Maryland General Assembly

| Maryland General Assembly | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type: | State legislature |

| Term limits: | None |

| Session start: | January 8, 2025 |

| Website: | Official Legislature Page |

| Leadership | |

| Senate President: | William Ferguson IV (D) |

| House Speaker: | Adrienne Jones (D) |

| Majority Leader: | Senate: Nancy King (D) House: David Moon (D) |

| Minority Leader: | Senate: Stephen Hershey Jr. (R) House: Jason Buckel (R) |

| Structure | |

| Members: | 47 (Senate), 141 (House) |

| Length of term: | 4 years (Senate), 4 years (House) |

| Authority: | Art III, Maryland Constitution |

| Salary: | $46,061/year + per diem |

| Elections | |

| Last election: | November 8, 2022 |

| Next election: | November 3, 2026 |

| Redistricting: | Maryland General Assembly has control |

The Maryland General Assembly is the state legislature of Maryland. It is a bicameral body. The upper house, the Maryland State Senate, has 47 members and the lower house, the Maryland House of Delegates, has 141 members. Each member represented an average of 37,564 residents, as of the 2000 Census.[1] The General Assembly meets each year for 90 days to act on more than 2,300 bills including the State's annual budget, which it must pass before adjourning. Like the Governor of Maryland, members of both houses serve four-year terms. Each house elects its own officers, judges the qualifications and election of its own members, establishes rules for the conduct of its business, and may punish or expel its own members.

The Maryland General Assembly convenes within the State House in Annapolis.

Maryland has a divided government, and no political party holds a state government trifecta. A trifecta exists when one political party simultaneously holds the governor’s office and majorities in both state legislative chambers. As of November 13, 2025, there are 23 Republican trifectas, 14 Democratic trifectas, and 13 divided governments where neither party holds trifecta control.

In the 2020 election, Republicans had a net gain of two trifectas and two states under divided government became trifectas. Prior to that election, Maryland had a divided government. There were 21 Republican trifectas, 15 Democratic trifectas, and 14 divided governments.

Elections

2018

Elections for the Maryland State Senate took place in 2018. The closed primary election took place on June 26, 2018, and the general election was held on November 6, 2018. The candidate filing deadline was February 27, 2018. The filing deadline for third party and independent candidates was August 6, 2018.[2]

Elections for the Maryland House of Delegates took place in 2018. The closed primary election took place on June 26, 2018, and the general election was held on November 6, 2018. The candidate filing deadline was February 27, 2018. The filing deadline for third party and independent candidates was August 6, 2018[3]

Sessions

Article III of the Maryland Constitution establishes when the General Assembly is to be in session. Section 14 of Article III states that the General Assembly is to convene in regular session every year on the second Wednesday of January.

Section 14 also contains the procedures for convening extraordinary sessions of the General Assembly. If a majority of the members of each legislative house petition the Governor of Maryland with a request for an extraordinary session, the Governor is constitutionally required to proclaim an extraordinary session.

Article II of the Maryland Constitution also gives the Governor of Maryland the power to proclaim an extraordinary session without the request of the General Assembly. Sessions last for 90 continuous days but can be extended for up to 30 days by vote of the legislature.

2025

In 2025, the legislature was scheduled to convene on January 8, 2025, and adjourn on April 7, 2025.

| Click [show] for past years' session dates. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

2024In 2024, the legislature was scheduled to convene on January 10, 2024, and adjourn on April 8, 2024. 2023In 2023, the legislature was scheduled to convene on January 11, 2023, and adjourn on April 10, 2023. 2022In 2022, the legislature was scheduled to convene on January 12, 2022, and adjourn on April 11, 2022. 2021In 2021, the legislature was scheduled to convene on January 13, 2021, and adjourn on April 12, 2021. 2020In 2020, the legislature was scheduled to convene on January 8, 2020, and adjourn on March 18, 2020.

Several state legislatures had their sessions impacted as a result of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. The Maryland State Legislature adjourned its session early, effective March 18, 2020, in response to the coronavirus pandemic.[4] 2019In 2019, the legislature was in session from January 9, 2019, through April 8, 2019. 2018In 2018, the legislature was in session from January 10, 2018, through April 9, 2018. To read about notable events and legislation from this session, click here. 2017

In 2017, the legislature was in session from January 11, 2017, through April 10, 2017. 2016

In 2016, the legislature was in session from January 13 through April 11. 2015

In 2015, the legislature was in session from January 14 through April 13. Major issues in 2015Major issues in the 2015 legislative session included the state budget shortfall, expanding charter schools, marijuana decriminalization, fracking, and heroin overdoses.[5] 2014

In 2014, the legislature was in session from January 8 to April 7. Major issues in 2014Major issues during the 2014 legislative session included addressing the state's minimum wage, emergency health insurance, marijuana legalization, and tax relief.[6] 2013

In 2013, the legislature was in session from January 9 to April 8. Major issues in 2013Major issues during the 2013 legislative session included an assault weapons ban, boosting the state's wind power industry, transportation funding, and repeal of the death penalty.[7] 2012

In 2012, the legislature was in session from January 11 through April 19. 2011In 2011, the legislature was in session from January 12 through April 8.[8] A special redistricting session was held from October 17 to October 20.[9][10] 2010In 2010, the legislature was in session from January 13 to April 10.[11] |

Role in state budget

- See also: Maryland state budget and finances

| Maryland on |

The state operates on an annual budget cycle. The sequence of key events in the budget process is as follows:[12]

- Budget instructions are sent to state agencies in June of the year preceding the start of the new fiscal year.

- State agencies submit their budget requests to the governor between August and October.

- The governor submits his or her proposed budget to the state legislature on the third Wednesday in January.

- The legislature typically adopts a budget by the 83rd day of the session. A simple majority is required to pass a budget. The fiscal year begins July 1.

Maryland is one of 44 states in which the governor has line item veto authority.[12][13][14][15]

The governor is constitutionally required to submit a balanced budget proposal. Likewise, the legislature is required to adopt a balanced budget.[12]

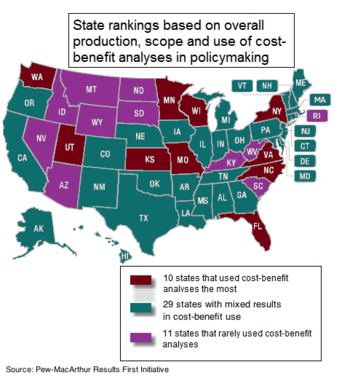

Cost-benefit analyses

The Pew-MacArthur Results First Initiative is a joint project of the Pew Charitable Trusts and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation that works to partner with states in implementing cost-benefit analysis models.[16]. The initiative released a report in July 2013 concluding that cost-benefit analysis in policymaking led to more effective uses of public funds. Looking at data from 2008 through 2011, the study's authors found that some states were more likely to use cost-benefit analysis, while others were facing challenges and lagging behind the rest of the nation. The challenges states faced included a lack of time, money, and technical skills needed to conduct comprehensive cost-benefit analyses. Maryland was one of 29 states with mixed results regarding the frequency and effectiveness of its use of cost-benefit analysis.[17]

Ethics and transparency

Following the Money report

- See also: "Following the Money" report, 2015

The U.S. Public Interest Research Group, a consumer-focused nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C., released its annual report on state transparency websites in March 2015. The report, entitled "Following the Money," measured how transparent and accountable state websites were with regard to state government spending.[18] According to the report, Maryland received a grade of B+ and a numerical score of 87, indicating that Maryland was "Advancing" in terms of transparency regarding state spending.[18]

Open States Transparency

The Sunlight Foundation released an "Open Legislative Data Report Card" in March 2013. Maryland was given a grade of B in the report. The report card evaluated how adequate, complete, and accessible legislative data was to the general public. A total of 10 states received an A: Arkansas, Connecticut, Georgia, Kansas, New Hampshire, New York, North Carolina, Texas, Virginia, and Washington.[19]

Dual employment and financial disclosure requirements

State ethics regulations regarding dual public employment and income disclosure for legislators vary across the United States. A January 2015 report by the National Council of State Legislatures (NCSL) concluded that legislators in 33 states are not permitted to maintain additional paid government employment during their terms in office.[20] The NCSL published a report in June 2014 that counted 47 states with disclosure requirements for outside income, business associations, and property holdings. The exceptions to these disclosure categories were Idaho, Michigan, and Vermont.[21] Click show on the right side of the table below to compare state policies:

| Ethics regulations for state legislators | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | Allows additional paid public employment? | Requires disclosure of financial interests? |

| Alabama | ||

| Alaska | ||

| Arizona | ||

| Arkansas | ||

| California | ||

| Colorado | ||

| Connecticut | ||

| Delaware | ||

| Florida | ||

| Georgia | ||

| Hawaii | ||

| Idaho | ||

| Illinois | ||

| Indiana | ||

| Iowa | ||

| Kansas | ||

| Kentucky | ||

| Louisiana | ||

| Maine | ||

| Maryland | ||

| Massachusetts | ||

| Michigan | ||

| Minnesota | ||

| Mississippi | ||

| Missouri | ||

| Montana | ||

| Nebraska | ||

| Nevada | ||

| New Hampshire | ||

| New Jersey | ||

| New Mexico | ||

| New York | ||

| North Carolina | ||

| North Dakota | ||

| Ohio | ||

| Oklahoma | ||

| Oregon | ||

| Pennsylvania | ||

| Rhode Island | ||

| South Carolina | ||

| South Dakota | ||

| Tennessee | ||

| Texas | ||

| Utah | ||

| Vermont | ||

| Virginia | ||

| Washington | ||

| West Virginia | ||

| Wisconsin | ||

| Wyoming | ||

Legislative districts

The current pattern for distribution of seats began with the legislative apportionment plan of 1972 and has been revised every ten years thereafter according to the results of the decennial U.S. Census. A Constitutional amendment, the plan created 47 legislative districts, many of which cross county boundaries to delineate districts relatively equal in population. Each legislative district elects one senator and three delegates. In most districts, the three delegates are elected at large from the whole district via block voting. However, in some more sparsely populated areas of the state, the districts are divided into subdistricts for the election of delegates: either into three one-delegate subdistricts or one two-delegate subdistrict and one one-delegate subdistrict.

Redistricting

- See also: Redistricting in Maryland

Maryland employs two distinct processes for state legislative and Congressional redistricting. The General Assembly bears primary responsibility, proposing and passing the redistricting plan as ordinary legislation, and the Governor of Maryland can veto the plan. For state legislative redistricting, the Governor is responsible for drafting plans and submitting the new maps to the General Assembly. The Governor, aided by an advisory commission, submits a plan, and the chamber leadership introduces the plan as a joint resolution. The General Assembly may then adopt the plan or pass another. If a plan is not adopted by the 45th day of the session, the Governor's plan becomes law.[22]

2010

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Maryland's population grew from 5.30 million to 5.77 million between 2000 and 2010.[23] The growth rate was slightly below the national average, but was one of the fastest rates in the Northeast. Maryland retained all eight Congressional districts, but population shifts suggested that many districts would need to be redrawn.[24] The City of Baltimore lost population relative to other areas of the state.[25]

Gov. Martin O'Malley introduced a state legislative plan on January 11, 2012. Members of the legislature produced alternative plans, but no hearings were scheduled. O'Malley's map became law in February 2012 without a vote.[26] The map-making process had been criticized for the inclusion of a tax evader on the Redistricting Advisory Committee, but O'Malley noted that the financial troubles of this member were not made known to him or the public until later in the process, and this individual was cut off from the process after that point.[27]

The Congressional district map was challenged by petitioners, but a drive to place the matter before voters failed after many of the signatures gathered were voided in a legal decision.[28][29]

Leadership

The Senate is led by a President and the House by a Speaker whose respective duties and prerogatives enable them to influence the legislative process significantly. The President and the Speaker appoint the members of most committees and name their chairs and vice-chairs, except in the case of the Joint Committee on Investigation whose members elect their own officers. The President and Speaker preside over the daily sessions of their respective chambers, maintaining decorum and deciding points of order. As legislation is introduced, they assign it to a standing committee for consideration and a public hearing. The president pro tempore appoints majority and minority whips and leaders.

Legislators

Salaries

- See also: Comparison of state legislative salaries

| State legislative salaries, 2024[30] | |

|---|---|

| Salary | Per diem |

| $54,437/year | $115/day for lodging. $63/day for meals. |

When sworn in

Maryland legislators assume office the second Wednesday in January after the election.

Senate

The Maryland State Senate is the upper house of the General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is composed of 47 senators elected from single-member districts. Maryland was required to use 2010 Census adjusted population numbers for redistricting, pursuant to the "No Representation Without Population Act" (SB 400/HB 496) signed into law in 2010. Generally, the law requires that the census data must be adjusted to reassign Maryland residents in state and federal correctional institutions to their last known address, and to exclude out-of-state residents in correctional institutions for the purposes of creating congressional, state legislative and local districting plans. Each member represented an average of 122,813 residents[31]. After the 2000 Census, each member represented 112,691.[32]

| Party | As of November 2025 | |

|---|---|---|

| Democratic Party | 33 | |

| Republican Party | 13 | |

| Other | 0 | |

| Vacancies | 1 | |

| Total | 47 | |

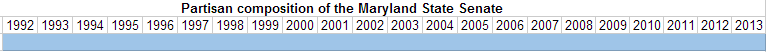

The chart below shows the partisan composition of the Maryland State Senate from 1992 to 2013.

House of Delegates

The Maryland House of Delegates is the lower house of the General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland, and is composed of 141 delegates elected from 47 districts. Maryland was required to use 2010 Census adjusted population figures for Maryland Redistricting, pursuant to the "No Representation Without Population Act" (SB 400\HB 496) signed into Maryland law in 2010. Generally, the law requires that the census data must be adjusted to reassign Maryland residents in state and federal correctional institutions to their last known address, and to exclude out-of-state residents in correctional institutions for the purposes of creating congressional, state legislative and local districting plans. Each member represented an average of 40,938 residents.[31] After the 2000 Census, each member represented 37,564 residents on average.[33]

| Party | As of November 2025 | |

|---|---|---|

| Democratic Party | 102 | |

| Republican Party | 38 | |

| Other | 0 | |

| Vacancies | 1 | |

| Total | 141 | |

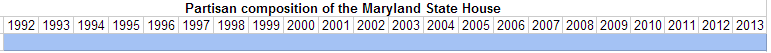

The chart below shows the partisan composition of the Maryland House of Delegates from 1992 to 2013.

Veto overrides

- See also: Veto overrides in state legislatures

State legislatures can override governors' vetoes. Depending on the state, this can be done during the regular legislative session, in a special session following the adjournment of the regular session, or during the next legislative session. The rules for legislative overrides of gubernatorial vetoes in Maryland are listed below.

How many legislators are required to vote for an override? Three-fifths of members in both chambers.

| Three-fifths of members in both chambers must vote to override a veto, which is 85 of the 141 members in the Maryland House of Delegates and 29 of the 47 members in the Maryland State Senate. Maryland is one of seven states that requires a three-fifths vote from both of its legislative chambers to override a veto. |

How can vetoes be overridden after the legislature has adjourned?

| Vetoes can be overridden in a special session or when the next regular session convenes.[34] A majority of members in both chambers must agree to call for a special session.[35] |

Authority: Article II, Section 17 of the Maryland Constitution.

| "Each House may adopt by rule a veto calendar procedure that permits Bills that are to be reconsidered to be read and voted upon as a single group. The members of each House shall be afforded reasonable notice of the Bills to be placed on each veto calendar. Upon the objection of a member, any Bill shall be removed from the veto calendar. If, after such reconsideration, three-fifths of the members elected to that House pass the Bill, it shall be sent with the objections to the other House, by which it shall likewise be reconsidered, and if it passes by three-fifths of the members elected to that House it shall become a law." |

History

Partisan balance 1992-2013

Maryland State Senate: During every year from 1992-2013, the Democratic Party was the majority in the Maryland State Senate. The Maryland State Senate is one of 16 state Senates that were Democratic for more than 80 percent of the years between 1992 and 2013. Maryland was under a Democratic trifecta for the last seven years of the study period.

Across the country, there were 541 Democratic and 517 Republican state Senates from 1992 to 2013.

Maryland House of Delegates: During every year from 1992 to 2013, the Democratic Party was the majority in the Maryland State House of Representatives. The Maryland House of Delegates is one of 18 state Houses that were Democratic for more than 80 percent of the years between 1992-2013. Maryland was under a Democratic trifecta for the last seven years of the study period.

Across the country, there were 577 Democratic and 483 Republican state Houses of Representatives from 1992 to 2013.

Over the course of the 22-year study, state governments became increasingly more partisan. At the outset of the study period (1992), 18 of the 49 states with partisan legislatures had single-party trifectas and 31 states had divided governments. In 2013, only 13 states had divided governments, while single-party trifectas held sway in 36 states, the most in the 22 years studied.

The chart below shows the partisan composition of the Office of the Governor of Maryland, the Maryland State Senate and the Maryland House of Delegates from 1992 to 2013.

SQLI and partisanship

- To read the full report on the State Quality of Life Index (SQLI) in PDF form, click here.

The chart below depicts the partisanship of the Maryland state government and the state's SQLI ranking for the years studied. For the SQLI, the states were ranked from 1-50, with 1 being the best and 50 the worst. Maryland experienced two long periods of Democratic trifectas, between 1992 and 2002 and again between 2007 and 2013. The state cracked the top-10 in the SQLI ranking in three separate years (2002, 2006, and 2008), twice under a Democratic trifecta and once under divided government. Maryland ranked lowest on the SQLI ranking in two separate years (1992 and 1995), in which the state placed 25th under a Democratic trifecta. Maryland has never had a Republican trifecta.

- SQLI average with Democratic trifecta: 16.35

- SQLI average with Republican trifecta: N/A

- SQLI average with divided government: 10.75

Joint committees

- See also: Public policy in Maryland

The Maryland General Assembly has eighteen (18) standing committees.

- Administrative, Executive and Legislative Review

- Audit

- Chesapeake and Atlantic Coastal Bays Critical Area

- Children, Youth, and Families

- Cybersecurity, Information Technology and Biotechnology

- Fair Practices and State Personnel Oversight

- Federal Relations

- Gaming Oversight

- Investigation

- Legislative Ethics

- Legislative Information Technology and Open Government

- Legislative Policy

- Management of Public Funds

- Port of Baltimore

- Protocol

- Spending Affordability

- Unemployment Insurance Oversight

- Workers' Compensation Benefit and Insurance

Constitutional amendments

In every state but Delaware, voter approval is required to enact a constitutional amendment. In each state, the legislature has a process for referring constitutional amendments before voters. In 18 states, initiated constitutional amendments can be put on the ballot through a signature petition drive. There are also many other types of statewide measures.

The methods by which the Maryland Constitution can be amended:

Article XIV of the Maryland Constitution defines two ways to amend the state constitution—through a legislative process and a state constitutional convention.

Legislature

A 60% vote is required during one legislative session for the Maryland State Legislature to place a constitutional amendment on the ballot. That amounts to a minimum of 85 votes in the Maryland House of Delegates and 29 votes in the Maryland State Senate, assuming no vacancies. Amendments do not require the governor's signature to be referred to the ballot.

Convention

According to Section 2 of Article XIV of the Maryland Constitution, a question about whether to hold a state constitutional convention is to automatically appear on the state's ballot every 20 years starting in 1970. Maryland is one of 14 states that provides for an automatic constitutional convention question.

The table below shows the last and next constitutional convention question election years:

| State | Interval | Last question on the ballot | Next question on the ballot |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maryland | 20 years | 2010 | 2030 |

See also

- Maryland

- Maryland House of Delegates

- Maryland State Senate

- Governor of Maryland

- Maryland Constitution

External links

- Official Maryland General Assembly Website

- Washington Post: Metro Report: Maryland Legislature

- Info on General Assembly from Maryland Manual Online

- Article III of the Maryland Constitution (Legislative Department)

- The Archives of Maryland, Legislative Records - Proceedings, Acts and Public Documents of the General Assembly

- Wikipedia: Maryland Legislature

Footnotes

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau, "States Ranked by Population," April 2, 2001

- ↑ Maryland State Board of Elections, "2018 Election Calendar," accessed July 6, 2018

- ↑ Maryland State Board of Elections, "2018 Election Calendar," accessed July 6, 2018

- ↑ Patch, "MD Legislature To Adjourn Early, Create Coronavirus Committees," March 15, 2020

- ↑ The Washington Post, "As Md. legislative session nears, uncertainty about Hogan’s agenda," January 10, 2015

- ↑ washingtonpost.com, "10 things to watch in the 2014 Maryland General Assembly session," January 7, 2014

- ↑ Washington Post, "Maryland legislative session begins with bold predictions," January 9, 2013

- ↑ Maryland Department of Legislative Services, "Journal of Proceedings of the Senate of Maryland - 2011 Regular Session - Volume I," accessed February 11, 2021 (Referenced p. iv)

- ↑ Associated Press, "Md. special session anticipated in week of Oct. 17," July 6, 2011

- ↑ Maryland Department of Legislative Services, "Journal of Proceedings of the Senate of Maryland - 2011 Special Session," accessed February 11, 2021

- ↑ Maryland Department of Legislative Services, "Journal of Proceedings of the Senate of Maryland - 2010 Regular Session - Volume I," accessed June 15, 2014 (Referenced p. iv)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 National Association of State Budget Officers, "Budget Processes in the States, Spring 2021," accessed January 24, 2023

- ↑ National Conference of State Legislatures, "Separation of Powers: Executive Veto Powers," accessed January 26, 2024

- ↑ Maryland Secretary of State, "Ballot Question Summaries," accessed January 26, 2024

- ↑ Maryland State Board of Elections, "Official 2020 Presidential General Election results for All State Questions," accessed January 26, 2024

- ↑ Pew Charitable Trusts, "State Work," accessed June 6, 2014

- ↑ Pew Charitable Trusts, "States’ Use of Cost-Benefit Analysis," July 29, 2013

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 U.S. Public Interest Research Group, "Following the Money 2015 Report," accessed April 4, 2016

- ↑ Sunlight Foundation, "Ten Principles for Opening Up Government Information," accessed June 16, 2013

- ↑ National Council of State Legislatures, "Dual employment: regulating public jobs for legislators - 50 state table," January 2015

- ↑ National Council of State Legislatures, "Ethics: personal financial disclosure for state legislators: income requirements," June 2014

- ↑ Maryland Department of Planning, "Redistricting FAQs," accessed June 16, 2011

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau, "2010 Census: Maryland Profile, 2011

- ↑ The Baltimore Sun, "Maryland population grows by 480,000, Census says," December 21, 2010

- ↑ Baltimore Sun, "Redistricting: Mighty Baltimore to lose influence," August 11, 2011

- ↑ WBAL, "Lawmakers To Let O'Malley Redistricting Plan Take Effect Without a Vote," accessed February 23, 2012

- ↑ Baltimore Sun, "Redistricting plan questioned after O'Malley adviser's conviction," December 22, 2011

- ↑ The Baltimore Sun, "Redistricting Map Foes Say They Have Passed First Test," May 31, 2012

- ↑ Southern Maryland Online, "Democratic Lawsuit Challenges GOP Petition Success," July 27, 2012

- ↑ National Conference of State Legislatures, "2024 Legislator Compensation," August 21, 2024

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Gazette.net, "Redrawn lines will lead to court, redistricting expert says," July 15, 2011

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau, "States Ranked by Population," April 2, 2001

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau, "States Ranked by Population," April 2, 2001

- ↑ The Baltimore Sun, "Hogan vetoes Maryland Democrats' paid sick leave bill," May 25, 2017

- ↑ National Conferences of State Legislatures, "Special sessions," May 6, 2009

|

State of Maryland Annapolis (capital) |

|---|---|

| Elections |

What's on my ballot? | Elections in 2025 | How to vote | How to run for office | Ballot measures |

| Government |

Who represents me? | U.S. President | U.S. Congress | Federal courts | State executives | State legislature | State and local courts | Counties | Cities | School districts | Public policy |