Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission

redistricting procedures |

|---|

2020 |

Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission is a case decided by the United States Supreme Court on April 20, 2016. At issue was the constitutionality of state legislative districts that were created by the commission in 2012. The plaintiffs, a group of Republican voters, alleged that "the commission diluted or inflated the votes of almost two million Arizona citizens when the commission intentionally and systematically overpopulated 16 Republican districts while under-populating 11 Democrat districts." This, the plaintiffs argued, constituted a partisan gerrymander. The plaintiffs claimed that the commission placed a disproportionately large number of non-minority voters in districts dominated by Republicans; meanwhile, the commission allegedly placed many minority voters in smaller districts that tend to vote Democratic. As a result, the plaintiffs argued, more voters overall were placed in districts favoring Republicans than in those favoring Democrats, thereby diluting the votes of citizens in the Republican-dominated districts. The defendants countered that the population deviations resulted from legally defensible efforts to comply with the Voting Rights Act and obtain approval from the United States Department of Justice. At the time of redistricting, certain states were required to obtain preclearance from the justice department before adopting redistricting plans or making other changes to their election laws—a requirement struck down by the United States Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder (2013).[1][2]

- See also: SCOTUS to hear major redistricting cases

- Transcript of oral argument: SupremeCourt.gov, Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission

- Transcript of decision: Supreme Court of the United States, "Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission," April 20, 2016

Background

Proposition 106

On November 7, 2000, voters in Arizona approved Proposition 106, also known as the Constitutional Amendment Relating to Creation of a Redistricting Commission. The official ballot title read as follows:

| “ | Proposing an amendment to the Constitution of Arizona; Amending Article IV, Part 2, Section 1, Constitution of Arizona; relating to ending the practice of gerrymandering and improving voter and candidate participation in elections by creating an independent commission of balanced appointments to oversee the mapping of fair and competitive congressional and legislative districts.[5][6] | ” |

Supporters of Proposition 106 included the League of Women Voters, the Arizona School Boards Association and Janet Napolitano (D), then the attorney general of Arizona. The measure was sponsored by the group Fair Districts, Fair Elections. That organization's chair, Jim Pederson, said, "When legislators draw their own lines the result is predictable. Self-interest is served first and the public interest comes in a distant second. Incumbent legislators protect their seats for today and carve out new congressional opportunities for their political future. ... Allowing legislators draw the lines is the ultimate conflict of interest."[5]

Opponents of Proposition 106 included the Arizona Chamber of Commerce, then-Representative Jim Kolbe (R) and Barry M. Aarons, a senior fellow with Americans for Tax Reform. Aarons said, "The redistricting commission amendment is a flawed proposition which will reduce the input of the will of the people of Arizona and vest disproportionate influence in the hands of bureaucratic Washington D.C. lawyers of the federal Justice Department."[5]

Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission

The Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission is responsible for drawing both congressional and state legislative district lines. The commission is composed of five members. Of these, four are selected by the majority and minority leaders of each chamber of the state legislature from a list of 25 candidates nominated by the state commission on appellate court appointments. These 25 nominees comprise 10 Democrats, 10 Republicans and five unaffiliated individuals. The four commission members appointed by legislative leaders then select the fifth member to round out the commission. The fifth member of the commission must belong to a different political party than the other commissioners. The governor, with a two-thirds vote in the Arizona State Senate, may remove a commissioner "for substantial neglect of duty, gross misconduct in office, or inability to discharge the duties of office." The Arizona State Legislature may make recommendations to the commission, but ultimate authority is vested with the commission.[7][8][9]

Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission

- See also: Judicial interpretation

Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission is a case decided by the United States Supreme Court in 2015. At issue was the constitutionality of the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission. According to Article 1, Section 4, of the United States Constitution, "the Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof." The state legislature argued that the use of the word "legislature" in this context is literal; therefore, only a state legislature may draw congressional district lines. Meanwhile, the commission contended that the word "legislature" ought to be interpreted more broadly to mean "the legislative powers of the state," including voter initiatives and referenda.[10][11]

On June 29, 2015, the United States Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in favor of the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission. The court ruled that "redistricting is a legislative function, to be performed in accordance with the state's prescriptions for lawmaking, which may include the referendum and the governor's veto." Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote the following in the court's majority opinion:[3][12]

| “ | The people of Arizona turned to the initiative to curb the practice of gerrymandering and, thereby, to ensure that Members of Congress would have “an habitual recollection of their dependence on the people.” In so acting, Arizona voters sought to restore “the core principle of republican government,” namely, “that the voters should choose their representatives, not the other way around.” The Elections Clause does not hinder that endeavor.[6] | ” |

| —Ruth Bader Ginsburg | ||

Decision

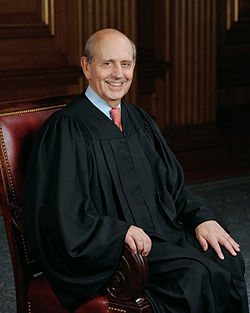

On April 20, 2016, the court ruled unanimously that the plaintiffs had failed to prove that a partisan gerrymander had taken place. Instead, the court found that the commission had acted in good faith to comply with the Voting Rights Act. Associate Justice Stephen Breyer delivered the majority opinion, which was joined by the entire court. Breyer wrote the following in the majority opinion:[3]

| “ | Appellants’ basic claim is that deviations in their apportionment plan from absolute equality of population reflect the Commission’s political efforts to help the Democratic Party. We believe that appellants failed to prove this claim because, as the district court concluded, the deviations predominantly reflected Commission efforts to achieve compliance with the federal Voting Rights Act, not to secure political advantage for one party. Appellants failed to show to the contrary.[6] | ” |

| —Stephen Breyer | ||

Election law scholar Rick Hasen wrote the following commentary about the court's ruling for Election Law Blog:[13]

| “ | [The] opinion in Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission is significant in a few ways: First, it mostly restores the 10 percent safe harbor, which gives those drawing districts greater flexibility in drawing district lines (and, though the Court doesn’t say it, more opportunity to play partisan games with under- and over-population). Only in unusual, egregious cases will this amount of deviation give rise to a successful constitutional lawsuit. Second, the Court almost holds that compliance with the Voting Rights Act’s section provides a good reason to deviate from perfect equality. Third, by writing a minimal opinion that decided only what was necessary, the Court was able to avoid a 4-4 split even though there are some great disagreements on larger issues among the Justices.[6] | ” |

Case history

- April 27, 2012: Wesley W. Harris and other voters filed suit against the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, arguing that the "final legislative map violated both the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the equal population requirement of the Arizona Constitution."[14]

- March 25, 2013: A three-judge panel of the United States District Court for the District of Arizona convened a five-day bench trial to hear the case.[14]

- April 29, 2014: The court ruled in favor of the commission, finding that "the population deviations [present in the state legislative district maps] were primarily a result of good-faith efforts to comply with the Voting Rights Act, and that even though partisanship played some role in the design of the map, the Fourteenth Amendment challenge fails." Judges Richard Clifton and Roslyn Silver sided with the commission; Judge Neil Wake dissented.[14]

- August 25, 2014: The plaintiffs appealed the district court's decision to the United States Supreme Court.[4]

- June 30, 2015: The United States Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.[4]

- December 8, 2015: Oral arguments took place.[4]

- April 20, 2016: The United States Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the state legislative district map was indeed constitutional, rejecting the arguments made by the plaintiffs.

Recent news

The link below is to the most recent stories in a Google news search for the terms Harris Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission. These results are automatically generated from Google. Ballotpedia does not curate or endorse these articles.

See also

- Arizona Creation of a Redistricting Commission, Proposition 106 (2000)

- Arizona 2000 ballot measures

- 2000 ballot measures

External links

Additional reading

Footnotes

- ↑ SCOTUSblog, "The new look at 'one person, one vote,' made simple," July 27, 2015

- ↑ Supreme Court of the United States, "Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission: Brief for Appellants," accessed April 18, 2024

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Supreme Court of the United States, "Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission," April 20, 2016 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "opinion" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "opinion" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 SCOTUSblog, "Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission," accessed December 14, 2015

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Arizona Secretary of State, "2000 Ballot Propositions and Judicial Performance Review - Proposition 106," accessed March 6, 2015

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ Supreme Court of the United States, "Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, et al. - Appellant's Jurisdictional Statement," accessed March 6, 2015

- ↑ Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, "Home page," accessed March 6, 2015

- ↑ All About Redistricting, "Arizona," accessed April 17, 2015

- ↑ The New York Times, "Court Skeptical of Arizona Plan for Less-Partisan Congressional Redistricting," March 2, 2015

- ↑ The Atlantic, "Will the Supreme Court Let Arizona Fight Gerrymandering?" September 15, 2014

- ↑ The New York Times, "Supreme Court Upholds Creation of Arizona Redistricting Commission," June 29, 2015

- ↑ Election Law Blog, "Breaking: #SCOTUS Unanimously Rejects AZ Redistricting Challenge: Analysis," April 20, 2016

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Supreme Court of the United States, "Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission: Jurisdictional Statement," August 25, 2014

|

State of Arizona Phoenix (capital) |

|---|---|

| Elections |

What's on my ballot? | Elections in 2026 | How to vote | How to run for office | Ballot measures |

| Government |

Who represents me? | U.S. President | U.S. Congress | Federal courts | State executives | State legislature | State and local courts | Counties | Cities | School districts | Public policy |