Federal environmental regulation in Florida

![]() This article does not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

This article does not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

![]() This article does not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

This article does not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

| Public Policy |

|---|

|

Federal environmental regulation involves the implementation of federal environmental laws, such as the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is primarily responsible for enforcing federal air and water quality standards; the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is primarily responsible for managing endangered species. State government agencies will often share enforcement responsibilities with the EPA on issues such as air pollution, water pollution, hazardous waste, and other environmental issues.[1]

Legislation and regulation

Federal laws

Clean Air Act

The federal Clean Air Act requires each state to meet federal standards for air pollution. Under the act, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency oversees national air quality standards aimed at limiting pollutants from chemical plants, steel mills, utilities, and industrial factories. Individual states can enact stricter air standards if they choose, though each state must adhere to the EPA's minimum pollution standards. States implement federal air standards through a state implementation plan (SIP), which must be approved by the EPA.[2]

Clean Water Act

The federal Clean Water Act is meant to address and maintain the physical, chemical, and biological status of the waters of the United States. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates water pollution sources and provides financial assistance to states and municipalities for water quality programs.[3]

According to research done by The New York Times using annual averages from 2004 to 2007, Florida had 477.5 facilities that were regulated annually by the Clean Water Act. An average of 133.8 facilities violated the act annually from 2004 to 2007 in Florida, and the EPA enforced the act an average of 57.1 times a year in the state. This information, published by the Times in 2009, was the most recent information on the subject as of October 2014.[4]

The table below shows how Florida compared to neighboring states in The New York Times study, including the number of regulated facilities, facility violations, and the annual average of enforcement actions against regulated facilities between 2004 and 2007.

| The New York Times Clean Water Act study (2004-2007) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Number of facilities regulated | Facility violations | Annual average enforcement actions | |

| Florida | 477.5 | 133.8 | 57.1 | |

| Alabama | 1,588.30 | 663.3 | 67.1 | |

| Georgia | 1008.5 | 67.8 | 32.7 | |

| Louisiana | 1580.5 | 368.9 | 93.4 | |

| Source: The New York Times, "Clean Water Act Violations: The Enforcement Record" | ||||

Endangered Species Act

The federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973 provides for the identification, listing, and protection of both threatened and endangered species and their habitats. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the law was designed to prevent the extinction of vulnerable plant and animal species through the development of recovery plans and the protection of critical habitats. ESA administration and enforcement are the responsibility of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service.[5][6]

Federally listed species in Florida

There were 129 endangered and threatened animal and plant species believed to or known to occur in Florida as of July 2015.

The table below lists the 70 endangered and threatened animal species believed to or known to occur in the state. When an animal species has the word "Entire" after its name, that species will be found all throughout the state.[7]

| Endangered animal species in Florida | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status | Species | ||||||

| Threatened | Bankclimber, purple (mussel) (Elliptoideus sloatianus) | ||||||

| Endangered | bat, Florida bonneted (Eumops floridanus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Bat, gray Entire (Myotis grisescens) | ||||||

| Endangered | Bat, Indiana Entire (Myotis sodalis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Bean, Choctaw (Villosa choctawensis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Butterfly, Bartram's hairstreak (Strymon acis bartrami) | ||||||

| Endangered | Butterfly, Florida leafwing (Anaea troglodyta floridalis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Butterfly, Miami Blue (Cyclargus (=Hemiargus) thomasi bethunebakeri) | ||||||

| Endangered | Butterfly, Schaus swallowtail Entire (Heraclides aristodemus ponceanus) | ||||||

| Threatened | Caracara, Audubon's crested FL pop. (Polyborus plancus audubonii) | ||||||

| Threatened | Coral, elkhorn (Acropora palmata) | ||||||

| Threatened | Coral, staghorn (Acropora cervicornis) | ||||||

| Threatened | Crocodile, American FL pop. (Crocodylus acutus) | ||||||

| Threatened | Darter, Okaloosa Entire (Etheostoma okaloosae) | ||||||

| Endangered | Deer, key Entire (Odocoileus virginianus clavium) | ||||||

| Endangered | Ebonyshell, round (Fusconaia rotulata) | ||||||

| Endangered | Kidneyshell, southern (Ptychobranchus jonesi) | ||||||

| Endangered | Kite, Everglade snail FL pop. (Rostrhamus sociabilis plumbeus) | ||||||

| Threatened | Knot, red (Calidris canutus rufa) | ||||||

| Endangered | Manatee, West Indian Entire (Trichechus manatus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Moccasinshell, Gulf (Medionidus penicillatus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Moccasinshell, Ochlockonee (Medionidus simpsonianus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Mouse, Anastasia Island beach Entire (Peromyscus polionotus phasma) | ||||||

| Endangered | Mouse, Choctawhatchee beach Entire (Peromyscus polionotus allophrys) | ||||||

| Endangered | Mouse, Key Largo cotton Entire (Peromyscus gossypinus allapaticola) | ||||||

| Endangered | Mouse, Perdido Key beach Entire (Peromyscus polionotus trissyllepsis) | ||||||

| Threatened | Mouse, southeastern beach U.S.A.(FL) (Peromyscus polionotus niveiventris) | ||||||

| Endangered | Mouse, St. Andrew beach U.S.A.(FL) (Peromyscus polionotus peninsularis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Panther, Florida (Puma (=Felis) concolor coryi) | ||||||

| Threatened | Pigtoe, fuzzy (Pleurobema strodeanum) | ||||||

| Threatened | Pigtoe, narrow (Fusconaia escambia) | ||||||

| Endangered | Pigtoe, oval (Pleurobema pyriforme) | ||||||

| Threatened | Pigtoe, tapered (Fusconaia burkei) | ||||||

| Threatened | Plover, piping except Great Lakes watershed (Charadrius melodus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Pocketbook, shinyrayed (Lampsilis subangulata) | ||||||

| Endangered | Rabbit, Lower Keys marsh FL (Sylvilagus palustris hefneri) | ||||||

| Endangered | Rice rat lower FL Keys (Oryzomys palustris natator) | ||||||

| Threatened | Salamander, frosted flatwoods Entire (Ambystoma cingulatum) | ||||||

| Endangered | salamander, Reticulated flatwoods Entire (Ambystoma bishopi) | ||||||

| Threatened | sandshell, Southern (Hamiota australis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Sawfish, smalltooth United States DPS (Pristis pectinata) | ||||||

| Threatened | scrub-jay, Florida Entire (Aphelocoma coerulescens) | ||||||

| Endangered | Sea turtle, green FL, Mexico nesting pops. (Chelonia mydas) | ||||||

| Endangered | Sea turtle, hawksbill Entire (Eretmochelys imbricata) | ||||||

| Endangered | Sea turtle, Kemp's ridley Entire (Lepidochelys kempii) | ||||||

| Endangered | Sea turtle, leatherback Entire (Dermochelys coriacea) | ||||||

| Threatened | Sea turtle, loggerhead Northwest Atlantic Ocean DPS (Caretta caretta) | ||||||

| Threatened | Shrimp, Squirrel Chimney Cave Entire (Palaemonetes cummingi) | ||||||

| Threatened | Skink, bluetail mole Entire (Eumeces egregius lividus) | ||||||

| Threatened | Skink, sand Entire (Neoseps reynoldsi) | ||||||

| Threatened | Slabshell, Chipola (Elliptio chipolaensis) | ||||||

| Threatened | Snail, Stock Island tree Entire (Orthalicus reses (not incl. nesodryas)) | ||||||

| Threatened | Snake, Atlantic salt marsh Entire (Nerodia clarkii taeniata) | ||||||

| Threatened | Snake, eastern indigo Entire (Drymarchon corais couperi) | ||||||

| Endangered | Sparrow, Cape Sable seaside Entire (Ammodramus maritimus mirabilis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Sparrow, Florida grasshopper Entire (Ammodramus savannarum floridanus) | ||||||

| Threatened | Stork, wood AL, FL, GA, MS, NC, SC (Mycteria americana) | ||||||

| Threatened | Sturgeon (Gulf subspecies), Atlantic Entire (Acipenser oxyrinchus (=oxyrhynchus) desotoi) | ||||||

| Endangered | Sturgeon, shortnose Entire (Acipenser brevirostrum) | ||||||

| Threatened | Tern, roseate Western Hemisphere except NE U.S. (Sterna dougallii dougallii) | ||||||

| Endangered | Threeridge, fat (mussel) (Amblema neislerii) | ||||||

| Endangered | Vole, Florida salt marsh Entire (Microtus pennsylvanicus dukecampbelli) | ||||||

| Endangered | Warbler (=wood), Bachman's Entire (Vermivora bachmanii) | ||||||

| Endangered | Warbler, Kirtland's Entire (Setophaga kirtlandii (= Dendroica kirtlandii)) | ||||||

| Endangered | Whale, finback Entire (Balaenoptera physalus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Whale, humpback Entire (Megaptera novaeangliae) | ||||||

| Endangered | Whale, North Atlantic Right Entire (Eubalaena glacialis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Wolf, red except where EXPN (Canis rufus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Woodpecker, red-cockaded Entire (Picoides borealis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Woodrat, Key Largo Entire (Neotoma floridana smalli) | ||||||

| Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Endangered and threatened species in Florida" | |||||||

The table below lists the 59 endangered and threatened plant species believed to or known to occur in the state.[8]

| Endangered plant species in Florida | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status | Species | ||||||

| Endangered | Aster, Florida golden (Chrysopsis floridana) | ||||||

| Endangered | Beargrass, Britton's (Nolina brittoniana) | ||||||

| Endangered | Beauty, Harper's (Harperocallis flava) | ||||||

| Endangered | Bellflower, Brooksville (Campanula robinsiae) | ||||||

| Threatened | Birds-in-a-nest, white (Macbridea alba) | ||||||

| Endangered | Blazingstar, scrub (Liatris ohlingerae) | ||||||

| Threatened | Bonamia, Florida (Bonamia grandiflora) | ||||||

| Endangered | Brickell-bush, Florida (Brickellia mosieri) | ||||||

| Threatened | Buckwheat, scrub (Eriogonum longifolium var. gnaphalifolium) | ||||||

| Threatened | Butterwort, Godfrey's (Pinguicula ionantha) | ||||||

| Endangered | Cactus, Florida semaphore (Consolea corallicola) | ||||||

| Endangered | Cactus, Key tree (Pilosocereus robinii) | ||||||

| Endangered | Campion, fringed (Silene polypetala) | ||||||

| Endangered | Chaffseed, American (Schwalbea americana) | ||||||

| Endangered | Cladonia, Florida perforate (Cladonia perforata) | ||||||

| Endangered | Flax, Carter's small-flowered (Linum carteri carteri) | ||||||

| Endangered | Fringe-tree, pygmy (Chionanthus pygmaeus) | ||||||

| Threatened | Gooseberry, Miccosukee (Ribes echinellum) | ||||||

| Endangered | Gourd, Okeechobee (Cucurbita okeechobeensis ssp. okeechobeensis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Harebells, Avon Park (Crotalaria avonensis) | ||||||

| Endangered | Hypericum, highlands scrub (Hypericum cumulicola) | ||||||

| Endangered | Jacquemontia, beach (Jacquemontia reclinata) | ||||||

| Endangered | Lead-plant, Crenulate (Amorpha crenulata) | ||||||

| Endangered | Lupine, scrub (Lupinus aridorum) | ||||||

| Endangered | Meadowrue, Cooley's (Thalictrum cooleyi) | ||||||

| Endangered | Milkpea, Small's (Galactia smallii) | ||||||

| Endangered | Mint, Garrett's (Dicerandra christmanii) | ||||||

| Endangered | Mint, Lakela's (Dicerandra immaculata) | ||||||

| Endangered | Mint, longspurred (Dicerandra cornutissima) | ||||||

| Endangered | Mint, scrub (Dicerandra frutescens) | ||||||

| Endangered | Mustard, Carter's (Warea carteri) | ||||||

| Endangered | Pawpaw, beautiful (Deeringothamnus pulchellus) | ||||||

| Endangered | Pawpaw, four-petal (Asimina tetramera) | ||||||

| Endangered | Pawpaw, Rugel's (Deeringothamnus rugelii) | ||||||

| Threatened | Pigeon wings (Clitoria fragrans) | ||||||

| Endangered | Pinkroot, gentian (Spigelia gentianoides) | ||||||

| Endangered | Plum, scrub (Prunus geniculata) | ||||||

| Endangered | Polygala, Lewton's (Polygala lewtonii) | ||||||

| Endangered | Polygala, tiny (Polygala smallii) | ||||||

| Endangered | Prickly-apple, aboriginal (Harrisia (=Cereus) aboriginum (=gracilis)) | ||||||

| Endangered | Prickly-apple, fragrant (Cereus eriophorus var. fragrans) | ||||||

| Endangered | Rhododendron, Chapman (Rhododendron chapmanii) | ||||||

| Endangered | Rosemary, Apalachicola (Conradina glabra) | ||||||

| Endangered | Rosemary, Etonia (Conradina etonia) | ||||||

| Endangered | Rosemary, short-leaved (Conradina brevifolia) | ||||||

| Endangered | Sandlace (Polygonella myriophylla) | ||||||

| Threatened | Seagrass, Johnson's (Halophila johnsonii) | ||||||

| Threatened | Skullcap, Florida (Scutellaria floridana) | ||||||

| Endangered | Snakeroot (Eryngium cuneifolium) | ||||||

| Endangered | Spurge, deltoid (Chamaesyce deltoidea ssp. deltoidea) | ||||||

| Threatened | Spurge, Garber's (Chamaesyce garberi) | ||||||

| Threatened | Spurge, telephus (Euphorbia telephioides) | ||||||

| Endangered | Thoroughwort, Cape Sable (Chromolaena frustrata) | ||||||

| Endangered | Torreya, Florida (Torreya taxifolia) | ||||||

| Endangered | Warea, wide-leaf (Warea amplexifolia) | ||||||

| Endangered | Water-willow, Cooley's (Justicia cooleyi) | ||||||

| Threatened | Whitlow-wort, papery (Paronychia chartacea) | ||||||

| Endangered | Wireweed (Polygonella basiramia) | ||||||

| Endangered | Ziziphus, Florida (Ziziphus celata) | ||||||

| Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Endangered and threatened species in Florida" | |||||||

State-listed species in Florida

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWS) maintains the state's list of threatened species and "species of special concern." Florida law does not have a designation for "endangered" species; rather, Florida designates species as "threatened" if they are at risk of extinction. "Threatened" species under Florida's state list are all distinct from federally listed species. "Species of special concern" are species being studied and monitored by the state that have not received the designation of threatened.[9]

The table below shows the number of state-listed threatened species and species of special concern in Florida by status and species type. A complete list with the names and status of each species can be found here.

| State-listed animal species in Florida by status and type | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status | Fish | Amphibians | Reptiles | Birds | Mammals | Invertebrates | Total |

| Threatened | 3 | 0 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 19 |

| Special concern species | 6 | 4 | 6 | 16 | 6 | 4 | 42 |

| Total state-listed species | 9 | 4 | 13 | 21 | 9 | 5 | 61 |

| Source: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, "Florida's Endangered and Threatened Species (as of January 2013)" | |||||||

Enforcement

- See also: Enforcement at the EPA

Florida is part of the EPA's Region 4, which includes Kentucky, Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee.

The EPA enforces federal standards on air, water and hazardous chemicals. The EPA takes administrative action against violators of environmental laws, or brings civil and/or criminal lawsuits, often with the goal of collecting penalties/fines and demanding compliance with laws like the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act. In 2013, the EPA estimated that 42.8 million pounds of pollution, which includes air pollution, water contaminants, and hazardous chemicals, were "reduced, treated or eliminated" and 16.6 million cubic yards of soil and water were cleaned in Region 4. Additionally, 420 enforcement cases were initiated, and 416 enforcement cases were concluded in fiscal year 2013. In fiscal year 2012, the EPA collected $252 million in criminal fines and civil penalties from the private sector nationwide. In fiscal year 2013, the EPA collected $1.1 billion in criminal fines and civil penalties from the private sector nationwide, primarily due to the $1 billion settlement from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill along the Gulf Coast in 2010. The EPA only publishes nationwide data and does not provide state or region-specific information on the amount of fines and penalties it collects during a fiscal year.[10][11][12][13]

Mercury and air toxics standards

- See also: Mercury and air toxics standards

The EPA enforces mercury and air toxics standards (MATS), which are national limits on mercury, chromium, nickel, arsenic and acidic gases from coal- and oil-fired power plants. Power plants are required to have certain technologies to limit these pollutants. In December 2011, the EPA issued greater restrictions on the amount of mercury and other toxic pollutants produced by power plants. As of 2014, approximately 580 power plants, including 1,400 oil- and coal-fired electric-generating units, fell under the federal rule. The EPA has claimed that power plants account for 50 percent of mercury emissions, 75 percent of acidic gases and around 20 to 60 percent of toxic metal emissions in the United States. All coal- and oil-fired power plants with a capacity of 25 megawatts or greater are subject to the standards. The EPA has claimed that the standards will "prevent up to 730 premature deaths in Florida while creating up to $6 billion in health benefits in 2016."[14][15][16]

In 2014, the EPA released a study examining the economic, environmental, and health impacts of the MATS standards nationwide. Other organizations have released their own analyses about the effects of the MATS standards. Below is a summary of the studies on MATS and their effects as of November 2014.

EPA study

In 2014, the EPA argued that its MATS rule would prevent roughly 11,000 premature deaths and 130,000 asthma attacks nationwide. The agency also anticipated between $37 billion and $90 billion in "improved air quality benefits" annually. For the rule's cost, the EPA estimated that annual compliance fees for coal- and oil-fired power plants would reach $9.6 billion.[17]

NERA study

A 2012 study published by NERA Economic Consulting, a global consultancy group, reported that annual compliance costs in the electricity sector would total $10 billion in 2015 and nearly $100 billion cumulatively up through 2034. The same study found that the net impact of the MATS rule in 2015 would be the income equivalent of 180,000 fewer jobs. This net impact took into account the job gains associated with the building and refitting of power plants with new technology.[18]

Superfund sites

The EPA established the Superfund program as part of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act of 1980.The Superfund program focuses on uncontrolled or abandoned hazardous waste sites nationwide. The EPA inspects waste sites and establishes cleanup plans for them. The federal government can compel the private entities responsible for a waste site to clean the site or face penalties. If the federal government cleans a waste site, it can force the responsible party to reimburse the EPA or other federal agencies for the cleanup's cost. Superfund sites include oil refineries, smelting facilities, mines and other industrial areas. As of October 2014, there were 1,322 Superfund sites nationwide. A total of 186 Superfund sites reside in Region 4, with an average of 26.25 sites per state. There were 53 Superfund sites in Florida as of October 2014.[19][20]

Economic impact

| EPA studies |

|---|

| The Environmental Protection Agency publishes studies to evaluate the impact and benefits of its policies. Other studies may dispute the agency's findings or state the costs of its policies. |

According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), an independent federal agency, the Superfund program received an average of almost $1.2 billion annually in appropriated funds between the years 1981 and 2009, adjusted for inflation. The GAO estimated that the trust fund of the Superfund program decreased from $5 billion in 1997 to $137 million in 2009. The Superfund program received an additional $600 million in federal funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, also known as the stimulus bill.[21]

In March 2011, the EPA claimed that the agency's Superfund program produced economic benefits nationwide. Because Superfund sites are added and removed from a prioritized list on a regular basis, the total number of Superfund sites since the program's inception in 1980 is unknown. Based on a selective study of 373 Superfund sites cleaned up since the program's inception, the EPA estimated these economic benefits include the creation of 2,240 private businesses, $32.6 billion in annual sales from new businesses, 70,144 jobs and $4.9 billion in annual employment income.[22]

Other studies were published detailing the costs associated with the Superfund program. According to the Property and Environment Research Center, a free market-oriented policy group based in Montana, the EPA spent over $35 billion on the Superfund program between 1980 and 2005.[23][24]

Environmental impact

In March 2011, the EPA claimed that the Superfund program resulted in healthier environments surrounding former waste sites. An agency study analyzed the program's health and ecological benefits and focused on former landfills, mining areas, and abandoned dumps that were cleaned up and renovated. As of January 2009, out of the approximately 500 former Superfund sites used for the study, roughly 10 percent became recreational or commercial sites. Other former Superfund sites in the study became wetlands, meadows, streams, scenic trails, parks, and habitats for plants and animals.[25]

Carbon emissions

- See also: Climate change, Greenhouse gas and Greenhouse gas emissions by state

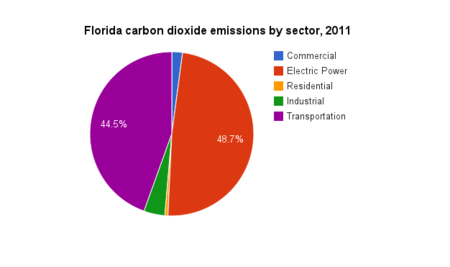

In 2011, Florida ranked fifth in carbon emissions nationwide. Florida experienced a gradual increase in CO2 emissions between 1990 and 2011. Emissions peaked in 2005 when the state emitted 260 million metric tons of greenhouse gases, but emissions declined steadily from that peak year. The vast majority of greenhouse gas emissions in Florida come from the electric power and transportation sectors, which account for 48.7 percent and 44.5 percent of all emissions, respectively. The commercial, residential and industrial sectors accounted for the remainder.[26]

Carbon dioxide emissions in Florida (in million metric tons). Data was compiled by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. |

Pollution from energy use

Pollution from energy use includes three common air pollutants: carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and ozone. These and other pollutants are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) through the National Ambient Air Quality Standards, which are federal standards limiting pollutants that can harm human health in significant concentrations. Carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, is also regulated by the EPA, but it is excluded here since it is not one of the pollutants originally regulated under the Clean Air Act for its harm to human health.

Industries and motor vehicles emit carbon monoxide directly when they use energy. Nitrogen dioxide forms from the emissions of automobiles, power plants and other sources. Ground level ozone (also known as tropospheric ozone) is not emitted but is the product of chemical reactions between nitrogen dioxide and volatile organic chemicals. The EPA tracks these and other pollutants from monitoring sites across the United States. The data below shows nationwide and regional trends for carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and ozone between 2000 and 2014. States with consistent climates and weather patterns were grouped together by the EPA to make up each region.[27][28]

Carbon monoxide (CO)

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colorless, odorless gas produced from combustion processes, e.g., when gasoline reacts rapidly with oxygen and releases exhaust; the majority of national CO emissions come from mobile sources like automobiles. CO can reduce the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and at very high levels can cause death. CO concentrations are measured in parts per million (ppm). Since 1994, federal law prohibits CO concentrations from exceeding 9 ppm during an eight-hour period more than once per year.[29][30]

The chart below compares the annual average concentration of carbon monoxide in the Northeastern and Southeastern regions of the United States between 2000 and 2014. States with consistent climates and weather patterns are grouped together by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which collects these data, to make up each region. Each line represents the annual average of all the data collected from pollution monitoring sites in each region. In the Northeast, there were 32 monitoring sites throughout 11 states, compared to 22 monitoring sites throughout six states in the Southeast. In 2000, the average concentration of carbon monoxide was 2.7 ppm in the Northeast, compared to 3.91 ppm in the Southeast. In 2014, the average concentration of carbon monoxide was 1.2 ppm in the Northeast, a decrease of 61.1 percent from 2000, compared to 1.52 ppm in the Southeast, a decrease of 56.7 percent from 2000.[31]

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2)

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is one of a group of gasses known as nitrogen oxides (NOx). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) measures NO2 as a representative for the larger group of nitrogen oxides. NO2 forms from the emissions of cars, buses, trucks, power plants, and off-road equipment. It helps form ground-level ozone and fine particle pollution, and has been linked to respiratory problems. Since 1971, federal law prohibits NO2 concentrations from exceeding a daily one-hour average of 100 parts per billion (ppb) and an annual average of 53 parts per billion (ppb).[30][32][30]

The chart below compares the annual one-hour average concentration of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) in the Northeastern and Southeastern regions of the United States between 2000 and 2014. In the Northeast, there were 32 monitoring sites throughout 11 states, compared to 14 monitoring sites throughout six states in the Southeast. In 2000, the one-hour daily average concentration of NO2 was 61.31 ppb in the Northeast, compared to 57 ppb in the Southeast. In 2014, the one-hour daily average concentration of NO2 was 43.98 ppb in the Northeast, a decrease of 28.2 percent since 2000, compared to 38.36 ppb in the Southeast, a decrease of 32.6 percent since 2000.[33]

Ground-level ozone

Ground-level ozone is created by chemical reactions between nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in sunlight. Major sources of NOx and VOCs include industrial facilities, electric utilities, automobiles, gasoline vapors, and chemical solvents. Ground-level ozone can produce health problems for children, the elderly, and asthmatics. Since 2008, federal law has prohibited ozone concentrations from exceeding a daily eight-hour average of 75 parts per billion (ppb). Beginning in 2025, federal law will prohibit ground-level ozone concentrations from exceeding a daily eight-hour average of 70 ppb.[30][34]

The chart below compares the daily eight-hour average concentration of ground-level ozone in the Northeastern and Southeastern regions of the United States between 2000 and 2014. In the chart below, ozone concentrations are measured in parts per million (ppm), which can be converted to parts per billion (ppb). In the Northeast, there were 133 monitoring sites throughout 11 states, compared to 153 monitoring sites throughout six states in the Southeast. In 2000, the daily eight-hour average concentration of ozone was 0.083 ppm, or 83 ppb in the Northeast, compared to 0.082 ppm, or 82 ppb in the Southeast. In 2014, the daily eight-hour average concentration of ozone was 0.066 ppm, or 66 ppb in the Northeast, a decrease of 19.5 percent since 2000, compared to 0.063 ppm, or 63 ppb in the Southeast, a decrease of 23.9 percent since 2000.[35]

Environmental policy in the 50 states

Click on a state below to read more about that state's energy policy.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Laws & Regulations," accessed November 25, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Understanding the Clean Air Act," accessed September 12, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Clean Water Act (CWA) Overview," accessed September 19, 2014

- ↑ The New York Times, "Clean Water Act Violations: The Enforcement Record," September 13, 2009

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Improving ESA Implementation," accessed May 15, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "ESA Overview," accessed October 1, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Endangered and threatened species in Florida," accessed July 6, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Endangered and threatened species in Florida," accessed July 6, 2015

- ↑ Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, "Florida's Endangered and Threatened Species," accessed July 21, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Annual EPA Enforcement Results Highlight Focus on Major Environmental Violations," February 7, 2014

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency, "Accomplishments by EPA Region (2013)," May 12, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Enforcement Annual Results for Fiscal Year 2012," accessed October 1, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "EPA Enforcement in 2012 Protects Communities From Harmful Pollution," December 17, 2012

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Basic Information on Mercury and Air Toxics Standards," accessed January 5, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Cleaner Power Plants," accessed January 5, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Mercury and Air Toxics Standards in Florida," accessed September 9, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Benefits and Costs of Cleaning Up Toxic Air Pollution from Power Plants," accessed October 9, 2014

- ↑ NERA Economic Consulting, "An Economic Impact Analysis of EPA's Mercury and Air Toxics Standards Rule," March 1, 2012

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "What is Superfund?" accessed September 9, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "National Priorities List (NPL) of Superfund Sites," accessed October 7, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Government Accountability Office, "EPA's Estimated Costs to Remediate Existing Sites Exceed Current Funding Levels, and More Sites Are Expected to Be Added to the National Priorities List," accessed October 7, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Estimate of National Economic Impacts of Superfund Sites," accessed September 12, 2014

- ↑ Property and Environment Research Center, "Superfund Follies, Part II," accessed October 7, 2014

- ↑ Property and Environment Research Center, "Superfund: The Shortcut That Failed (1996)," accessed October 7, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Beneficial Effects of the Superfund Program," accessed September 12, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Energy Information Administration, "State Profiles and Energy Estimates," accessed October 13, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Air Trends," accessed October 30, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Basic Information - Ozone," accessed January 1, 2016

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Carbon Monoxide," accessed October 26, 2015

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS)," accessed October 26, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Regional Trends in CO Levels," accessed October 23, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Nitrogen dioxide," accessed October 26, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Regional Trends in Nitrogen Dioxide Levels," accessed October 23, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Ground Level Ozone," accessed October 26, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Regional Trends in Ozone Levels ," accessed October 26, 2015