Court cases related to federalism

| Federalism |

|---|

| •Key terms • Court cases •Major arguments • State responses to federal mandates •State oversight of federal grants • Federalism by the numbers • Index |

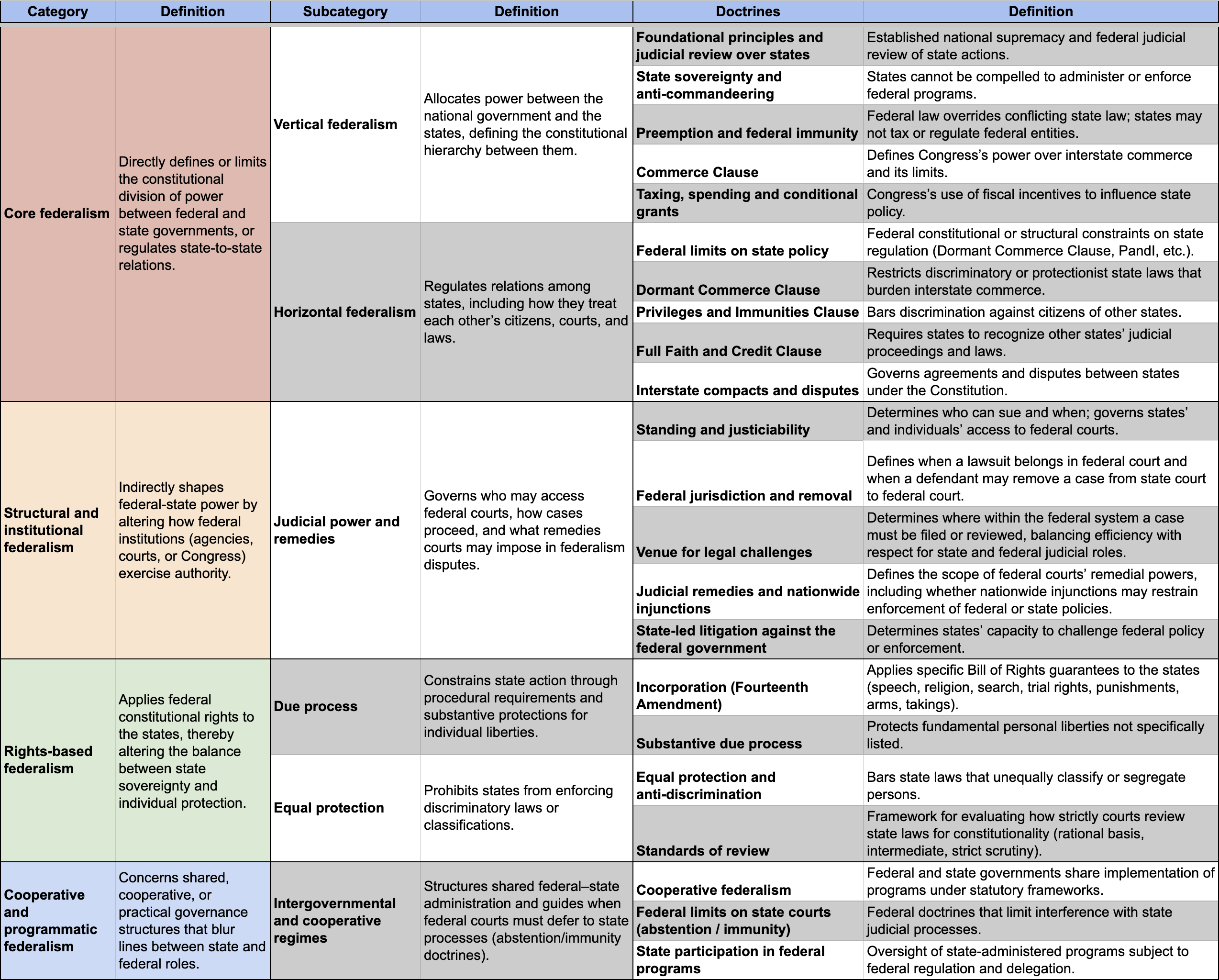

Federalism in the United States is the constitutional system that divides authority between the national and state governments. Over time, the U.S. Supreme Court has defined and refined that division through judicial doctrines — legal principles that determine when national power prevails and when states retain autonomy.

This page organizes the major doctrines and the landmark cases that established them into four broad categories: core, structural and institutional, rights-based, and cooperative. Together, these cases demonstrate how the Constitution and the courts have shaped the balance of power between the states and the federal government.

- Core federalism – Defines the constitutional division of power between the national government and the states, including vertical doctrines like federal supremacy and state sovereignty, and horizontal doctrines governing relations among states.

- Structural and institutional federalism – Explains how the structure and operation of federal institutions shape federal–state power through doctrines governing judicial access, venue, standing, and remedies.

- Rights-based federalism – Applies federal constitutional rights to the states through due process and equal protection, limiting state authority in areas such as individual liberty, criminal procedure, and equality.

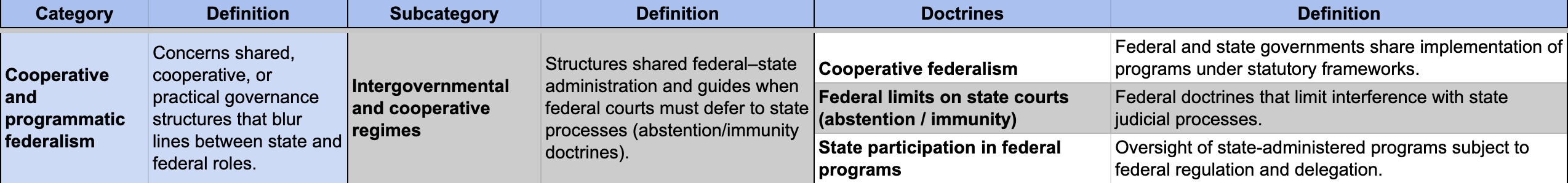

- Cooperative and programmatic federalism – Addresses shared governance systems where state and federal governments jointly administer programs, emphasizing coordination, abstention doctrines, and limits on federal coercion of state participation.

The following taxonomy presents each category, subcategory, and doctrine with definitions of each. It serves as a clear reference for understanding how different strands of federalism interact and how courts apply them in practice. Each category identifies a broad area of federal–state authority, each subcategory narrows the focus to a specific dimension of that authority, and each doctrine shows the precise legal rule courts use to resolve federalism disputes.

- Defines federal–state authority

- Federal rights applied to the states

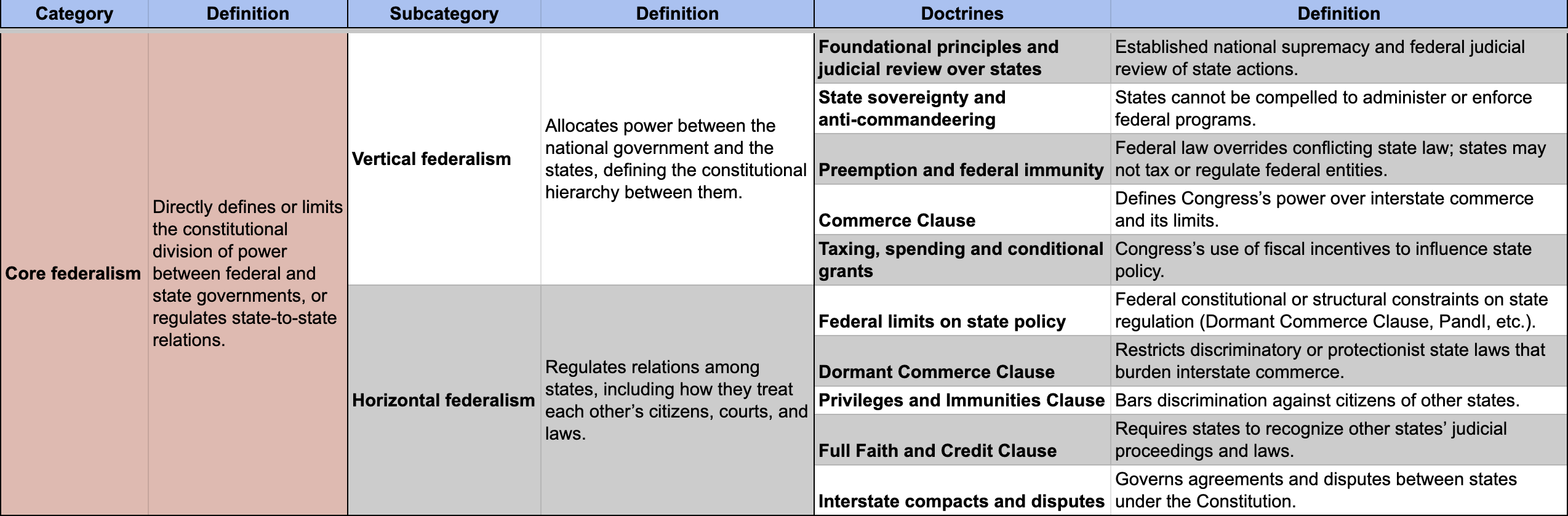

Core federalism

These doctrines directly define the constitutional balance between the national government and the states, and how states relate to one another. They set the baseline rules for supremacy, state sovereignty, and the fiscal and commercial constraints that shape state policy space.

Vertical federalism

This branch addresses the allocation of authority between the national government and the states. It includes national supremacy, limits on commandeering states, and when federal law displaces state law.

Foundational principles and judicial review over states

These decisions established federal supremacy and federal judicial review of state actions. They explain when state authority yields to national powers and federal courts.

- Martin v. Hunter's Lessee (1816) – federal appellate review of state judgments on federal questions.

- McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) – implied federal powers; states cannot tax federal instruments.

- Ableman v. Booth (1859) – state courts may not obstruct federal judgments or officers; confirms federal judicial supremacy over conflicting state process.

- Texas v. White (1869) – the Union is “indestructible,” defining states’ legal status post-war.

- Hans v. Louisiana (1890) – state sovereign immunity bars suits by a state’s own citizens.

State sovereignty and anti-commandeering

These cases prevent Congress from directing state legislatures or conscripting state officers to administer federal programs. They preserve state political accountability for state lawmaking.

- New York v. United States (1992) – Congress cannot compel state legislation (“take-title”).

- Printz v. United States (1997) – no federal commands to state executive officers.

- Bond v. United States (2011) – individuals can invoke federalism limits protecting state spheres.

- Murphy v. NCAA (2018) – Congress may not forbid states from changing their own laws.

Preemption and federal immunity

These doctrines determine when federal statutes, regulations, or treaties displace state law under the Supremacy Clause, and where states retain room to regulate.

- Ware v. Hylton (1796) – treaties prevail over contrary state statutes.

- Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842) – early preemption holding limiting state interference with a federal enforcement scheme; foreshadows anti-commandeering by allowing states to decline to administer federal policy.

- Collector v. Day (1871) – intergovernmental tax-immunity (as then understood) barred federal taxation of core state officers; overruled by Graves v. New York ex rel. O'Keefe (1939).

- Missouri v. Holland (1920) – treaty implementation can override conflicting state rules.

- Arizona v. United States (2012) – state immigration provisions preempted.

Commerce Clause

These rulings define the reach of federal regulation over interstate markets and when local activity remains for states to govern.

- Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) – navigation within “commerce” and supremacy over state monopoly.

- Swift & Co. v. United States (1905) – “stream of commerce” supports national regulation.

- Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918) – child-labor shipment ban invalid (later overruled).

- A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (1935) – New Deal code invalid as applied to intrastate activity.

- United States v. Darby Lumber Co. (1941) – broad federal power over goods in commerce.

- Wickard v. Filburn (1942) – local production may be regulated when aggregated effects are substantial.

- United States v. Lopez (1995) – limit on federal reach to non-economic local conduct.

- United States v. Morrison (2000) – federal civil remedy invalid where conduct is non-economic.

- Gonzales v. Raich (2005) – aggregation supports national control of integrated markets.

Taxing, spending and conditional grants

These cases govern Congress’s use of the purse to influence state policy and participation in national programs, distinguishing inducement from coercion.

- Hylton v. United States (1796) – carriage tax treated as an excise, not a direct tax.

- Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. (1895) – direct tax/apportionment (pre-16th Amendment).

- Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co. (1922) – penalty disguised as tax struck down.

- United States v. Butler (1936) – invalid use of tax power to control local production.

- Steward Machine Co. v. Collector of Internal Revenue (1937) – cooperative tax/credit design sustained.

- Helvering v. Davis (1937) – Social Security spending power sustained.

- South Dakota v. Dole (1987) – conditional grants upheld within limits.

- National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) v. Sebelius (2012) – coercive Medicaid conditions invalid.

Horizontal federalism

These doctrines regulate how states treat each other’s citizens, courts, and markets. They limit protectionism, require respect for judgments, and structure interstate agreements.

Federal limits on state policy

These principles cabin state regulation when it burdens interstate trade or other states’ residents, preserving a national market while allowing legitimate local aims.

- Munn v. Illinois (1877) – upholds state rate regulation of a business “affected with a public interest,” marking a federal constitutional space for state economic regulation consistent with national structure.

- Chicago v. Atchison, T. & S. F. R. Co. (1958) – local terminal rules constrained when they burden interstate rail.

- Granholm v. Heald (2005) – anti-protectionism applied to direct shipment of wine.

Dormant Commerce Clause

These cases bar discriminatory or unduly burdensome state laws that fragment the national market.

- Cooley v. Board of Wardens (1852) – established “selective exclusiveness”: states may regulate local aspects of commerce absent a need for national uniformity or conflicting federal law.

- South Dakota v. Wayfair (2018) – modernized nexus rules; undue-burden limits remain.

- National Pork Producers Council v. Ross (2023) – facial challenge failed; extraterritorial effects alone are not dispositive.

Privileges and Immunities Clause

These rulings prevent a state from disadvantaging citizens of other states in fundamental pursuits.

- Saenz v. Roe (1999) – reinforced right to travel and equal treatment of new residents.

Full Faith and Credit Clause

These doctrines require states to respect sister-state judgments and, within limits, laws.

- Franchise Tax Board v. Hyatt (2019) – reaffirmed sovereign-immunity comity across state lines.

Interstate compacts and disputes

These rules govern state-to-state boundary settlements and cooperative compacts.

- Virginia v. Tennessee (1893) – not all compacts need express congressional consent.

- New Jersey v. Delaware (2008) – allocation of boundary/river authority clarified.

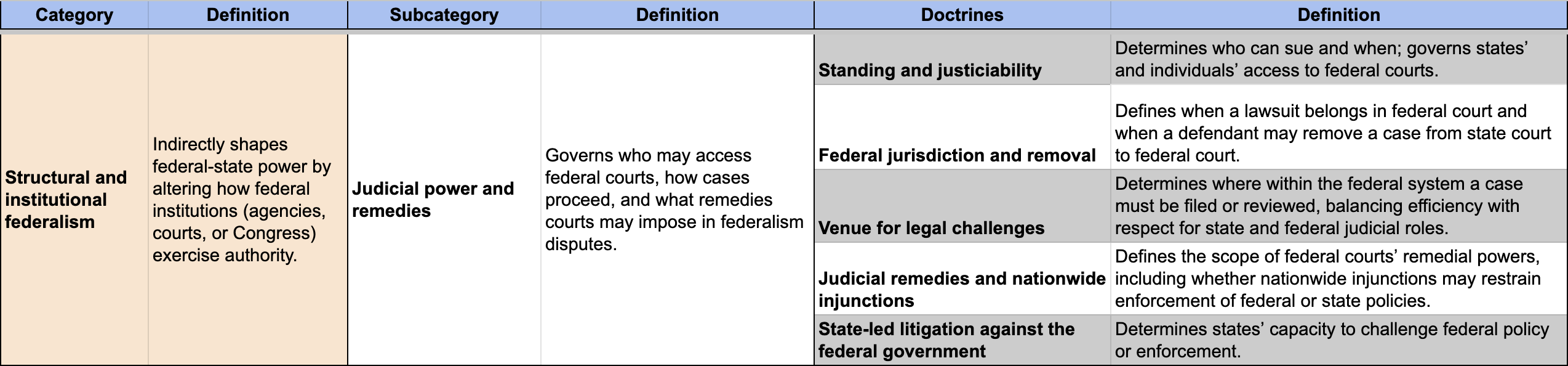

Structural and institutional federalism

These doctrines shape federal–state power indirectly by defining how federal institutions—especially the courts—exercise authority that affects state interests. They focus on judicial access, procedural limits, and the remedies available when states challenge or defend against federal action.

Judicial power and remedies

These doctrines determine who can sue, where, and what remedies federal courts can impose. They influence when states can press or resist federal policy in court.

Standing and justiciability

These thresholds govern who may invoke federal courts and on what record; states often rely on sovereign or special-solicitude interests.

- Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency (2007) – state standing recognized to seek greenhouse-gas regulation.

- United States v. Texas (2023) – states lacked standing to contest federal enforcement priorities; the Court held they lacked Article III standing, limiting state authority to contest federal nonenforcement policies.

Federal jurisdiction and removal

These doctrines define when cases belong in federal court and when defendants can remove from state court, ensuring federal issues are heard in federal fora without displacing legitimate state adjudication.

- Franchise Tax Board v. Construction Laborers Vacation Trust (1983) – kept most state-law cases in state court unless federal issues dominate.

- Grable & Sons Metal Products v. Darue Engineering & Manufacturing (2005) – allowed federal court only when a state claim turns on an important federal question.

Venue for legal challenges

These rules identify the proper federal venue to file or review challenges, including multi-state disputes, balancing efficiency with respect for state and federal judicial roles.

- Oklahoma v. EPA (2025) – clarified venue/filing posture for region-wide environmental challenges.

Judicial remedies and nationwide injunctions

These doctrines define the scope of equitable relief, including universal injunctions, calibrating federal courts’ power to halt federal or state policies affecting multiple states.

- Ex parte Young (1908) – allowed federal courts to enjoin state officials enforcing unconstitutional laws.

- Trump v. CASA, Inc. (2025) – examined constraints on nationwide relief against federal policy.

State-led litigation against the federal government

Determines when and how states can bring lawsuits against the federal government to protect their own interests or challenge federal actions affecting their authority. For examples of modern federalism disputes—including multistate lawsuits, challenges to federal rules, and efforts to block or enforce national mandates—see the State responses to federal mandates page.

- Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency (2007) – recognized state standing to compel federal action.

- United States v. Texas (2023) – clarified limits on state standing and remedies.

- West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency (2022) – example of coordinated multistate challenge shaping national policy.

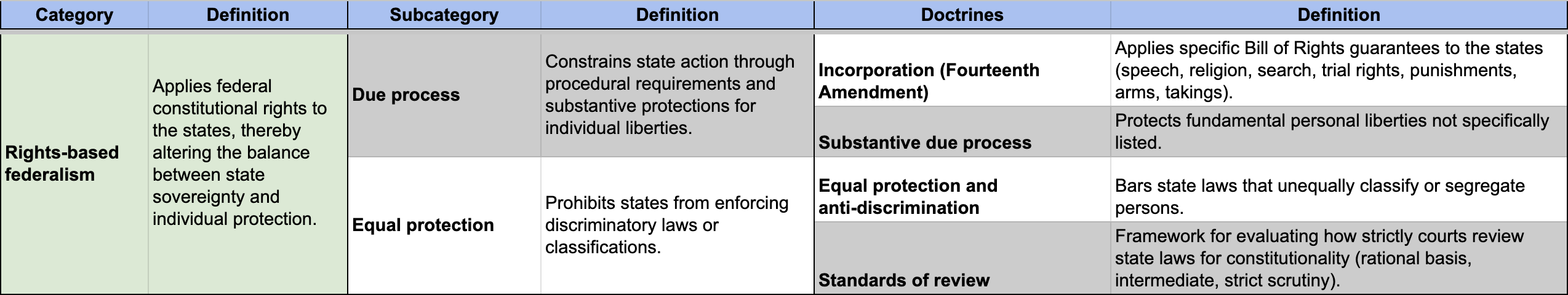

Rights-based federalism

These doctrines apply federal rights against the states and thereby limit state sovereignty. They reset state policy space where the Constitution protects individual liberty or equality.

Due process

This pillar constrains state action through procedural and substantive protections. It both incorporates enumerated rights and safeguards certain unenumerated liberties.

Incorporation (Fourteenth Amendment)

These rulings applied Bill of Rights protections—speech, religion, search, trial rights, punishments, arms, takings—to the states, restricting state and local governments in areas once left to state law.

- Barron v. Baltimore (1833) – explains why incorporation was later required: the Bill of Rights originally constrained only the federal government, leaving states free until the Fourteenth Amendment changed the baseline.

- Hurtado v. California (1884) – grand jury not required by Fourteenth Amendment.

- Gitlow v. New York (1925) – speech.

- Mapp v. Ohio (1961) – exclusionary rule.

- Engel v. Vitale (1962) – school prayer.

- Robinson v. California (1962) – Eighth Amendment/status offense.

- Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) – right to counsel.

- Malloy v. Hogan (1964) – self-incrimination.

- Aguilar v. Texas (1964) – probable-cause standards for state warrants.

- Pointer v. Texas (1965) – confrontation right.

- Parker v. Gladden (1966) – fair-trial/confrontation.

- Miranda v. Arizona (1966) – custodial warnings bind state police.

- Bradenburg v. Ohio (1969) – incitement standard for speech.

- Benton v. Maryland (1969) – double jeopardy.

- McDonald v. Chicago (2010) – Second Amendment.

- Timbs v. Indiana (2019) – Excessive Fines Clause.

Substantive due process

These decisions protect fundamental personal choices from state interference, defining when state regulation of family, intimacy, or bodily autonomy goes too far.

- Lochner v. New York (1905) – liberty of contract (now repudiated).

- Buck v. Bell (1927) – compulsory sterilization (historical/deferential).

- West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish (1937) – upholding state minimum wage; end of Lochner era.

- Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) – marital privacy.

- Michael H. v. Gerald D. (1989) – deference to state family-law framework.

- Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health (1990) – end-of-life standards in state law.

- Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) – returned abortion regulation primarily to the states, subject to other constraints.

Equal protection

This pillar bars discriminatory state classifications and segregation. It sets the review standards that police state laws drawing lines among persons.

Equal protection and anti-discrimination

These cases prohibit states from enforcing racial segregation or other invidious distinctions, and define what counts as impermissible line-drawing.

- Sweatt v. Painter (1950) – separate law school unequal.

- McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents (1950) – higher-ed segregation invalid.

- Briggs v. Elliott (1952) – companion to Brown.

- Brown v. Board of Education (1954) – dismantled de jure school segregation.

- Bolling v. Sharpe (1954) – federal D.C. schools (Fifth Amendment).

- Reynolds v. Sims (1964) – one-person, one-vote for state legislatures.

- Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1971) – remedial authority to cure state segregation.

- Romer v. Evans (1996) – statewide withdrawal of protections invalid.

- Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard (2023) – restricted race-conscious admissions; state actors must use race-neutral means.

Standards of review

These doctrines decide how strictly courts scrutinize state classifications—strict, intermediate, or rational-basis review.

- San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez (1973) – rational-basis review applied to school finance.

- Craig v. Boren (1976) – intermediate scrutiny for sex classifications.

- United States v. Skrmetti (2024) – addressed the level of scrutiny and constitutional framework for state regulations affecting minors’ medical treatments.

Cooperative and programmatic federalism

These doctrines address shared governance in which federal and state actors jointly administer programs. They emphasize partnership, preemption boundaries, and judicial respect for state processes.

Intergovernmental and cooperative regimes

This heading captures frameworks where states implement federal statutes by plan or waiver, highlighting incentives, conditions, and limits to federal leverage.

Cooperative federalism

These cases sustain federal floors while allowing states to administer programs through approved plans, preserving state choices within federal baselines.

- Hodel v. Virginia Surface Mining (1981) – minimum national standards; state plans.

- NFIB v. Sebelius (2012) – limited coercive funding conditions.

Federal limits on state courts (abstention / immunity)

These doctrines restrict federal interference with ongoing state proceedings while preserving federal rights review, respecting state courts’ primary role in enforcing state law.

- Louisiana v. Jumel (1883) – immunity limits on compelling state fiscal action.

- Hagood v. Southern (1886) – similar sovereign-immunity constraints.

- In re Ayers (1887) – sovereign-immunity bar on suits effectively against the state.

- Younger v. Harris (1971) – abstention from enjoining state prosecutions.

State participation in federal programs

These disputes involve oversight of state-implemented, federally supervised schemes, defining how far federal agencies can push states and how much discretion states retain.

- West Virginia v. EPA (2022) – limited federal authority under cooperative environmental programs.

- San Francisco v. EPA (2024) – clarified federal–local boundaries under the Clean Water Act.

See also

External links

Footnotes

| ||||||||||||||||||||