Exit polling

|

|

| Select a state from the menu below to learn more about its election administration. |

Exit polls are surveys of voters taken after they have cast their ballots. Designed to measure voters' actual choices as reported to pollsters, exit polls are different from traditional opinion polls, which take place before an election and measure voters' intended choices as reported to pollsters. Exit polls are used to project an election's outcome before all votes are tallied. Media outlets rely on exit polling to make projections about election outcomes in the immediate aftermath of an election, as it can take hours or days to tally all votes. In addition, exit polls collect demographic data about voters, as well as information about what issues motivated voters to make their choices. Political parties and candidates can use this information to strategize for future elections.

Background

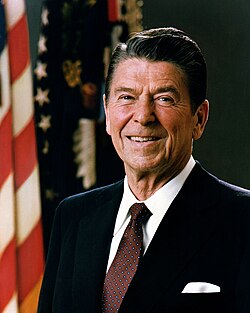

Exit polling was first employed in the United States in the 1960s. According to Time, "[N]ews organizations (and on a small scale, candidates) sought to gather demographic data about voters that could be used to predict election results." The use of exit polling expanded throughout the 1970s. During the 1980 presidential contest, NBC used exit polling data to project Ronald Reagan's victory over Jimmy Carter three hours before all polls had closed (polls on the West Coast were still open at the time NBC announced its projection). Controversy ensued as some argued that NBC's projection hampered voter turnout in those states where polls were still open. Congress held hearings on the matter, and news networks agreed to refrain from projecting states' winners until polls had closed in that state.[1][2]

In the 1990s, news networks partnered with the Associated Press to form Voter News Service, a polling consortium. Although the networks and the Associated Press continued to make their own projections, they used the same exit polling data to inform those projections, thereby "eliminating the redundancy of reports from multiple sources." In 2000, the Voter News Service incorrectly projected Al Gore (D) as the winner of the presidential contest. Later that night, the group projected George W. Bush as the winner. Later still, the consortium announced that the race was too close to call. In 2002, the Voter News Service closed.[1]

In 2003, another polling consortium was formed: the National Election Pool (NEP), which until 2017 comprised ABC, CBS, CNN, Fox News, NBC, and the Associated Press. Fox News and the Associated Press left the NEP in 2017.[3][4] Edison Research, a market research and polling firm, conducts all exit polling on behalf of the National Election Pool.[5][6][7]

Methodology

According to Joe Lenski, executive vice president of Edison Research, "The six news organizations [that make up the National Election Pool] control the editorial and financial decisions, in terms of how to allocate resources and what questions to ask." Edison Research then determines which precincts to poll and hires and trains individuals to conduct the exit polls. Interviewers ask voters to complete anonymous paper questionnaires as they leave their polling places. An interviewer records the approximate age, race, and gender of every voters who agrees to complete a questionnaire. This information is used to correlate results by demographic criteria. According to Lenski, approximately 40 to 50 percent of all voters who are asked to complete a questionnaire do so. At three points during the day, interviewers call in and report the results via telephone; the individuals taking down the results from interviewers then process the information.[5]

Prior to 5 p.m. on the day of an election, representatives from NEP news organizations are gathered in a "quarantine room" where they can view exit poll data in real time. Individuals in the quarantine room must relinquish their cell phones upon entering, and they cannot access the internet from the room. After 5 p.m., these individuals are released, and they return to their news organizations, where they can discuss the data with other reporters.[5]

| “ | To that point, they're usually only seeing the first two-thirds of the data -- the morning interviews and the afternoon interviews. We know there are different voting patterns by time of day. What they're looking for at that point is a general idea of what the story is going to be that evening, what to prepare for and some of the demographic or issue trends. You'll see reported between 5 o'clock and poll closing what issues were most important that day, or candidate quality. The types of questions that wouldn't necessarily characterize the outcome of the race.[8] | ” |

| —Joe Lenski | ||

Once polls close, Edison Research collects actual results from a series of sample precincts, which include both precincts that were exit polled and precincts that were not. Researchers then compare the sample precinct results with exit poll data and adjust the exit poll estimates as needed. Results and estimate adjustments are reported to news organizations in real time.[5]

| “ | [In] New York [in the 2016 Democratic presidential primary], we were showing a four-point margin in the exit poll at 9 o'clock, but by 9:45 we were showing a 12-point margin. That's because we can quickly compare precinct-by-precinct what the exit poll results were and what the full results for that precinct were. So we're seeing precinct-by-precinct that the actual results were that Hillary Clinton was doing four points better than she did in the exit poll in that precinct, we will adjust the results [of the exit poll] accordingly.[8] | ” |

| —Joe Lenski | ||

Projections of election outcomes are not made by pollsters, but by "decision desks" at news organizations. Decision desks comprise journalists and polling experts who make projections based both on exit polling data and actual vote returns.[1]

Criticism

Some observers question the accuracy and usefulness of exit polling data. In a 2008 article for FiveThirtyEight, statistician Nate Silver argued that exit polls have larger margins of error than traditional opinion polls. In addition, Silver cautioned that exit polls tend to overemphasize the Democratic Party's share of the vote:[9]

| “ | Although the exit polls have theoretically established procedures to collect a random sample — essentially, having the interviewer approach every nth person who leaves the polling place — in practice this is hard to execute at a busy polling place, particularly when the pollster may be standing many yards away from the polling place itself because of electioneering laws. ... Scott Rasmussen has found that Democrats supporters [sic] are more likely to agree to participate in exit polls, probably because they are more enthusiastic about this election.[8] | ” |

| —Nate Silver | ||

Nate Cohn, writing for The New York Times in 2014, argued that exit polls, while useful, should be interpreted with caution.[10]

| “ | The biggest thing to remember is that they’re just polls! They’re usually based on a sample of a few dozen precincts or so in a state, sometimes not even including many more than 1,000 respondents. Like every other type of survey, they’re subject to a margin of error because of sampling and additional error resulting from various forms of response bias.[8] | ” |

| —Nate Cohn | ||

See also

- Election policy

- Elections on Ballotpedia

- Voting policies in the United States

- Glossary of election policy terms

External links

Additional reading

- The Nation, "Reminder: Exit-Poll Conspiracy Theories Are Totally Baseless," June 7, 2016

- The Washington Post, "How exit polls work, explained," April 22, 2016

- The New York Times, "Exit Polls: Why They So Often Mislead," November 4, 2014

- FiveThirtyEight, "Ten Reasons Why You Should Ignore Exit Polls," November 4, 2008

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Time, "A Brief History of Exit Polling," November 4, 2008

- ↑ Forbes, "Are Exit Polls Reliable?" November 3, 2008

- ↑ Washington Post, "Fox News is trying to reinvent the exit poll. The survey strategy involves people who don’t vote," November 2, 2017

- ↑ Politico, "Is this the beginning of the end of the exit poll?" December 9, 2017

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 The Washington Post, "How exit polls work, explained," April 22, 2016

- ↑ Edison Research, "About us," accessed October 4, 2016

- ↑ Edison Research, "Election polling services," accessed October 4, 2016

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ FiveThirtyEight, "Ten Reasons Why You Should Ignore Exit Polls," November 4, 2008

- ↑ The New York Times, "Exit Polls: Why They So Often Mislead," November 4, 2014