also: Arkansas Senate Bill 202 (2015)

Arkansas Senate Bill 202, known as Act 137 after it was enacted, prohibited local laws creating a protected class or prohibiting discrimination based on characteristics not recognized by state law. The key issue at stake was the validity of local ordinances protecting lesbian, gay and transgender individuals from discrimination.

Senate Bill 202 was approved in the Arkansas State Senate on February 9, 2015, by a vote of 24-8. In the Arkansas House of Representatives, the bill was approved on February 13, 2015. Both votes were completed largely along party lines, without any Republicans voting "no" and with only a few Democrats voting "yes." Gov. Asa Hutchinson (R) allowed the law to go into effect without signing it.[1]

Voters in Fayetteville approved an LGBT anti-discrimination ordinance in September 2015. As of December 2015, it was known that the following Arkansas cities and county had enacted laws protecting against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity:

The sponsor of SB 202, as well as other supporters, said the bill made any previously approved LGBT anti-discrimination ordinance void. But the legal counsel for several cities with such ordinances argued that the bill had no effect on local LGBT-related ordinances. Little Rock City Attorney Tom Carpenter said, “They’re not in conflict. There’s nothing mentioned in the city’s ordinance that’s not already protected under state law.” Carpenter claimed that, although the state's civil rights law does not mention sexual orientation or gender identity, the state does have some anti-bullying laws, homeless shelter laws and other laws that explicitly recognize and protect members of the LGBT community. Other city attorneys agreed with Tom Carpenter's interpretation.[2]

Sen. Hester, the sponsor of SB 202, disagreed, saying, “I think their ordinances are null and void. I think that’s very clear.”[2]

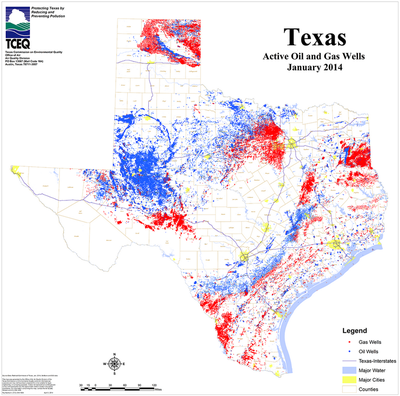

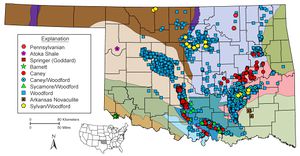

Ban on local anti-fracking laws - Texas and Oklahoma

- See also: Texas House Bill 40 (2015) and Oklahoma Senate Bill 809 (2015)

Restrictions on the oil and gas industry, especially with regard to fracking, played a prominent role in the debate over state control versus local control. Early in 2015, Texas lawmakers passed House Bill 40, which was designed to give exclusive jurisdiction

over the oil and gas industry to the state government, prohibiting local oil and gas-related ordinances, initiatives and regulations. The law was, in part, a response to an anti-fracking initiative approved in Denton in November 2014. Soon after the enactment of HB 40, the Denton City Council rescinded the anti-fracking initiative in order to comply with the state law.

Todd Staples, president of the Texas Oil & Gas Association, approved of HB 40 and said it would protect the state's economy and provide proper industry governance by allowing uniform regulation at the state level.

Opponents of House Bill 40 argued that it was the result of lobbying and monetary contributions from the oil and gas industry—especially Dan and Farris Wilks, who owned a company called Frac Tech until 2011—to Texan politicians.[3]

Jesse Coleman, a Greenpeace USA researcher, said, “Here you have the crux of democracy in Denton, Texas, where people got together and voted on what they wanted. And now the same industry that is saying that the federal government can’t regulate them, is saying that, no, even on the local level, they can’t regulate them because they don’t want any regulation at all.”[3]

Referring to efforts to prevent local restrictions on oil and gas extraction by the oil and gas industry in other states, Coleman also said, "The [fracking] industry’s strategy is to silence criticism on a local level and to prevent recourse for local people. This is something they’re pursuing in all of the states where drilling is a big deal. They’re pursuing the strategy of taking away the rights of citizens of small towns from determining whether they want fracking.”[3]

A law similar to Texas House Bill 40 was approved in Oklahoma. Senate Bill 809, which also gave authority over the oil and gas industry to the state government, was approved largely along party lines, with all of the Democratic representatives voting "no" and only one Democrat voting "yes" in the state Senate.

In Colorado, anti-fracking activists decried Colorado House Bill 15-1057 as an attempt to prevent anti-oil and gas industry initiatives, specifically a proposed statewide initiative designed to give a right to local control over the oil and gas industry. HB 15-1057 requires a state-provided fiscal impact statement to appear on initiative petition sheets during circulation. Supporters of the bill said it was designed to give voters more information about proposed initiatives before signing petitions. Opponents argued that showing the fiscal impact of an initiative challenging state control over fracking while not showing a summary of the other aspects of the issue, such as effects on the environment and on health, could deter voters from signing a petition.[4]

Cecelia Gilboy, writing for Boulder Weekly, summarized the position of this particular set of HB 1057 critics:

| “ |

When it comes to the oil and gas industry, those who oppose HB 1057 believe that the state will intentionally be creating a one-sided message in order to pacify the industry and thwart initiatives that could hurt its bottom line. For instance, a cost analysis note on local control over drilling operations would not include any analysis of benefits to air, water, human health, tourism, property values or quality of life, even though several of these categories could create greater positive economic impact to the people of Colorado than any revenue that will ever be generated by the oil and gas industry.[5] |

” |

| —Cecilia Gilboy[4] | ||

Nebraska lawmakers lift state's seven-year-old initiative restriction

- See also: Nebraska Legislative Bill 367 (2015) and pay-per-signature

Nebraska Legislative Bill 367 was introduced on January 15, 2015, by Sen. Mike Groene (R-42), who designed the bill to eliminate the state's seven-year-old ban on paying signature petition circulators based on the number of signatures they collect. The state's unicameral legislature unanimously voted to approve the bill, and Gov. Pete Ricketts (R) signed it into law on April 13, 2015.[6][7]

Sen. Groene said that the state lawmakers had been engaged in a "civil war" with the voters ever since voters passed term limits on the legislature. He said that the ban on paying signature gatherers according to signatures collected made initiative petitions much more expensive and had “really broken the back of people trying to take part in their government through the petition process.” Groene, who made this bill one of his priorities in his first term in the state Senate, said, “It’s time for this body to call a truce.”[7]

Sen. Paul Schumacher (R-22), who also supported LB 367, condemned the bill that first imposed the circulator pay restrictions in 2008 as “reflective of a government that was afraid of its people.”[7]

Ohio legislators and voters approve restriction against "monopoly initiatives"

- See also: Ohio House Joint Resolution 4 (2015)

Ohio lawmakers passed Ohio House Joint Resolution 4, which went on the November 2015 ballot as Issue 2, as a way to invalidate the Marijuana Legalization Initiative, Issue 3. Issue 3 would have created 10 facilities with exclusive rights to commercially grow cannabis if it had been approved. Issue 2 created provisions restricting initiatives seen by state officials to enact a monopoly or special privilege.[8][1]

Under Issue 2, the Ohio Ballot Board regulates initiatives concerning monopolies.

If the board decides an initiative certified for the ballot creates an economic monopoly or special privilege for any nonpublic entity—including individuals, corporations and organizations—then two questions must appear on the ballot for that initiative.

The first question must ask, "Shall the petitioner, in violation of division (B)(1) of Section 1e of Article II of the Ohio Constitution, be authorized to initiate a constitutional amendment that grants or creates a monopoly, oligopoly, or cartel, specifies or determines a tax rate, or confers a commercial interest, commercial right, or commercial license that is not available to other similarly situated persons?" The second question must provide a summary of the proposed initiative and ask voters if they wish to approve it. Both questions must receive majority approval for the initiative to be enacted.

For more details, see Ballotpedia's pages on Issue 2 and Issue 3.

Residency restrictions tightened in Maine

Maine Legislative Document 176 added the following restrictions to the petition process in the state:[1]

- It prohibited nonresidents from collecting signatures or handling signature petitions in any way.

- It required any paid workers for initiative, referendum or recall petition campaigns to register with the state's Commission on Governmental Ethics and Election Practices and display a badge disclosing their status as a paid circulator while gathering signatures.

- it required any committee or organization behind a petition to post a bond with the state in the amount of $2,000 for every circulator who receives more than $2,500 in payment.

Maine legislators passed Maine Legislative Document 176 to prevent a system previously used in some signature gathering campaigns, including the signature campaign for Question 1, a bear hunting measure decided in 2014. This system involved an out-of-state signature gatherer paired up with an in-state witness to comply with Maine's prior resident "witness" requirement. The campaign behind the Maine bear hunting initiative paid PCI Consulting, a signature gathering firm from California, to help circulate its petition. PCI Consulting used an in-state witness to qualify the bear hunting initiative for the ballot. Supporters of LD 176 said that this system allowed abuse since there was no way to verify that all signatures were, in fact, witnessed by a Maine resident.[9][1]

California lawmakers make proposing an initiative 10 times more expensive

- See also: California Assembly Bill 1100 (2015)

California Assembly Bill 1100 increased the initial filing fee to start the ballot initiative process from $200 to $2,000. This refundable deposit would be returned if a proposed initiative reached the ballot.[10]

Assembly members Evan Low (D-28) and Richard Bloom (D-50), as well as other supporters of the bill, said it would prevent proposals that were unlikely to generate enough support to make the ballot from being filed as initiatives. Supporters of AB 1100 said it would put up a road block against misguided, frivolous and ridiculous initiatives. They pointed to the “Sodomite Suppression” Initiative, to which AB 1100 was a response, as an example, arguing that if the initiative's sponsor had been required to pay $2,000 instead of just $200, the initiative would probably never have been filed.[10][11]

Opponents of the bill said it was an overreaction to one radical and ridiculous proposal. They also argued that AB 1100 would discourage citizens with important and serious ideas from using the state's initiative process.[11]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Open States, "House Joint Resolution 4 (2015)," accessed December 21, 2015 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Open" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 2.0 2.1 Arkansas News, "New law seeks to bar anti-discrimination ordinances, but interpretations vary," July 22, 2015

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 RH Reality Check, "Local Control? Texas Fracking Billionaires Say ‘Not So Fast,’" June 2, 2015

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Boulder Weekly, "With the passage of HB 1057, have Democrats once again killed your right to vote on fracking, this time in 2016?" May 21, 2015

- ↑ Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ Open States, "Nebraska Legislative Bill 367 (2015)," accessed April 23, 2015

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Citizens in Charge, "Nebraska Repeals Pay Ban, Not a Dissenting Vote," April 7, 2015

- ↑ The Plain Dealer, "Lawmakers propose constitutional amendment that could block marijuana legalization effort," June 16, 2015

- ↑ centralmaine.com, "Bill closes loophole in signature gathering process," March 10, 2015

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 LegiScan, "Assembly Bill 1100 (2015)," accessed September 11, 2015

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Orange County Register, "Preserve state initiative process," April 9, 2015

| |||||