Ballot access for presidential candidates

In order to get on the ballot, a candidate for president of the United States must meet a variety of complex, state-specific filing requirements and deadlines. These regulations, known as ballot access laws, determine whether a candidate or party will appear on an election ballot. These laws are set at the state level. A presidential candidate must prepare to meet ballot access requirements well in advance of primaries, caucuses and the general election.

There are three basic methods by which an individual may become a candidate for president of the United States.

- An individual can seek the nomination of a political party. Presidential nominees are selected by delegates at national nominating conventions. Individual states conduct caucuses or primary elections to determine which delegates will be sent to the national convention.[1]

- An individual can run as an independent. Independent presidential candidates typically must petition each state to have their names printed on the general election ballot. For the 2016 presidential contest, it was estimated that an independent candidate would need to collect in excess of 900,000 signatures in order to appear on the general election ballot in every state.[1]

- An individual can run as a write-in candidate. In 35 states, a write-in candidate must file some paperwork in advance of the election. In seven states, write-in voting for presidential candidates is not permitted. The remaining states do not require write-in candidates to file paperwork in advance of the election.[1]

The information presented here applies only to presidential candidates. For additional information about ballot access requirements for state and congressional candidates, see this article.

Election dates and filing deadlines, 2016

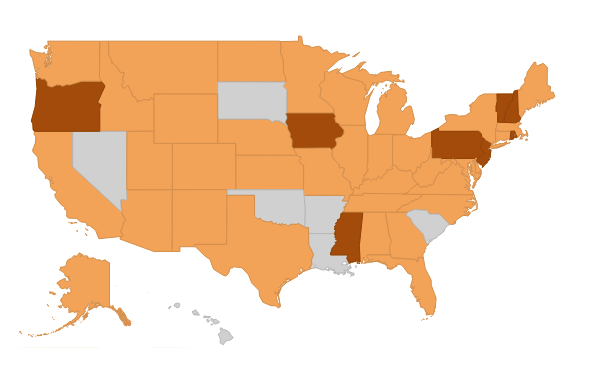

The maps below detail the election dates and candidate filing deadlines for the Democratic and Republican presidential primaries and caucuses in 2016. The states that have earlier deadlines are shaded in darker colors. A table listing the same information can be found below the maps.

Qualifications

Article 2, Section 1, of the United States Constitution sets the following qualifications for the presidency:[2]

| “ | No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President; neither shall any Person be eligible to that Office who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty five Years, and been fourteen Years a Resident within the United States.[3] | ” |

| —United States Constitution | ||

Article 2, Section 4, of the United States Constitution says an individual can be disqualified from the presidency if impeached and convicted:

| “ | The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.[3] | ” |

| —United States Constitution | ||

The 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution says an individual can also be disqualified from the presidency under the following conditions:

| “ | No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.[3] | ” |

| —United States Constitution | ||

Party nomination processes

- See also: Primary election and Caucus

| Hover over the terms below to display definitions. | |

| Ballot access laws | |

| Primary election | |

| Caucus | |

| Delegate | |

A political party formally nominates its presidential candidate at a national nominating convention. At this convention, state delegates select the party's nominee. Prior to the nominating convention, the states conduct presidential preference primaries or caucuses. Generally speaking, only state-recognized parties — such as the Democratic Party and the Republican Party — conduct primaries and caucuses. These elections measure voter preference for the various candidates and help determine which delegates will be sent to the national nominating convention.[1][4][5]

The Democratic National Committee and the Republican National Committee, the governing bodies of the nation's two major parties, establish their own guidelines for the presidential nomination process. State-level affiliates of the parties also have some say in determining rules and provisions in their own states. Individuals interested in learning more about the nomination process should contact the political parties themselves for full details.

Statutory requirements

As noted above, political parties have considerable freedom to determine the methods by which they nominate presidential candidates. In those states that conduct presidential preference primaries, there are usually some statutory candidate filing requirements, but these vary considerably from state to state. In most states that conduct primaries, a candidate may petition for placement on the primary ballot. In some states, elections officials or party leaders select candidates to appear on the ballot; candidates selected in this manner are not usually required to file additional paperwork. In other states, a candidate may have to pay a filing fee (to the state, to the party, or both) in order to have his or her name printed on the ballot.

The table below summarizes general statutory filing procedures for a candidate seeking the nomination of his or her party. Please note that this information is not exhaustive. Specific filing requirements can vary by party and by state. For more information, contact the appropriate state-level party.

| Filing requirements for partisan candidates, 2016 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | Primary or caucus | Filing method | Details |

| Alabama | Primary | Petition and filing fee | The candidate must file a petition containing at least 500 signatures. In addition, the candidate must pay a filing fee, which is set by the party. |

| Alaska | Caucus | N/A | N/A |

| Arizona | Primary | Petition or proof of ballot placement in other states | The candidate must file a petition containing at least 500 signatures. Alternatively, the candidate must prove that he or she will appear on the ballot in at least two other states. |

| Arkansas | Primary | Filing fee | The candidate must file with his or her political party. The candidate may be required to pay a filing fee, which is set by the party. Upon filing with the party, the candidate must submit a party certificate to the secretary of state. |

| California | Primary | Petition | A candidate must petition for placement on the primary ballot. Signature requirements vary from party to party. |

| Colorado | Caucus | N/A | N/A |

| Connecticut | Primary | Petition or selection by elections officials | The secretary of state can order that a candidate's name be printed on the primary ballot. Alternatively, the candidate must file a petition containing signatures equaling at least 1 percent of the total number of enrolled members in the candidate's party in the state. |

| Delaware | Primary | Petition | The candidate must file a petition containing signatures from at least 500 voters belonging to the same party as the candidate. |

| Florida | Primary | Selection by party officials | The parties submit lists of their primary candidates for placement on the ballot. |

| Georgia | Primary | Selection by party officials | The parties submit lists of their primary candidates for placement on the ballot. |

| Hawaii | Caucus | N/A | N/A |

| Idaho | Both | Filing fee | A candidate must pay a $1,000 filing fee in order to have his or her name printed on the primary ballot. |

| Illinois | Primary | Petition | The candidate must file a petition containing between 3,000 and 5,000 signatures. Only members of the candidate's party can sign the petition. |

| Indiana | Primary | Petition | The candidate must file a petition containing at least 4,500 signatures; at least 500 signatures must come from each of Indiana's congressional districts. |

| Iowa | Caucus | N/A | N/A |

| Kansas | Caucus | N/A | N/A |

| Kentucky | Both | Petition or selection by elections officials, as well as a filing fee | The Kentucky State Board of Elections nominates candidates to appear on the primary ballot. Alternatively, a candidate can petition for placement on the primary ballot. This petition must contain at least 5,000 signatures. All presidential primary candidates are liable for a $1,000 filing fee. |

| Louisiana | Primary | Petition or filing fee | The candidate must pay a filing fee of $750, plus "any additional fee imposed by a political party state central committee." Alternatively, a candidate may petition for placement on the primary ballot. This petition must contain at least 6,000 signatures; only voters belonging to the same party as the candidate can sign the petition. |

| Maine | Caucus | N/A | N/A |

| Maryland | Primary | Petition or selection by elections officials | The secretary of state determines which candidates appear on the primary ballot. Alternatively, a candidate can petition for placement on the primary ballot. This petition must contain at least 400 signatures. |

| Massachusetts | Primary | Petition, selection by elections officials, or selection by party officials | A candidate can petition for placement on the primary ballot. This petition must contain at least 2,500 signatures. Alternatively, the secretary of state and party officials can select names to appear on the primary balllot. |

| Michigan | Primary | Petition, selection by elections officials, or selection by party officials | A candidate can petition for placement on the primary ballot. This petition must contain signatures equaling at least one-half of 1 percent "of the total votes cast in the state at the previous presidential election for the presidential candidate of the political party for which the individual is seeking this nomination." Alternatively, the secretary of state and party officials can select names to appear on the primary ballot. |

| Minnesota | Caucus | N/A | N/A |

| Mississippi | Primary | Petition or selection by elections officials | The secretary of state determines which candidates appear on the primary ballot. Alternatively, a candidate can petition for ballot placement. This petition must contain at least 500 signatures. |

| Missouri | Primary | Petition or filing fee | A candidate must pay a $1,000 filing fee to his or her party in order to appear on the primary ballot. Alternatively, a candidate can petition for ballot placement. This petition must contain at least 5,000 signatures. |

| Montana | Primary | Petition | A candidate must submit a petition containing at least 500 signatures in order to have his or her name printed on the primary ballot. |

| Nebraska | Both | Petition or selection by elections officials | The secretary of state determines which candidates appear on the primary ballot. Alternatively, a candidate can petition for ballot placement. The petition must contain 100 signatures from each of the state's congressional districts; only voters belonging to the same party as the candidate can sign the petition. |

| Nevada | Caucus | N/A | N/A |

| New Hampshire | Primary | Filing fee | A candidate must pay a $1,000 filing fee in order to have his or her named printed on the primary ballot. |

| New Jersey | Primary | Petition | A candidate must submit a petition containing at least 1,000 signatures in order to have his or her name printed on the primary ballot; only voters belonging to the same party as the candidate can sign the petition. |

| New Mexico | Primary | Petition | A special committee determines which candidates appear on the primary ballot. Alternatively, a candidate can petition for placement on the primary ballot. The petition must contain signatures equaling at least 2 percent of the total votes cast for president in each of the state's congressional districts in the last election. |

| New York | Primary | N/A[6] | N/A[6] |

| North Carolina | Primary | Petition, selection by elections officials, or selection by party officials | Party leaders and elections officials select names to appear on the primary ballot. Alternatively, a candidate can petition for placement on the ballot. The petition must contain 10,000 signatures; only voters belonging to the same party as the candidate can sign the petition. |

| North Dakota | Caucus | N/A | N/A |

| Ohio | Primary | N/A[6] | N/A[6] |

| Oklahoma | Primary | Petition or filing fee | A candidate can petition for placement on the primary ballot. This petition must be signed by 1 percent of the registered voters in each congressional district, or 1,000 registered voters in each congressional district, whichever is less. Alternatively, the candidate can pay a $2,500 filing fee. |

| Oregon | Primary | Petition or selection by elections officials | The secretary of state selects names to appear on the primary ballot. Alternatively, a candidate can petition for ballot placement. The petition must be signed by at least 1,000 voters from each of the state's congressional districts; only voters belonging to the same party as the candidate can sign the petition. |

| Pennsylvania | Primary | Petition and filing fee | A candidate must submit a petition containing 2,000 signatures. The candidate must also pay a $200 filing fee. |

| Rhode Island | Primary | Petition | The candidate must submit a petition containing at least 1,000 signatures. |

| South Carolina | Primary | Method varies by party | Ballot access methods vary by party. |

| South Dakota | Primary | Notice of intent and selection by party officials | A primary candidate must file a notice of intent in order to have his or her name printed on the primary ballot. A party participating in the primary must "certify the candidate names or the delegates and alternate slates which are to be listed on the primary ballot" to the secretary of state. |

| Tennessee | Primary | Petition or selection by elections officials | The secretary of state determines which candidates appear on the primary ballot. Alternatively, a candidate can petition for ballot placement. This petition must be signed by at least 2,500 registered voters. |

| Texas | Primary | Method varies by party | Ballot access methods vary by party. |

| Utah | Caucus | N/A | N/A |

| Vermont | Primary | Petition and filing fee | A candidate must submit a petition and pay a $2,000 filing fee. The petition must contain at least 1,000 signatures. |

| Virginia | Primary | Petition | A candidate must submit a petition containing at least 5,000 signatures, with at least 200 signatures from each of the state's congressional districts. |

| Washington | Both | Petition or selection by elections officials | The secretary of state determines which candidates appear on the primary ballot. Alternatively, a candidate can submit a petition containing at least 1,000 signatures; only voters belonging to the same party as the candidate can sign the petition. |

| Washington, D.C. | Both | Petition | The candidate must petition for placement on the primary ballot. The petition must contain signatures equaling at least 1 percent of the district's qualified voters, or 1,000 signatures, whichever is less. |

| West Virginia | Primary | Petition or filing fee | The candidate must pay a $2,500 filing fee in order to have his or her name printed on the primary ballot. Alternatively, a candidate can petition for ballot placement. This petition must contain at least 10,000 signatures (four signatures for every dollar of the filing fee). |

| Wisconsin | Primary | Petition or selection by elections officials | The Presidential Preference Selection Committee determines which names appear on the primary ballot. Alternatively, a candidate can petition for ballot placement. This petition must contain at least 1,000 signatures from each of the state's congressional districts. |

| Wyoming | Caucus | N/A | N/A |

| Note: Because caucuses are administered by political parties themselves with minimal involvement from the state, there are typically no formal legal filing requirements for candidates in these contests. Source: This information was compiled by Ballotpedia staff in September 2015. For specific references to state statutes, see the appropriate state page. | |||

Requirements for independents

Generally speaking, an independent presidential candidate must petition for placement on the general election ballot in all 50 states, as well as Washington, D.C. A handful of states may allow an independent candidate to pay a filing fee in lieu of submitting a petition. The methods for calculating how many signatures are required vary considerably from state to state, as do the actual signature requirements. For instance, some states establish a flat signature requirement. Other states calculate signature requirements as percentages of voter registration or votes cast for a given office.

In order to access the ballot nationwide, it is estimated that an independent presidential candidate in 2016 would need to collect more than 900,000 signatures. This amounts to approximately 0.29 percent of the nation's population. California is expected to require independent candidates to collect 178,039 signatures, more than any other state. Tennessee is expected to require 275 signatures, fewer than any other state.

In 2016, Oklahoma is expected to require independent candidates to collect 40,047 signatures in order to have their names printed on the general election ballot. This equals approximately 1.04 percent of the state's total population, a greater share than in any other state. The map below compares signature requirements by state, both as raw numbers and as percentages of state population. A lighter shade indicates a lower total signature requirement as a percentage of state population while a darker shade indicates a higher signature requirement. It should be noted that other variables factor in this process; for instance, some states require candidates to collect a certain number of signatures from each congressional district.

Signature requirements

The table below provides the formula used for determining the number of required signatures, the estimated number of signatures required, the number of required signatures as a percentage of state population, and the 2016 filing deadline. Official signature requirements are published by state elections administrators; the numbers presented here are estimates based on the most recent data available as of November 2015.

| Petition signature requirements for independent presidential candidates, 2016 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Formula | Example of signatures needed | Example as a percentage of state population | Filing deadline |

| Alabama | 5,000 | 5,000 | 0.10% | 8/18/2016 |

| Alaska | 1% of the total number of state voters who cast ballots for president in the most recent election | 3,005 | 0.41% | 8/10/2016 |

| Arizona | 3% of all registered voters who are not affiliated with a qualified political party | 36,000 | 0.54% | 9/9/2016 |

| Arkansas | 1,000 | 1,000 | 0.03% | 8/1/2016 |

| California | 1% of the total number of registered voters in the state at the time of the close of registration prior to the preceding general election | 178,039 | 0.46% | 8/12/2016 |

| Colorado | 5,000 | 5,000 | 0.09% | 8/10/2016 |

| Connecticut | 1% of the total vote cast for president in the most recent election, or 7,500, whichever is less | 7,500 | 0.21% | 8/10/2016 |

| Delaware | 1% of the total number of registered voters in the state | 6,500 | 0.70% | 7/15/2016 |

| Florida | 1% of the total number of registered voters in the state | 119,316 | 0.61% | 7/15/2016 |

| Georgia | 1% of the total number of registered and eligible voters in the most recent presidential election | 49,336 | 0.49% | 7/12/2016 |

| Hawaii | 1% of the total number of votes cast in the state for president in the most recent election | 4,347 | 0.31% | 8/10/2016 |

| Idaho | 1,000 | 1,000 | 0.06% | 8/24/2016 |

| Illinois | 1% of the total number of voters in the most recent statewide general election, or 25,000, whichever is less | 25,000 | 0.19% | 6/27/2016 |

| Indiana | 2% of the total vote cast for secretary of state in the most recent election | 26,700 | 0.41% | 6/30/2016 |

| Iowa | 1,500 eligible voters from at least 10 of the state's counties | 1,500 | 0.05% | 8/19/2016 |

| Kansas | 5,000 | 5,000 | 0.17% | 8/1/2016 |

| Kentucky | 5,000 | 5,000 | 0.11% | 9/9/2016 |

| Louisiana | 5,000 | 5,000 | 0.11% | 8/19/2016 |

| Maine | Between 4,000 and 6,000 | 4,000 | 0.30% | 8/1/2016 |

| Maryland | 1% of the total number of registered state voters | 38,000 | 0.64% | 8/1/2016 |

| Massachusetts | 10,000 | 10,000 | 0.15% | 8/2/2016 |

| Michigan | 30,000 | 30,000 | 0.30% | 7/21/2016 |

| Minnesota | 2,000 | 2,000 | 0.04% | 8/23/2016 |

| Mississippi | 1,000 | 1,000 | 0.03% | 9/9/2016 |

| Missouri | 10,000 | 10,000 | 0.17% | 7/25/2016 |

| Montana | 5% of the total votes cast for the successful candidate for governor in the last election, or 5,000, whichever is less | 5,000 | 0.49% | 8/17/2016 |

| Nebraska | 2,500 registered voters who did not vote in any party's primary | 2,500 | 0.13% | 8/1/2016 |

| Nevada | 1% of the total number of votes cast for all representatives in Congress in the last election | 5,431 | 0.19% | 7/8/2016 |

| New Hampshire | 3,000 voters, with at least 1,500 from each congressional district | 3,000 | 0.23% | 8/10/2016 |

| New Jersey | 800 | 800 | 0.01% | 8/1/2016 |

| New Mexico | 3% of the total votes cast for governor in the last general election | 15,388 | 0.74% | 6/30/2016 |

| New York | 15,000, with at least 100 from each of the state's congressional districts | 15,000 | 0.08% | 8/23/2016 |

| North Carolina | 2% of the total votes cast for governor in the previous general election | 89,366 | 0.91% | 6/9/2016 |

| North Dakota | 4,000 | 4,000 | 0.55% | 9/5/2016 |

| Ohio | 5,000 | 5,000 | 0.04% | 8/10/2016 |

| Oklahoma | 3% of the total votes cast in the last general election for president | 40,047 | 1.04% | 7/15/2016 |

| Oregon | 1% of the total votes cast in the last general election for president | 17,893 | 0.46% | 8/30/2016 |

| Pennsylvania | 2% of the largest entire vote cast for any elected candidate in the state at the last preceding election at which statewide candidates were voted for" | 25,000 | 0.20% | 8/1/2016 |

| Rhode Island | 1,000 | 1,000 | 0.10% | 9/9/2016 |

| South Carolina | 5% of registered voters up to 10,000 | 10,000 | 0.21% | 7/15/2016 |

| South Dakota | 1% of the combined vote for governor in the last election | 2,775 | 0.33% | 4/26/2016 |

| Tennessee | 25 votes per state elector (275 total) | 275 | 0.00% | 8/18/2016 |

| Texas | 1% of the total votes cast for all candidates in the previous presidential election | 79,939 | 0.30% | 5/9/2016 |

| Utah | 1,000 | 1,000 | 0.03% | 8/15/2016 |

| Vermont | 1,000 | 1,000 | 0.16% | 8/1/2016 |

| Virginia | 5,000 registered voters, with at least 200 from each congressional district | 5,000 | 0.06% | 8/26/2016 |

| Washington | 1,000 | 1,000 | 0.01% | 7/23/2016 |

| Washington, D.C. | 1% of the district's qualified voters | 4,600 | 0.71% | 8/10/2016 |

| West Virginia | 1% of the total votes cast in the state for president in the most recent election | 6,705 | 0.36% | 8/1/2016 |

| Wisconsin | Between 2,000 and 4,000 | 2,000 | 0.03% | 8/2/2016 |

| Wyoming | 2% of the total number of votes cast for United States Representative in the most recent general election | 3,302 | 0.57% | 8/30/2016 |

| TOTALS | 926,263 | 0.29% | N/A | |

| Note: Two states (Colorado and Louisiana) allow independent candidates to pay filing fees in lieu of submitting petitions. Sources: This information was compiled by Ballotpedia staff in November 2015. These figures were verified against those published by Richard Winger in the October 2015 print edition of Ballot Access News. | ||||

Requirements for write-in candidates

Although a write-in candidate is not entitled to ballot placement, he or she may still be required to file paperwork in order to have his or her votes tallied (or to be eligible to serve should the candidate be elected). In 35 states, a write-in presidential candidate must file some paperwork in advance of an election. In seven states, write-in voting for presidential candidates is not permitted. The remaining states do not require presidential write-in candidates to file special paperwork before the election. See the map below for further details.

Legend: Filing required

in advance No filing requirements Write-in votes not permitted |

"Sore loser" laws

Some states bar candidates who sought, but failed, to secure the nomination of a political party from running as independents in the general election. Ballot access expert Richard Winger has noted that, generally speaking, "sore loser laws have been construed not to apply to presidential primaries." In August 2015, Winger compiled a list of precedents supporting this interpretation. According to Winger, 45 states have sore loser laws on the books, but in 43 of these states the laws do not seem to apply to presidential candidates. Sore loser laws apply to presidential candidates in only two states: South Dakota and Texas. See this article for further details.[7][8][9]

Historical information

According to ballot access expert Richard Winger, between 1892 and 2012 there were 401 instances in which a state required an independent or minor party candidate to collect more than 5,000 signatures in order to appear on the general election ballot. Winger said, "Every state has procedures for independent presidential candidates [as well] as procedures for newly-qualifying parties. ... Throughout U.S. history, the presidential nominees of unqualified parties have frequently used the independent candidate procedure instead of the new party procedure, if the independent procedure was easier. The reverse is also true." See this article for state-by-state details.[7]

Campaign finance requirements

The Federal Election Commission (FEC) is the only agency authorized to regulate the financing of presidential and other federal campaigns (i.e., campaigns for the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives). The states cannot impose additional requirements on federal candidates. Federal law requires all presidential candidates to file a statement of candidacy within 15 days of receiving contributions or making expenditures that exceed $5,000. The statement of candidacy is the only federally mandated ballot access requirement for presidential candidates; all other ballot access procedures are mandated at the state level. The candidacy statement authorizes "a principal campaign committee to raise and spend funds" on behalf of the candidate. Within 10 days of filing the candidacy statement, the committee must file a statement of organization with the FEC. In addition, federal law establishes contribution limits for presidential candidates. These limits are detailed in the table below. The uppermost row indicates the recipient type; the leftmost column indicates the donor type.[10][11]

| Candidate committees | Political action committees | State and district party committees | National party committees | Additional national party committee accounts | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | $3,300 per election | $5,000 per year | $10,000 per year (combined) | $41,300 per year | $123,900 per account, per year |

| Candidate committee | $2,000 per election | $5,000 per year | Unlimited transfers | Unlimited transfers | N/A |

| Multicandidate political action committee | $5,000 per election | $5,000 per year | $5,000 per year (combined) | $15,000 per year | $45,000 per account, per year |

| Other political action committee | $3,300 per election | $5,000 per year | $10,000 per year (combined) | $41,300 per year | $123,900 per account, per year |

| State and district party committee | $5,000 per election | $5,000 per year | Unlimited transfers | Unlimited transfers | N/A |

| National party committee | $5,000 per election | $5,000 per year | Unlimited transfers | Unlimited transfers | N/A |

| Note: Contribution limits apply separately to primary and general elections. For example, an individual could contribute $3,300 to a candidate committee for the primary and another $3,300 to the same candidate committee for the general election. Source: Federal Election Commission, "Contribution limits," accessed May 8, 2023 |

|||||

Presidential candidate committees are required to file regular campaign finance reports disclosing "all of their receipts and disbursements" either quarterly or monthly. Committees may choose which filing schedule to follow, but they must notify the FEC in writing and "may change their filing frequency no more than once per calendar year."[12]

For contribution limits from previous years, click "[Show more]" below.

| Federal contribution limits, 2019-2020 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate committees | Political action committees | State and district party committees | National party committees | Additional national party committee accounts | |

| Individual | $2,800 per election | $5,000 per year | $10,000 per year (combined) | $33,500 per year | $106,500 per account, per year |

| Candidate committee | $2,000 per election | $5,000 per year | Unlimited transfers | Unlimited transfers | N/A |

| Multicandidate political action committee | $5,000 per election | $5,000 per year | $5,000 per year (combined) | $15,000 per year | $45,000 per account, per year |

| Other political action committee | $2,800 per election | $5,000 per year | $10,000 per year (combined) | $35,500 per year | $106,500 per account, per year |

| State and district party committee | $5,000 per election | $5,000 per year | Unlimited transfers | Unlimited transfers | N/A |

| National party committee | $5,000 per election | $5,000 per year | Unlimited transfers | Unlimited transfers | N/A |

| Note: Contribution limits apply separately to primary and general elections. For example, an individual could contribute $2,800 to a candidate committee for the primary and another $2,800 to the same candidate committee for the general election. Source: Federal Election Commission, "Contribution limits," accessed August 8, 2019 | |||||

| Federal contribution limits, 2015-2016 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate committees | Political action committees | State and district party committees | National party committees | Additional national party committee accounts | |

| Individual | $2,700 per election | $5,000 per year | $10,000 per year (combined) | $33,400 per year | $100,200 per account, per year |

| Candidate committee | $2,000 per election | $5,000 per year | Unlimited transfers | Unlimited transfers | N/A |

| Multicandidate political action committee | $5,000 per election | $5,000 per year | $5,000 per year (combined) | $15,000 per year | $45,000 per account, per year |

| Other political action committee | $2,700 per election | $5,000 per year | $10,000 per year (combined) | $33,400 per year | $100,200 per account, per year |

| State and district party committee | $5,000 per election | $5,000 per year | Unlimited transfers | Unlimited transfers | N/A |

| National party committee | $5,000 per election | $5,000 per year | Unlimited transfers | Unlimited transfers | N/A |

| Note: Contribution limits apply separately to primary and general elections. For example, an individual could contribute $2,700 to a candidate committee for the primary and another $2,700 to the same candidate committee for the general election. Source: Federal Election Commission, "The FEC and Federal Campaign Finance Law," updated January 2015 | |||||

Notable independent and third party candidacies

Ross Perot, 1992

On February 20, 1992, in a televised interview with Larry King, Texas businessman Ross Perot announced that he would seek the presidency as an independent candidate if his supporters took the initiative to get his name on the ballot in all 50 states. According to MSNBC, "a national grassroots mobilization ensued and Perot moved up in the polls." An ABC News/Washington Post poll conducted in early June 1992 found Perot leading both incumbent George H.W. Bush (R) and Bill Clinton (D).[13][14][15]

Perot's support waned over the course of the summer, however, and in July he announced his withdrawal from the race. In October 1992, Perot announced his re-entry into the presidential race. He participated in the presidential debates that fall and experienced a surge of support in the polls leading up to Election Day. Ultimately, Perot won 19.7 million votes, accounting for 19 percent of the nationwide popular vote. Perot won no electoral votes, however, and Clinton was elected president. Perot appeared on the ballot in all 50 states.[13][14][15]

Speculation surrounding Donald Trump, 2015

On August 6, 2015, the first Republican presidential primary debate of the 2016 election season took place in Cleveland, Ohio. At the beginning of the debate, moderate Bret Baier asked candidates to raise their hands if they were unwilling to pledge not run as third party candidates in the fall, should they fail to win the Republican nomination. Donald Trump, the frontrunner at the time of the debate, was the only candidate to raise his hand. Following the debate, Trump continued to refuse to rule out a third party or independent run if he failed to secure the party's nomination. However, on September 3, 2015, Trump signed a party loyalty pledge affirming that he would endorse the ultimate Republican nominee and forgo an independent or third party run. Describing his bid for the 2016 Republican nomination, Trump said, "We have our heart in it. We have our soul in it."[16][17]

According to The Wall Street Journal, "GOP analysts said they had never heard of such a pledge being used in modern elections, and questioned if it would be binding or survive a legal challenge." Republican Party operative Peter Wehner said, "If they [at the RNC] think it's honestly going to keep [Trump] from running for a third-party bid, they are delirious. Donald Trump does what is in the interest of Donald Trump. He has no loyalty to the Republican Party."[16][17]

Notable court cases

Williams v. Rhodes

- See also: Williams v. Rhodes

The American Independent Party and the Socialist Labor Party sought ballot access in Ohio for the 1968 presidential election. At the time, Ohio state law required the candidate's political party to obtain voter signatures totaling 15 percent of the number of ballots cast in the preceding election for governor. The American Independent Party obtained the required number of signatures but did not file its petition prior to the stated deadline. The Socialist Labor Party did not collect the requisite signatures. Consequently, both parties were denied placement on the ballot. The two parties filed separate suits in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio against a variety of state officials, including then-Governor James Rhodes.[18][19]

On October 15, 1968, in a 6-3 decision, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Williams v. Rhodes that the state laws in dispute were "invidiously discriminatory" and violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because they gave "the two old, established parties a decided advantage over new parties." The court also ruled that the challenged laws restricted the right of individuals "to associate for the advancement of political beliefs" and "to cast their votes effectively." The court further ruled that Ohio showed no "compelling interest" to justify these restrictive practices and ordered the state to place the American Independent Party's candidates for the presidency and vice-presidency on the ballot. The court did not require the state to place the Socialist Labor Party's candidates for the same offices on the ballot.[18][19]

Anderson v. Celebrezze

- See also: Anderson v. Celebrezze

An Ohio statute required independent presidential candidates to file statements of candidacy and nominating petitions in March in order to qualify to appear on the general election ballot in November. Independent candidate John Anderson announced his candidacy for President in April 1980 and all requisite paperwork was submitted on May 16, 1980. The Ohio Secretary of State, Anthony J. Celebrezze, refused to accept the documents.[20][21]

Anderson and his supporters filed an action challenging the constitutionality of the aforementioned statute on May 19, 1980, in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio. The district court ruled in Anderson's favor and ordered Celebrezze to place Anderson's name on the ballot. Celebrezze appealed the decision to the United States Court of Appeals, which ultimately overturned the district court's ruling (the election took place while this appeal was pending).[20][21]

On April 19, 1983, in a 5-4 decision, the United States Supreme Court reversed the appeals court's ruling, maintaining that Ohio's early filing deadline indeed violated the voting and associational rights of Anderson's supporters.[20][21]

Recent news

The link below is to the most recent stories in a Google news search for the terms President ballot access. These results are automatically generated from Google. Ballotpedia does not curate or endorse these articles.

See also

- Presidential election, 2016

- Ballot access for major and minor party candidates

- Other ballot access lawsuits:

- Bullock v. Carter (1972)

- Lubin v. Panish (1974)

- Storer v. Brown (1974)

- Illinois State Board of Elections v. Socialist Workers Party (1979)

- Norman v. Reed (1992)

- U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton (1995)

External links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Vote Smart, "Government 101: United States Presidential Primary," accessed August 15, 2015 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "votesmart" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ The Constitution of the United States of America, "Article 2, Section 1," accessed August 3, 2015

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ The Washington Post, "Everything you need to know about how the presidential primary works," May 12, 2015

- ↑ FactCheck.org, "Caucus vs. Primary," February 3, 2020

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 More information about this state's filing processes will be added when it becomes available.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 This information comes from research conducted by Richard Winger, publisher and editor of Ballot Access News.

- ↑ The Georgetown Law Journal, "Sore Lower Laws and Democratic Contestation," accessed August 13, 2015

- ↑ CNN, "Trump 3rd party run would face 'sore loser' laws," August 13, 2015

- ↑ Federal Election Commission, "The FEC and Federal Campaign Finance Law," updated January 2015

- ↑ Federal Election Commission, "Quick Answers to Candidate Questions," accessed August 13, 2015

- ↑ Federal Election Commission, "2016 Reporting Dates," accessed June 17, 2022

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 MSNBC, "Ross Perot myth reborn amid rumors of third-party Trump candidacy," July 24, 2015

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 PBS, "The Election of 1992," accessed November 6, 2015

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Federal Election Commission, "Federal Elections 92," accessed November 6, 2015

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 The Wall Street Journal, "Donald Trump Swears Off Third-Party Run," September 3, 2015

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 The Guardian, "Donald Trump signs pledge not to run as independent," September 3, 2015

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Justia.com, "Williams v. Rhodes - 393 U.S. 23 (1968)," accessed December 26, 2013

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Oyez - U.S. Supreme Court Media - IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law, "Williams v. Rhodes," accessed December 26, 2013

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Justia.com, "Anderson v. Celebrezze - 460 U.S. 780 (1983)," accessed December 26, 2013

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Oyez Project - U.S. Supreme Court Media - IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law, "Anderson v. Celebrezze," accessed December 26, 2013

| |||||||||||||||||||